Mark Rappolt speaks with the director of FRONT 2022 about art as a form of healing, the nature of representation and the (after)life of a show

Postponed by a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the second edition of FRONT, the Cleveland Triennial of Contemporary Art, opens to the public this summer. Put together by a curatorial team led by artistic director Prem Krishnamurthy, FRONT 2022 is titled Oh, Gods of Dust and Rainbows, which itself riffs off the opening line of a 1957 poem by the American writer and social activist Langston Hughes, who had spent part of his childhood in Cleveland. Internationally known for his work with the design studio he founded, Project Projects (which in 2018 became Wkshps), Krishnamurthy is also known for his work with the exhibition space P! which he founded in New York. Based in Berlin and New York, he additionally works as an artist and author (among other things of the ever-changing electronic book P!DF) across a variety of media, and as an independent curator. Among a number of other workshops and community-based fora, he organises Commune, an ‘emergent workshop that practices artistic tools for social transformation’. FRONT 2022 will feature over 70 international artists across 20 museums and other venues in Cleveland, Akron and Oberlin. ArtReview caught up with Krishnamurthy to explore some of the thematics of the exhibition, among them care, collaborative working practices and connecting artists to local communities, and to discuss the role of curators and artists in the post-pandemic world.

ArtReview What does FRONT mean to you?

Prem Krishnamurthy That has changed over the course of my multiple engagements with it. The relationship began when my design studio [Wkshps] developed the graphic design for the first edition of FRONT in 2018, which was a very different mode of engaging with it. I had never visited Cleveland before that project began, but through it I got to know the city a bit. By then I had already been working in Pittsburgh on the Carnegie International for a number of years; so for me it was an encounter with another Rust Belt city and I was able to use this comparison and contrast to try to make sense of that.

When we [Tina Kukieski and I] started work on the second (and current) edition, it was still before the pandemic – we started really thinking about it in late 2018. We looked at the landscape of Cleveland, Akron and Oberlin, and out of that, quite organically, came to the idea of thinking about art as a form of transformation and healing.

AR It’s interesting that you came to that already before the pandemic, during and after which issues of care in relation to art have come more prominently to the fore. How did that mode of thinking come about?

PK It emerged from the context of observing that this was an area of the country that once enjoyed a great degree of prosperity and wealth, produced by industrialisation and the availability of labour, but which in turn led to a lot of environmental destruction, alienation and widespread social problems. Though all of that industry has largely left the region, what you now see is a concentration of healthcare and biotech as the main employers. But equally you also can find an embedded history of care in Northeast Ohio. Alcoholics Anonymous having started in Akron [in 1935], and in Cleveland you have Art Therapy Studio [founded in 1967], which is one of the first independent art therapy organisations in the country. That’s to name just two, among a wide range of community-based and religious organisations. So we were thinking about an odd mixture of real exploitation and a really challenging history, but with a lot of institutions, infrastructure and smaller-scale, bottom-up models for community building.

AR How do you think art can act as part of a process or form of healing? There’s a long history of culture being deployed as a signifier of actions that aren’t actually being performed by the people who should be performing them – whether it’s government on various scales or society more generally. As a screen, in a way, that makes us all feel better, without any real problems being addressed.

PK That was a question I asked myself in the first months of the pandemic, amidst the first lockdown. I thought, what is the point of art? We have these much larger problems. We have systemic racism, we have white supremacy, we have a failure of social systems. We have a lack of infrastructure, particularly in the US, that cares for people. What can art actually do?

It was a real crisis both personally and curatorially for me. But where it led is to an exhibition that will try to test out some well-developed hunches and to see what sticks. We’re working from the idea that art can transform and heal on multiple scales, but in different registers. Sometimes people have an unrealistic expectation that art can make everything OK. It can be a community agent and also be beautiful, and all of these other things at once.

We are approaching this issue by framing art as a transformative healing force on three scales. First, at the scale of the individual and how the making of art on an ongoing basis, as a daily practice, can be something that’s healing, liberatory and transformative.

Second, on the collective scale. Here I’ve really been informed by Audre Lorde and others, in thinking about the role of pleasure, the role that sharing joy between people – and other beings – can play. The basic premise is that aesthetic pleasure actually offers a strategy to bring people together across difference.

