The artist’s work is characterised by a sense of mystery, maybe even nonexistence

The work of Olga Balema is a satisfying defiance. She maintains a fluid approach to every aspect of her art: titles, forms, expectations and materials, which are occasionally actual fluids. Most often you can find her work resting on the ground, slumped or flat, and settling into the architecture.

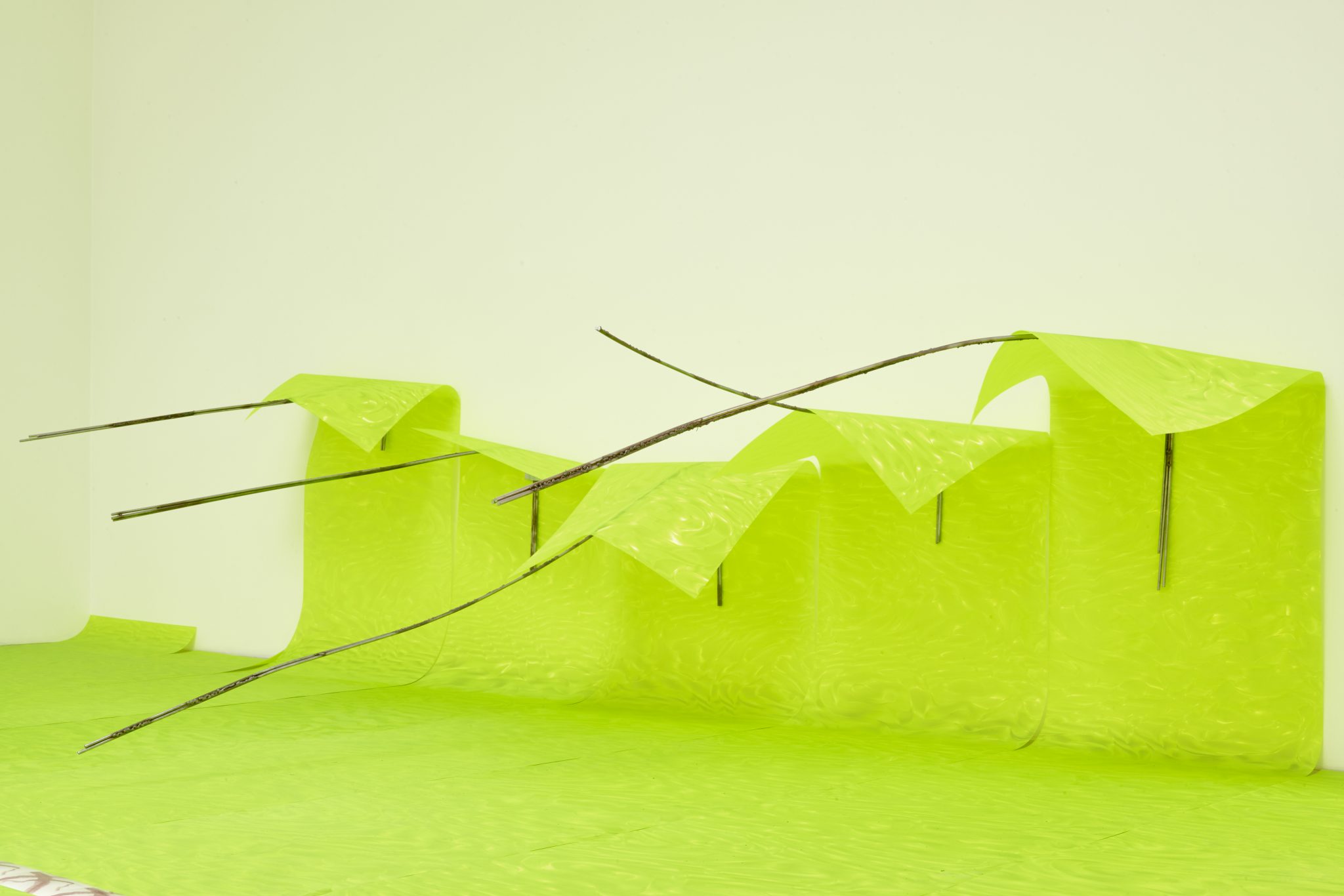

Her recent show Formulas, at Croy Nielsen in Vienna, is a collection of tilelike works, placed on the floor, where they appear to have been broken, then reassembled into elegantly inelegant collage. Her work brain damage (2019) is an installation of sundry spindly threads, stretched at ankle level: a patternless and beguiling web. Another work, Motherfucker (2016), exhibited at the Baltic Triennial in 2018, features sagging breasts affixed to crudely painted ripped maps. (Balema was born in Ukraine, in 1984, and moved to the United States while a teenager.)

