The British artist Phillip King, who revolutionised British sculpture from the 1960s onwards, has died. King was a student of Anthony Caro, though they proved to be contemporaries and close associates. Both worked as assistants to Henry Moore, and both showed at the Primary Structures exhibition in 1966 at the Jewish Museum in New York. The American show followed a turn for King at the 1964 era-defining New Generation exhibition held at the Whitechapel Gallery in London. On seeing King and his British peers, the American critic Clement Greenberg declared that London provided ‘the strongest new sculpture done anywhere in the world at this moment’.

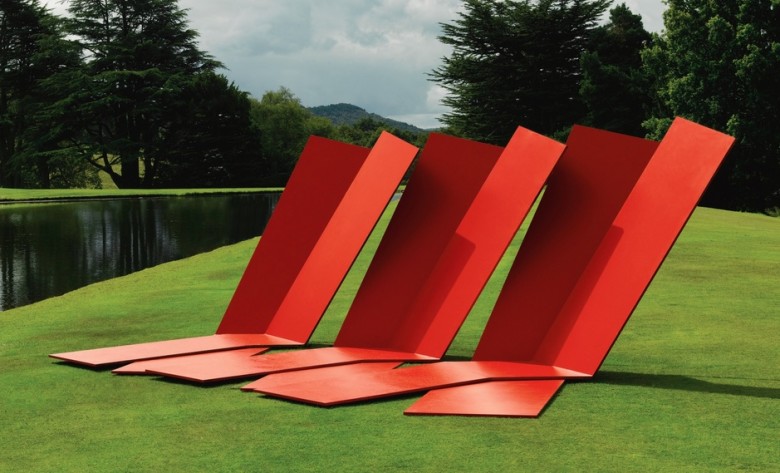

Previously King’s sculptures were influenced by such earlier artists as Michelangelo, Rodin and Picasso but in 1960, he scrapped all his previous work after being exposed to American Abstract Expressionist painting. From then on his practice was characterised by a profound interest in industrial materials and abstract form. Genghis Khan (1963) consists of a black fibreglass conical form from which wing-like armatures are proffered. Call (1967) is a group of large-scale objects, and the first work that King made in steel: two blocks and two columns painted in orange and green. While he continued to experiment in other materials, including a notable foray into ceramics after a trip to Japan in the 1990s, steel would become his signature material from thereon. Green Streamer (1970) features a series of interconnecting green-painted stainless steel plates.

In 1990, he was made professor emeritus of the Royal College of Art in London and was the president of the Royal Academy of Art from 1999 to 2004. In 2010, the artist received the International Sculpture Center’s Lifetime Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture Award.

Ahead of a 2014 retrospective of his work at Tate Britain, he said of his career, ‘Sculpture might ostensibly be the most visible of arts in that the viewer can quickly gauge size, weight, colour and so on, but there is also something that escapes you in the most mysterious manner. It can never be totally visible in the way that a painting can, where surface is everything. With sculpture, there is surface, but there is so much more going on behind… Exploring that sense of mystery is one of the things that has kept me making things for all these years’.