At its most fundamental form, we are considering music and dancing and how those forms are so rooted in every human culture. They form the basis for creating community. The opposite to this is people wearing headphones on the subway nowadays; contemporary society is very atomised, especially now, even behind our Zoom screens. So, for me, there’s a glimmer of hope there – directly in joy, in movement. From the beginning the show included a lot of dance-based works; projects that are public and include music and use music. I mean, not to ‘use’ music because that sounds too instrumentalising.

AR Doesn’t every curator ‘use’ the things they include in an exhibition?

PK Yes and no. Hopefully it’s a mutual effect: you both include them for a particular reason, but then they also do something you never expected.

The third scale is where I’m looking to the future, but where I also have more questions. In many ways the show for me personally is just one step; it’s already becoming clearer to me that afterwards I’ll need to ask new questions. At this third scale we’re asking how art can speak with power. How can art be transformative on a structural level? For the last 500 years, more or less, artists have sat at the same table with the people who hold power – economic, social, political and spiritual power – particularly within a European context. This proximity gives them direct access to those vectors of power. In tandem artists are able to work in a speculative way, to rethink systems, or to test out new ways of being. A part of me is a utopian optimist who believes that because of those two factors artists have the opportunity to at least nudge some of our larger systems in one direction or another. There are artists in FRONT 2022, such as Cooking Sections or Cassie Thornton and others, who are working in this more systemic way. We are also emphasising collaborations between artists with communities and institutions that otherwise wouldn’t happen. I think every exhibition, every artwork, everything, has to create its own kind of publics, its own intersecting group of people who come together around it.

AR Is that your job as artistic director?

PK Well, yes and no. I wouldn’t say it’s my job. This is the funny thing: I’m the artistic director, but I’m the artistic director of a triennial that includes over 25 venues run by more than 15 different institutions, all with many different curators working at them. I think my job is to offer some tools or strategies for how each institution can work towards that. It’s much more of an exercise in modelling, almost a pedagogical role, but one where I’m learning at the same time as I’m trying to be as transparent as I can about the process.

Here’s a prime example: one of the projects that has already opened, but continues to unfold in other formats, is a collaboration between Jacolby Satterwhite, the Cleveland Clinic and the neighbourhood of Fairfax, a historically black neighbourhood in Cleveland on the east side of the city. Jacolby had never worked on a public art project before; the clinic had never worked on a public project with an artist with this kind of approach. Neither one of them had ever tried to do something with the neighbourhood directly. My role ended up being almost like a facilitator. I organised Zoom community meetings. At times when there were frictions in the conversation between the commissioner and the artist, I stepped in to help mediate that conflict and then share how I approached this role so that hopefully next time they could do it themselves. I think it’s almost more about multiple methods and prototyping than it is about a singular solution.

AR Do you think that’s how you see the role of the curator in general or just in this specific instance?

PK I’d like to see that as the role of the curator in general, but my approach – like anyone else’s – emerges out of my biography and past experience. I come to curating from the field of design, where ultimately I’m just as interested in the exhibition and how people experience that as I am in the processes that we employ to develop the project. An exhibition is just one step in a string of prototypes; then it continues in all of these other ways. Sometimes when people think of curators, they think that the curator’s job is just to talk to the artist and figure out how their work is commissioned, developed and presented. Whereas I believe the curator has to stand with the artist, but also try to negotiate with other communities and with larger concerns – planetary concerns, social concerns – and try to triangulate between them all.

AR It seems a lot of what you’ve been talking about concerns the nature of representation in a way, and the idea that there’s a point at which it’s not necessarily helpful to focus on representation, but to try and move that into a kind of reality. Is that something you feel you’re trying to do with this exhibition?

PK I’ve always been much more interested in performance than in representation. I’m interested in how things land, how they’re embodied and how people experience them and enact them. I’m much less interested in showing a problem.

AR Do you think that leaves you and the artist with more of a responsibility than it would do were it just in galleries or just about representation?

PK Probably. Once you get out into the world, for example, with any of the projects we’re doing in public spaces, they have so much more at stake. When we invited Julie Mehretu to make a massive public mural in downtown Cleveland (which will not be open for the triennial this year, but is starting during the exhibition and will open next year), she came to visit Cleveland. In one of the first meetings, she said, “This is a big responsibility. If I’m going to make a permanent mural, which will be on a 100-foot wall for a long time, I need to make sure that this thing is not just an alien that drops in. It needs to interface with people.” We actually had about a year and a half of dialogue, of talking through the project with her, her studio, connecting her with different people, connecting with different histories of Cleveland, and making sure that it actually does make sense.