For me, Balema’s works have always been characterised by mystery, especially her ongoing series of clear acrylic sculptures. Almost entirely transparent, they rest quietly between the wall and floor, without any interest in announcing their form. Looked at from a certain angle, in a certain light, they would not appear to exist at all.

This translucence is often accented by Balema’s modest installations and bare context. Many of her works are untitled, and in the past she has not been particularly vocal about her work, doing no interviews and making few written statements. But in line with her resistance to consistency, other work carries elaborate titles (eg, Manifestations of our own wickedness and future idiocy, 2017), and at times in the interview below she even responded loquaciously.

Initially when I reached out to Balema about an interview, she turned me down. But eventually we began to speak: first over the phone, then in a series of email exchanges. During this time, she was busy, intermittently sick and installing multiple shows around the world. Our exchange occurred over three seasons.

A Process of No Process

Ross Simonini You said you were late to our conversation last week because you were installing video chat software. Did you manage to avoid video during the pandemic?

Olga Balema I had to install it on my phone, my computer doesn’t have the right headphone jack. But yes, I was not zooming much during the pandemic.

RS Do you use your computer much for your art?

OB Some email. I write on the computer.

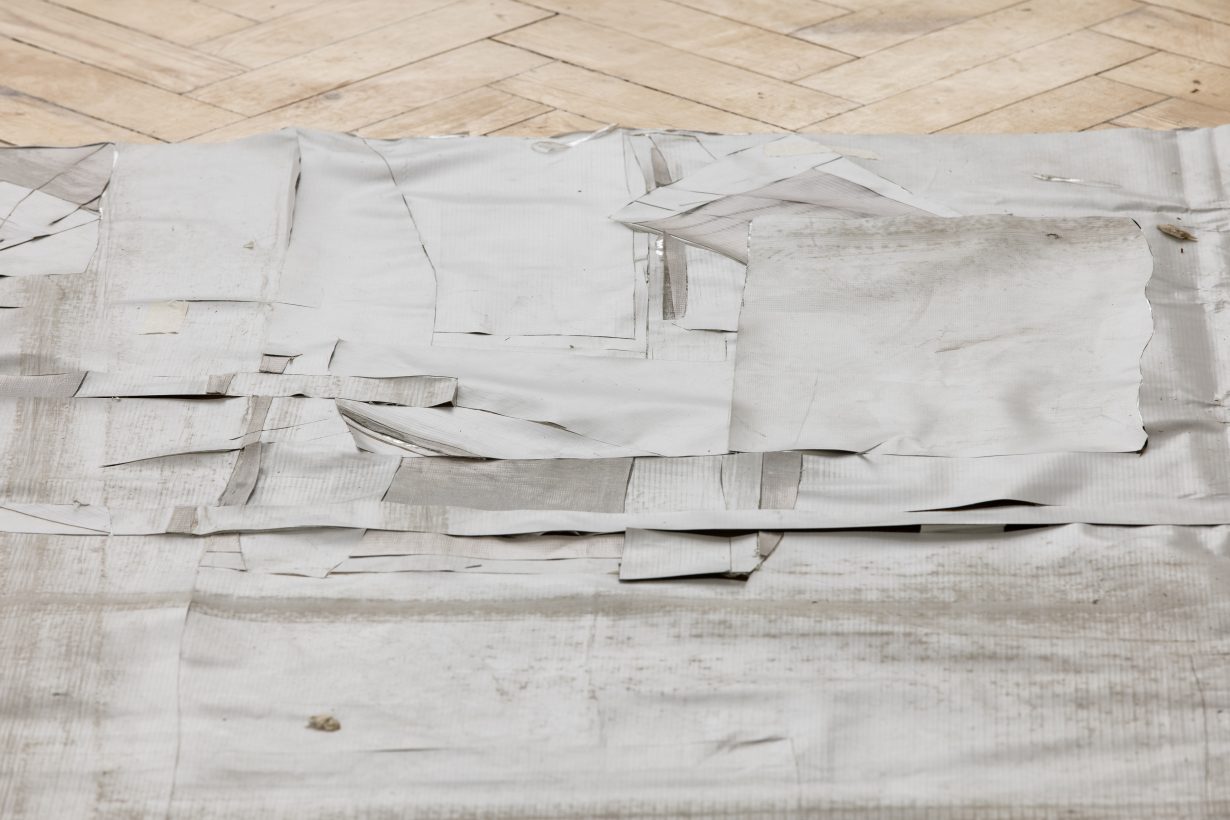

RS Your work Computer (2021), a vast floor collage, somehow led me to assume that you weren’t much of a computer person.

