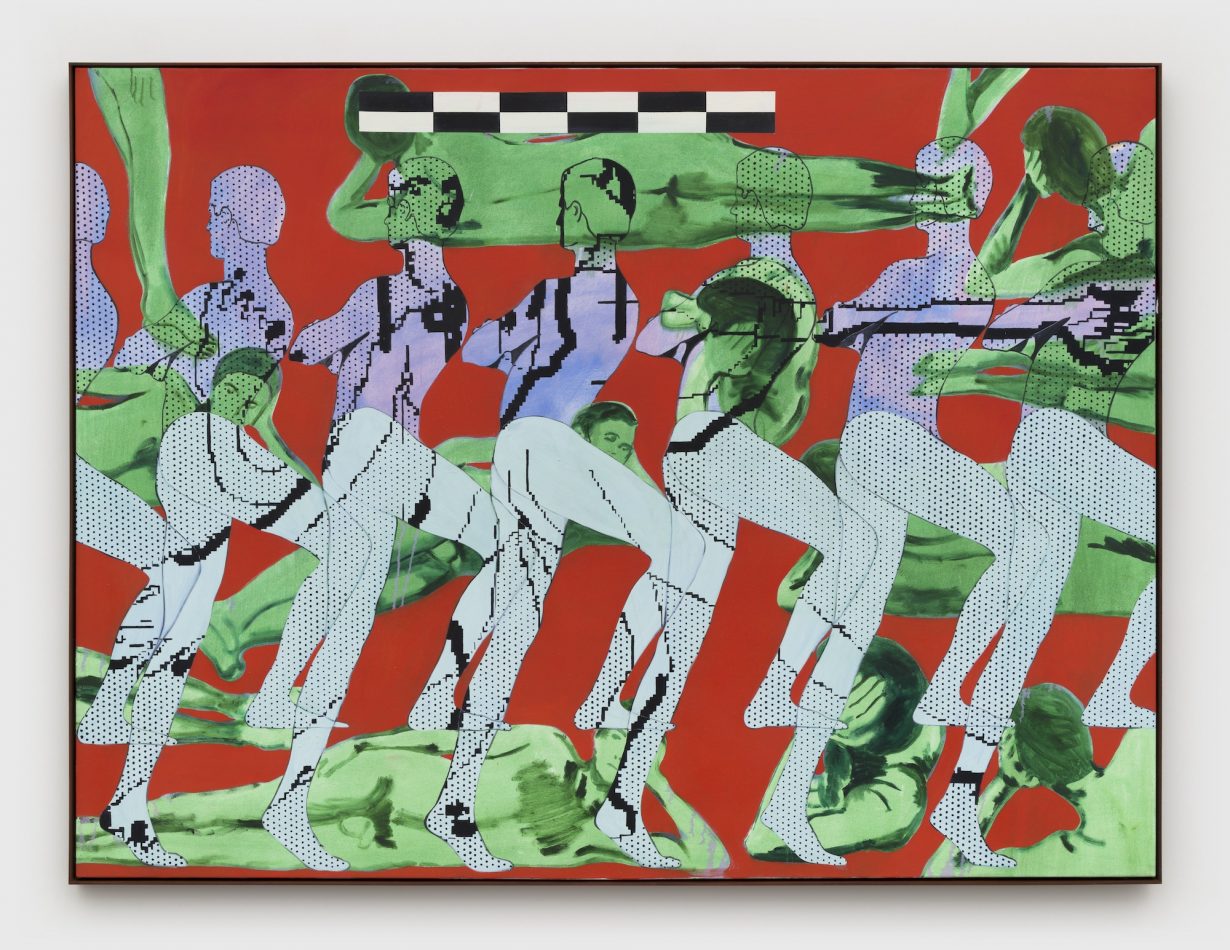

The artist’s paintings pit rough brushstrokes against graphic precision

Bastard Rhyme, Olivia van Kuiken’s first show with Matthew Brown, delivers an impressive range of oil paintings that mash up figure studies, art historical citations and freewheeling brushwork. In doing so, the works surface a debate that has become acute in the era of jpegs and Instagram: whether the force of a painting lies in the potency of its dominant imagery, as is the case in this exhibition, or in the integrity of its constituent marks. This is of course an artificial dichotomy, but one that helps illuminate the characteristics of van Kuiken’s work.

The exhibition begins with Multiply (all works but one, 2025), a large horizontal canvas that weaves together imagery from several different sources to create a sense of rhythm that evokes the Italian futurists. Van Kuiken renders generic reclining figures – think textbook illustrations – in casual strokes of transparent green. Curving chunks of blaring and opaque red carve out the negative space to form another row of overlapping bodies that appear to march across the picture with their torsos facing the opposite direction as their legs. Within these silhouetted figures we find a layer of black halftone dots and crudely pixelated lines whose edges resemble tiny irregular staircases. Though these handmade pixels lack the crisp edges of actual mechanical reproduction, they point to the idea nonetheless. By wrangling these divergent elements into a complex composition of interwoven layers, the artist demonstrates undeniable graphic sophistication – a trait that energises her work throughout the show.

However, compared to her confident manipulation of reference images, van Kuiken’s handling of oil paint as a physical material feels less resolved. The main room of the gallery contains eight vertical paintings with either figures or faces – each roughly two metres tall and three metres wide – standing upright on circular wood bases. Viewers are invited to meander through the congregation. This installation elevates the collective impact of these works considerably. Near the centre of the room stands Untitled, in which a radiant, childlike body appears in profile amid a glowing field of violet-blue speckled with irregular black dots. As you approach, another figure emerges from within the scarlet silhouette: a green chest and face looking the other way. This stark image – a cryptic double portrait – radiates a strange pathos, but its seemingly hurried execution undermines its impact. While the quick strokes of purple that surround the figures add to its strange ambience, the marks that form important features like the eyelid and nostril of the green figure lack conviction and presence.

Bad Baroque is the largest work in the show and demonstrates this paradoxical quality of van Kuiken’s work. It contains a sizeable face rendered in the tidy crosshatching common in etchings, with the word ‘Baroque’ neatly painted below. Large pools of thinned green paint seep out around two sides of this head creating gorgeous patterns that resemble a river delta viewed from above. When seen from afar, this combination of visual elements is mysterious and captivating. However, when seen up close, the dry surface of its thinned-out paint feels slightly anaemic and the relationship between its layers starts to falter. The result is a sensory experience that does not live up to the ambition of the work’s symbolism. Nearby, the postcard-size Janus (2024) takes an alternative approach to great effect: a collaged cutout of an etching furnishes the tiny panel with a two-faced protagonist. Behind the figure, a swirl of scrape marks on generous layers of oil creates a beautiful and textured vignette. Here, for a moment, van Kuiken generates powerful tension between the physicality of her marks and the graphic clarity of her borrowed imagery, creating a work with visceral and optical dynamism.

Bastard Rhyme at Matthew Brown Gallery, New York, 5 September – 18 October

Peter Brock is an artist and critic based in Brooklyn

Read next Tomas Leth’s unavailable language