AR So with the example of Julie Mehretu you have works opening after the run of the triennial. Did you think a lot about the life of the project and the afterlife of the show?

PK Yes, that’s always been part of the thinking. It just seems harder and harder to justify – on any number of levels – putting the entire expenditure and investment of time, energy, money, labour into making a thing that exists for three months. Over the last several years, especially after running P!, my exhibition space in New York, I’ve been preoccupied with how exhibitions always have a prelife and an afterlife. They come out of something and then they have something that emerges afterwards. It’s much harder for institutions to think that way, because they operate in a different temporal framework, but this particular philosophy was built into our curatorial framework from the start. There are projects like Julie’s, for example, as well as by Kameelah Janan Rasheed, who has been working since 2019 on a long project with the Cleveland Public Library. She’s been developing works with branch libraries and young artists. Part of these works will be in the triennial and part of that will extend beyond the triennial’s official close. Julie is curating an exhibition at the Cleveland Museum of Art, which is the first time they’ve mounted an artist-curated show. It presents some of her work and reveals some of her thinking and references across a range of work from nearly every department. This becomes the starting point to launch the public process of the mural, which will be done next year. Then there are other artists like Cooking Sections, whose project involves a three-year fellowship with regional farmers that will take place after FRONT 22.

This focus is also a very personal response for me. It comes out of my own experience, making fast-paced exhibitions in New York that are meant to be consumed by art people, critics, collectors, in a very easily digestible way. It has made me realise that for myself, at least, I need to try to practise a slower form of curating or slower exhibition-making that builds into its process an idea of what might happen in the future, without being prescriptive.

AR Did you ever think with the theme that you have that ditching the cultural institutions entirely and using the social, medical and other designated caregiving structures would be more interesting?

PK It definitely crossed my mind. But the way the triennial is structured is an important factor. Its partnership model is in collaboration with a core group of cultural institutions, which did not significantly change from the first edition; though, then, part of the remit of each edition is to try and expand that challenge, redefine the sites and contexts of the show. Cassie Thornton, for example, is creating an installation at the National Museum of Psychology in Akron. Part of her project includes a set of workshops and programmes that go outside of the art context. They are focused on a distributed peer-to peer health model, The Hologram, that thousands of people in the world are already practising, but she’s using Akron as an opportunity to continue to prototype it and share it with new communities there.