OB I’m not anti, I just don’t really get excited for new technology and try to keep the same devices for as long as I can. I did use a computer to make that work, an old, kind of dirty computer.

RS That title does a lot of work for the piece. Are you careful about titles?

OB Yes. There were a lot of titles swirling around in my mind. And Computer seemed like a nice followup to brain damage. I usually come up with titles during the making of a piece, or after, which is why a lot of things are not titled. If I’m struggling too much, I just leave it untitled. I feel like if I do have a title, I want it to add something to the piece. Computer added a sense of humour that maybe would have been lacking otherwise.

RS What kind of writing are you doing on the computer?

OB Lectures, job applications, grant applications, interviews, press releases. Descriptions of my work for myself and the public. Emails.

RS You mentioned interviews. Have you done others?

OB This is my first ‘real’ interview. But I have done some fake interviews with myself. There is also a conversation I once did with another artist.

RS Do you read about art or artists?

OB Yes, sporadically. Recently I read a Duchamp biography I found on the street in my neighbourhood. Since I’m not moving around as much, I’m trying to buy more books. Reading about other artists can be really inspiring, but it’s also a double-edged sword, because you can end up getting swept up in ideas that have nothing to do with you. Getting hijacked for a second. For example, I did a lecture on the artist Maria Nordman at Dia [Art Foundation, New York]. I was supposed to deliver it in April 2020, so I was doing my research for it in the month before that. Then the pandemic hit and I put it aside and did not think about it for another year. In the meantime I was working on Computer and I was noticing that I had some ideas in my head about it, some concerns that even though related to my past work somehow sat weird. Thoughts about how the audience would almost be finishing the work by wearing it out through movement, that without the audience the work does not really exist. Which partially came from working with a public institution and becoming more aware of how the audience in a way bears a lot of responsibility for its longevity and continued existence. But also in combination with other aspects of the piece, like bringing the piece outside and frottaging the sidewalks in New York. Here I recognised echoes of Nordman’s ideas, especially once I took up preparing the lecture again. It was an instance of not intentionally taking someone else’s work as a reference point, but the idea operating in a deep background.

RS Does social conversation feel laboured for you?

OB I mean… I don’t think I would be described by most people as someone who loves to talk.

RS You sound like someone who doesn’t think in language.

OB I would say that, but when I observe myself, I realise there is no outside of language for me, there is always a lot of language going on in my head, even if it’s nonlinear or incoherent. It shapes how I see.

RS Do you think with your hands?

OB I think with everything: my hands, my brain, my eyes. I can’t say that I only think with one part of my body. A lot of the work happens through association or a kind of visual or textural rhyming in the studio. Physically making things does help in that process. I can’t say that I have a set process of how I do things. Sometimes I come up with something I want to do in my head, and then I try to do it and then it kind of doesn’t work out and I go from there. Or it does work out and then it’s there. Or I abandon it. So it’s a process of no process.

RS Are you resistant to pinning down your process?

OB I’m just trying to be honest. A lot also depends on circumstance and factors outside of my control, like the aesthetics of the places I am showing, shipping constraints, etc.

RS Do you purposely avoid repetition?

OB I used to. There was a lot I wanted to try, and I made this resolution that I would keep my practice very open, make each body of work different from the previous. I found a lot of pleasure and energy in not being consistent, or maybe in trying to figure out a consistency that was more of a feeling than a set of visual attributes. Also I thought it was important that the work was difficult and uncomfortable to absorb. So I really made an effort towards this. Now I am making an effort to stay in the same register a bit more.

RS And why do you want that?

OB I think the shift has been gradual and more internal. I was becoming overwhelmed with the amount of work I was doing and exhausted from the adrenaline rush of constantly trying to do something different and letting too many ideas in. The work became more reduced and quieter because I hit a point at which I was mentally unable to do things like going into the metal workshop and facing the fumes and dust. Also, practically, in New York it’s a true feat to have access to production facilities, especially if you want to do the work yourself and can’t pay a lot of money. So I think it’s partially an adaptation to moving to a very expensive, visually stimulating, loud, crowded city and a response to a need to feel more grounded. That said, ‘same register’ doesn’t mean repetition. I’m still searching for things. It’s important for me that the work feels alive.

