Liang Shaoji at Power Station of Art, George Condo and Chiharu Shiota at the Long Museum, Karrabing Film Collective at NYU Shanghai’s ICA, Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg at Prada Rong Zhai and Jia Aili at TANK Shanghai

For those of you looking to resocialise yourselves at the deep end of art, this month sees the return of China’s two art-fair titans, Westbund Art & Design (West Bund Art Center, 11–14 November) and ART021 (Shanghai Exhibition Center, 11–14 November), both of which take place in Shanghai. Both feature a lineup of local and international galleries, although China’s strict pandemic-related quarantine restrictions will clearly limit the extent of the participation of the latter. For those of you not ready to be out and about, look out for the Chinese variant of Hans Ulrich Obrist’s ongoing Do It project (this one produced in collaboration with Cao Dan), which originally began way back in 1993 following a conversation between the globetrotting curator and the artists Christian Boltanski and Bertrand Lavier. Conceived as an alternative exhibition model, the project comprises instructions by artists for artworks that audiences can make at home. Naturally it’s a format that came into its own during the recent lockdowns. This edition features 100 instructional works by Chinese artists and artists from the Greater China region (from Cai Guo-Qiang to Chou Yu-Cheng). The book is scheduled for release late November. But be warned, even if you are avoiding the social swirl of the fair, you might want to make sure that you’re on your own before you attempt Chen Zhou’s project: Fart.

Over at the Power Station of Art, A Silky Entanglement, the sixth instalment of the PSA’s ‘Collection Focus’ series, zooms in on the work of Liang Shaoji (through 20 February). The seventy-eight-year-old’s career has been dominated by what might best be described as a ‘collaborative’ practice with silkworms that results in everything from sculpture and installation to sound art and performance. Liang’s work fuses an interest in Chinese tradition (mulberry worms were first domesticated and used to spin silk in ancient China), the intertwining of natural and industrial processes, relationships between humans and the environment and an education in tapestry at the China Art Academy. Works on show feature chairs, chains and mobile telephones encased in silk and pupae that naturally evoke our cocooned experiences of the last two years while also encouraging us to reflect on our place in the world, its cycles of life and what we actually produce during that time. For a collection show, it’s more timely than most.

A radically different view of life is on show at the Long Museum (now reopened after a two-day closure that, according to the institution, was mandated in order to balance power consumption over September’s Mid-Autumn Festival holiday), which is hosting a retrospective of paintings by George Condo (through 28 November). The American takes inspiration for his paintings from the traditions of Western art-history spiced up by samplings from its popular culture – comics, cartoons and music. The result is by turns cute and grotesque, but offers a notion of time and history that has more of the flavour of a buffet than a fixed course meal. Something that will resonate with those of us who are witnessing the rewriting of histories across the continent.

The New Museum’s Massimiliano Gioni was tapped to curate the Condo show, but the Long Museum turns its head back east for its next production, an exhibition of work (‘the largest and most comprehensive exhibition ever’) by Berlin-based Japanese artist Chiharu Shiota (through 6 March), which travels from the Mori Museum in Tokyo and is curated by its director, Mami Kataoka. While the early works by the artist covered performance, she is best known for largescale installations in which she constructs webs of thread or hoses around everyday objects. The end result will be an interesting coda to Liang’s exhibition, although Shiota’s output focuses on the network of human-to-human and personal relations, and the connections between psyche to space. A related aesthetic, then, but a different philosophy.