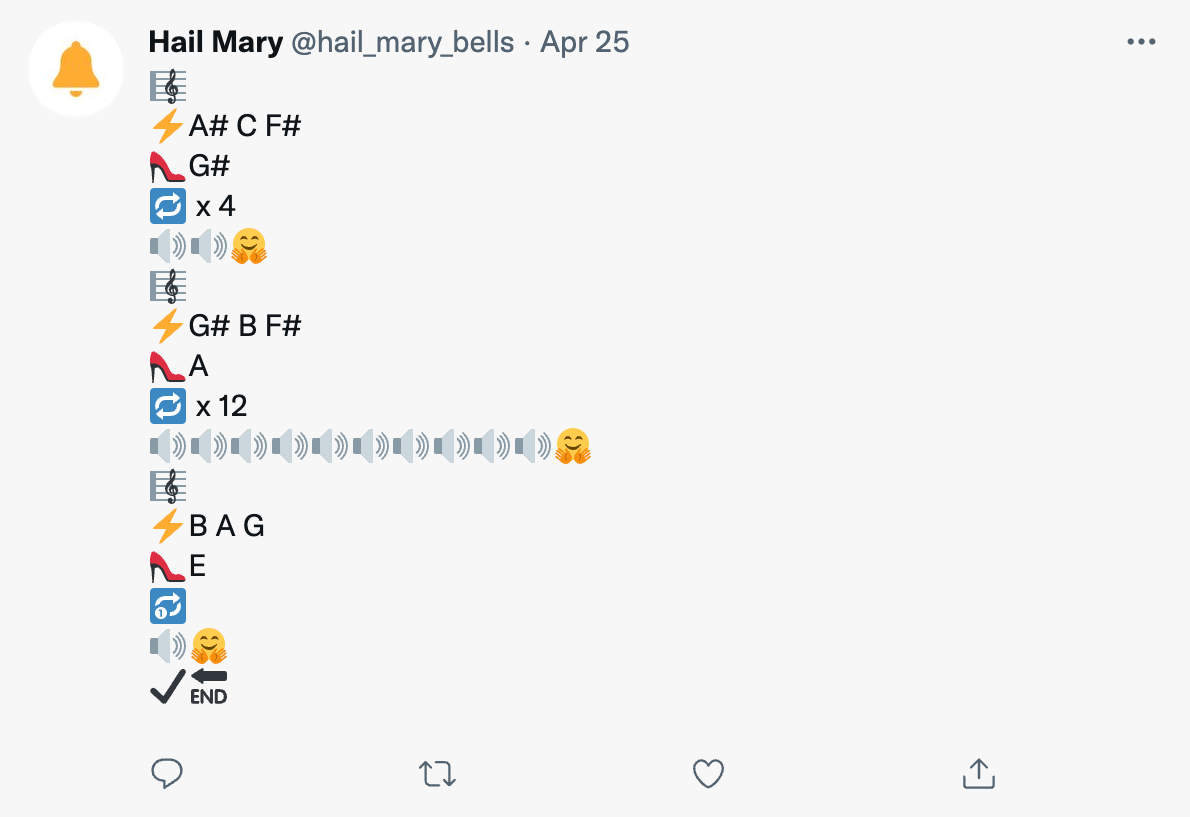

Another project that excites me, because it can do something very compactly, is by Cory Arcangel, who was born in Buffalo and went to school at Oberlin College in the conservatory. He is creating an algorithmically generated visual score-based composition for carillon bells, and then the carillon players at the McGaffin Carillon at the Church of the Covenant in Cleveland will simply interpret and play it immediately. There is a whole network of other carillon players throughout the world who will also perform at the same time. This is a very lightweight project, an ephemeral gesture. The main people who will hear this particular work in Cleveland are in-patients at University Hospitals. It’s a very different audience.

AR How much did your thinking about the show change during lockdown and in relation to the pandemic?

PK The largest change was to reconsider how it would take root locally. Which may sound odd because I couldn’t travel to Cleveland for a year and a half during the pandemic and most of the team was working remotely. But that was the period in which Annie Wischmeyer, FRONT’s curator on the ground, conducted over a hundred studio visits remotely with various artists based in Cleveland and in the region. This led to a series of new commissions and invited artists. In the first phase we were focused on artists working nationally or internationally who related to Cleveland in a particular way. Yet we knew that our intention was to strengthen the local artistic community. That imperative became even more important during the pandemic.

Another thing is we emphasised collaborative projects of different kinds even more. Jacolby’s project, which I mentioned, started during the pandemic. It built on the idea that, even if we couldn’t travel to Cleveland directly, we could connect Jacolby remotely with artists in the city so that they could work together on a community-based project. It also resulted in projects like that by Sarah Oppenheimer and Tony Cokes. They had never met before we introduced them through Zoom, and then they developed a project in conversation with each other. So the pandemic didn’t radically change the focus of the show since we had already developed its theme and focus, but I think that it tweaked and sharpened our methods. Plus, it gave us an extra year, which meant we could pursue certain longer-lead projects. Some of these longer-term ideas probably wouldn’t have taken place if we’d opened a year ago.

AR Given the longer-term nature of the process, should we expect a highly finished body of work in the exhibition?

PK C’mon, you know the deal! Somehow things always are done when they need to be done. Some things will be polished, others still rough around the edges. But to be honest, I hope that we don’t see only totally smoothed-out, buttoned-down presentations. As Murtaza Vali, who is part of our curatorial team and curating the presentation at the Akron Museum of Art, said during one of the discussions with the museum, “A triennial ought to be propositional”. A show like this, with so many different parts and partners, will inevitably be a little bumpy. But the beauty is that it opens up questions, and hopefully engages you in the process. That’s what the format is meant to do, not to just show up and say: here is a slick, easy-to-digest product. Every exhibition is the rehearsal for the next exhibition.

FRONT International 2022, The Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art, is on show at various venues, through 2 October