In the context of MACBA’s ongoing affair with art-as-archive, and the thematic rehang of its collection, Seep has been set up to read as ‘journalistic art’, a claim supported by the topicality of its subject, Iranian modernity. But as the imprisoned Iranian-born Newsweek journalist Maziar Bahari found to his cost, this is not a country tolerant of even objective critique from within. That artists Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi – also known for the Farsi/ English publication Pages – still work out of Tehran understandably precludes their taking any radical stance: but what kind of journalism pulls its punches?

Seep explores two distinct archives. The first, belonging to British Petroleum, includes documentation of a promotional film aborted prior to the nationalisation of Iran’s oil in 1951; the second is the £2.5 billion cache of artworks acquired in the mid-1970s but banished to the basement of Tehran’s purpose-built Museum of Contemporary Art following the Islamic Revolution of 1979. In finally realising the former and exposing the absence of the latter, Tabatabai and Afrassiabi stage a recontextualisation that promises insights into Iran’s troubled path to modernity.

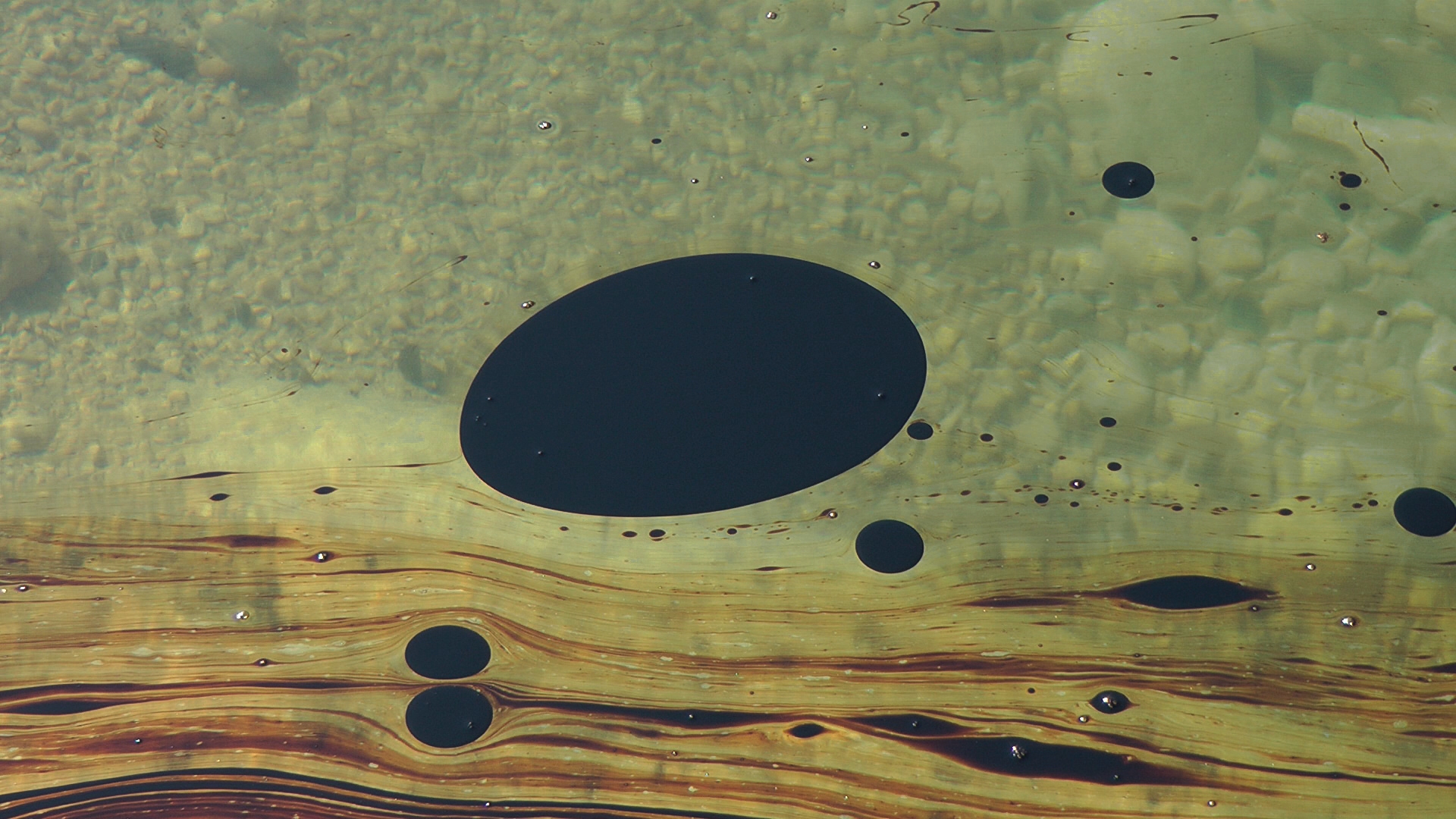

Of Seep’s two central videos, one is a road movie in search of the eponymous black stuff and loosely follows in BP’s footsteps, the other a more poetic musing set to a reading of the original filmmaker’s conclusion that, devoid of visuality, the quest for these seeps was ‘unfilmable’.

Western oil exploitation is a soft and politically loaded target. The obvious reading here is the industry’s disregard for the environment, one the show’s curator, Soledad Gutiérrez, eagerly encourages. Yet far from being another Deepwater Horizon, oil seepage is, I discover, a natural phenomenon, known and exploited for millennia. Having worked up an unjustified lather against BP, I feel duped: this is less Newsweek than National Geographic.

Among other artefacts tenuously grafted to the installation is an incomplete list of Tehran’s absent holdings of Western art and a model of the museum’s spaces. But although the 1,500 works are said to have been ‘unseen’ for 33 years, a (necessarily limited) showing of them was arranged for the Revolution’s 20th anniversary, and it is possible to view at least a selection by appointment. Having done so in 2002, I can attest that the sequestration of this coffee-table panorama of blue-chip masters is no great tragedy: far more is lost to private collections. And on the plus side, the museum’s vacated walls provide exhibiting opportunities for younger Iranian artists otherwise denied a voice.

Effective journalism is direct and unambiguous; art, one hopes, leaves the reading open. Irrespective of its post-Greenbergian return to content (a theme of MACBA’s current rehang), art retains the potential for embracing that elusive other: the aesthetic. While Seep’s journalistic punches are mostly feints that won’t bloody any noses, the depiction of these oil seeps amid arid landscapes reveals an unremarked-upon beauty: marbled like endpapers or else dense, black and impenetrable. Yet the unwillingness to engage with the visual and visceral implies that ‘beauty’ itself is the dirty word here.

This reluctance to acknowledge the aesthetic mirrors, a tad ironically, the Islamic Republic’s own censoring of ‘decadent’ Western art. It will be interesting to see if Seep reads differently in the context of London’s Chisenhale Gallery this spring.