RS Have you felt much resistance to that kind of experimental approach?

OB No, not too much from the people I work with. I established this way of working early on as part of my practice, so I assume the people who would resist just did not approach me.

RS Your most recent work at Barbara Weiss in Berlin is working with the same materials and gestures as brain damage. What does that kind of recapitulation do for you?

OB The works at Barbara Weiss were ones I made in 2019 and did not install. So I was engaging with the same body of work, rather than repeating.

RS Do you often show older work?

OB I do, and I find it very rewarding, especially when I have not seen something for a long time. It often informs my current work and helps me to understand new ideas I have. I would love to do a show of just older works and see how they all speak to each other and interrelate.

RS Repetition seems to create what we call style. How do you define style?

OB At its best iteration, it’s being able to work with your limitations. At its worst, it’s being contrived.

Mrs. Hippy

RS Do you enjoy making your work?

OB Sometimes.

RS Do you prefer the work you made with enjoyment rather than work in struggle?

OB It depends on when you ask me. Maybe when I’m first showing it I prefer the work I made with enjoyment, because maybe I’m more confident in it. But with some distance it ends up not mattering.

RS While working, is there a feeling you find yourself returning to more often than others?

OB One of my favourite feelings when I work is when I have had a new idea and am rushing to execute it in one way or another. It feels very urgent in a fun way.

RS When you were young, did you know you’d be an artist?

OB Maybe from the age of thirteen I wanted to be an artist. But before that we moved around a lot, and things were looser for me. I moved to the US when I was fourteen and decided to study art once I was in college. Or ‘decided’ is maybe too strong a word. I started creeping towards becoming an artist. I had some really great teachers, Lee Running and Isabel Barbuzza, who blew my mind with what sculpture could be and were generally very encouraging.

RS What were you making at thirteen?

OB Drawings of dolphins and celebrities. I used makeup like eyeshadow and lipstick for drawing, to be experimental. I also made collages with iridescent stickers in order to put them on a copy machine and see how the iridescence would be reproduced by the machine. It was exciting to see the different images I would get from the same image sources.

Formula 15, 2022, foam, latex, 25 × 24cm. Photo: Kunst-dokumentation.com. Courtesy the artist and Croy Nielsen, Vienna

RS Where were you before the US?

OB I was born in Lviv, Ukraine, and we moved to Karlsruhe, Germany, in 1991. We stayed there for a year and moved back to Lviv, lived there for two years and then moved to Leipzig in Germany. After that we spent some time again in Lviv before moving to Ames, Iowa, in the US.

RS How did all these places affect you differently?

OB I had the idea to reinvent myself each time I moved, but I always stayed the same, except for the usual changes one encounters when growing up. It wasn’t always easy to adjust to constant change. Some places were more hostile than others. When I lived in Leipzig I was the most unhappy, but I also developed my interest in being creative then. I had a lot of time to myself and I would try to learn how to play guitar and record myself singing. I also spent a lot of time at music stores, listening to CDs at listening stations. There was a store called Mrs. Hippy that my friends’ older friends shopped at. It smelled very strongly of patchouli and a lot of goths shopped there. I wasn’t really allowed to buy stuff there, but I loved to go and look. There were a lot of different subcultures around like goths, punks, ravers, also neo-Nazis. Some of my schoolmates were already going to the Love Parade in Berlin at the age of thirteen. When I moved to Iowa at fourteen the scene was very different. The kids were much more wholesome in general, less angsty and edgy, more into sports and watching movies.

My most formative years were spent in Ukraine. It’s where I first thought, spoke, heard and saw, learned how to exist and relate to people, I’m not sure how to encompass that experience, because it’s the most distant and also most present. The tragedy of the war has made this distance/presence most palpable. I am safe from physical violence, but to know what a place looks, feels, smells, sounds like and now it is being blown up sent me into a different corner of reality, one I was unable to imagine before. And even with that understanding I can’t begin to approximate the reality and distress my family and the Ukrainian people are experiencing in face of the brutality and violence of the war.

RS Do you consider your history and identity to be a significant part of your work?

OB I think it shapes the why and the how, but maybe not what I make. By that I mean my history and identity are not the subject matter of my work. My work concerns itself more with formal explorations, materials that I encounter in my present, art-historical concerns, feelings etc. But I think how things end up coming out or what I am interested in has to with my history and identity. I would not believe myself if I said my work has nothing to do with my history. There is no escaping yourself. It comes through.