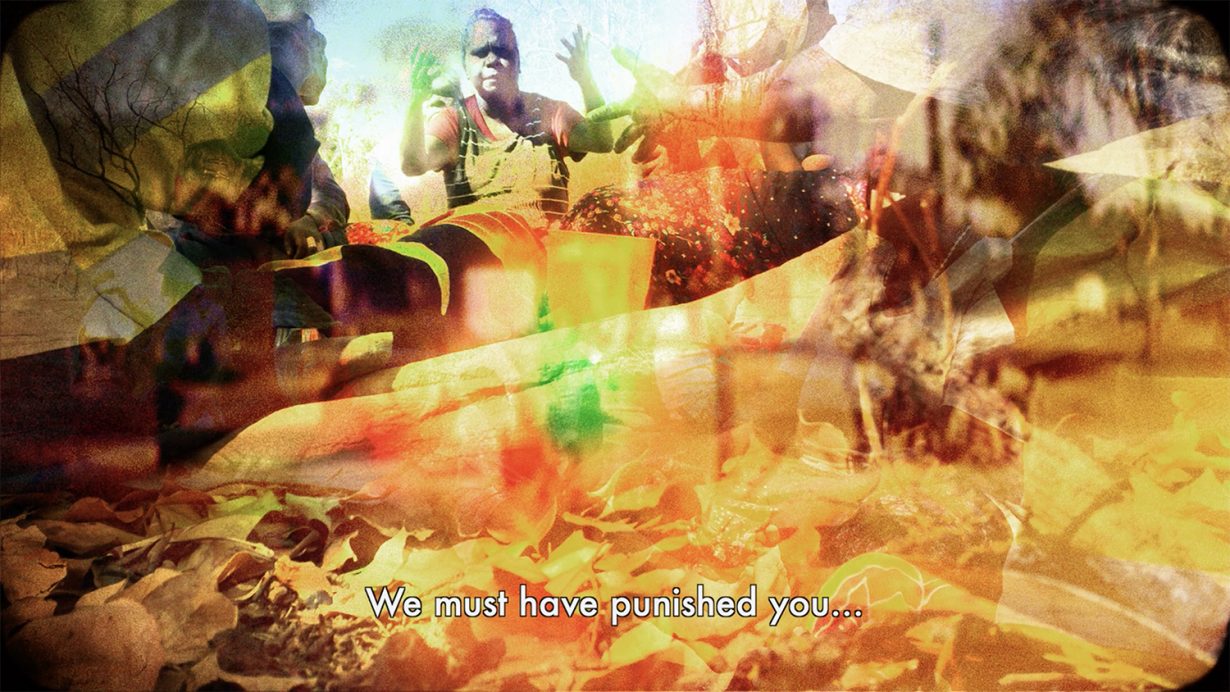

Closer to Liang’s, perhaps, is the work of the Karrabing Film Collective (through 18 December), a retrospective of which (shown for the first time in Asia) is up at the ICA at NYU Shanghai. Karrabing is a grassroots indigenous media group from Australia’s Northern Territory, all but one of whose members were born in the rural Belyuen community that developed out of what was, during the 1940s, an internment camp. Broadly speaking their work (which takes the form of films and moving-image installations) analyses contemporary settler colonialism. Or, more directly, what it is like to experience life in the communities from which Karrabing’s members are drawn and how those communities adapt their traditions to life today. In the Emmiyengal language, ‘karrabing’ describes the time at which the tide is furthest from the shore. Covered in the work are issues of land extraction and sovereignty, and notions that the land and the people who live on it are governed by systems and interconnections that are more complex than anything that can be described by a two-dimensional map. Even of the Google variety.

Those of you who are into that type of thing will want to check out Tang Chao’s Shimmer (online now), the second instalment of Shanghai’s Vanguard Gallery’s ‘nonphysical’ exhibition programme, in this case accessed via the Dianping app (best known as a way of exploring Shanghai’s restaurants and food delivery services) or Baidu maps. Keywords provided by the artist allow viewers to virtually visit geographic locations around Shanghai and encounter a series of paintings and videos that span a mixture of natural scenes to human-made environments that accumulate into a parallel and illusory second universe.

An illusory universe of another kind is on show (IRL) at Shanghai’s Prada Rong Zhai. There Swedish artists Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg (through 9 January) present a series of works that feature the former’s clay animations and the latter’s musical scores that combine in the form of installations and animations exploring the drivers of human relationships in their basest form: jealousy, lust, revenge and greed. As in the work of Condo, the cute meets the grotesque in a parallel universe in which humanity is stripped bare.

If Djurberg and Berg work to strip back our illusions about who we are, then Beijing- based painter Jia Aili takes illusion as his subject matter. ‘When we’re looking at a figurative painting, our usual response is

to focus on the perception created illusionistically rather than on the illusion itself,’ the artist said recently. ‘It’s the same in our daily behaviour: people often use the perceptions created by illusion to understand and ponder the world and measure what they see. When we look at paintings, we need to broaden our perspective and see the illusion itself, or go farther and try to experience the whole process of illusion. That’s when we may really begin to understand painting.’ While past works have featured apocalyptic landscapes with toppled statues of Lenin, Dolly the cloned sheep, naked figures sporting gas masks and burning oilfields as the ruined technological achievements of various heroic ages, Jia works with the illusory effects of geometry as well – a human figure and a circle creating the idea of corpulence, for example. The aim he suggests is to make us question easy perceptions of reality and lead us towards a deeper notion of truth. This month he leads his followers to a solo exhibition at TANK Shanghai (through 29 May).