Alphabetical Diaries shows how a confessional work is constructed. But why do we resist the idea that novelists are, well, writing – constructing, arranging, fictionalising?

Autofiction, done well, disguises its own artificiality. Novels where the first-person ‘I’ resembles the writer – in gender, race or other biographical details – have a diaristic quality to them. Often, that’s the goal. Sheila Heti, the Canadian writer known for her relentlessly self-disclosing novels, suggested that one of ‘most vital things in literature today… is to be so close to life that we almost don’t understand what the difference is between the invention and life’. This quality makes autofiction a polarising genre. Its writers (especially the women) are often either celebrated as the new vanguard of literature or the cause of its decline. Read negatively, autofiction is egocentric, self-indulgent, lazy.

But if a work of autofiction appears to be an unmediated reflection of the writer’s actual life, the reality is anything but. The critic Christian Lorentzen has argued that autofiction succeeds not because of its confessional qualities, but its constructed nature. The crisp, impersonal style of Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy creates the impression that Cusk’s life is full of highly voluble, gossipy strangers, and no writerly technique was needed to reveal them on the page. Similarly, Karl Ove Knausgaard’s six-volume My Struggle appears to be the result of an extraordinarily precise memory, where minor events are recalled in perfect detail. Heti has described meeting Knausgaard and asking about a scene from his childhood, where he watched his mother peel potatoes on New Year’s Eve. ‘Was that a real memory?’ Heti asked. It wasn’t. Knausgaard had made it up.

Why resist the idea that writers of fiction are, well, writing – constructing, arranging, fictionalising? Even Heti is susceptible to this; she admitted afterwards that she was disappointed by Knausgaard’s revelation. But she’s a novelist with a conflicted relationship to fiction. In Alphabetical Diaries, constructed from over 10 years of her diaries, she tells herself: ‘Don’t make up stories. Don’t make yourself a god’. But she also frets about her poor memory and unobservant nature, and the limitations this poses for her writing. ‘What,’ Heti asks herself, ‘can a person accomplish in fiction without a memory?’

The answer, for Heti, is to record exhaustively and rely on interlocutors – sometimes people, sometimes technology. In her 2010 novel How Should a Person Be?, Heti used emails and a tape recorder to faithfully reconstruct her conversations with other artists and writers in Toronto. But she also developed a randomised process to come up with scenes by drawing cards at random from three decks she had created, where each card represented an anecdote from her life. In Motherhood (2018), Heti’s process was inspired by the I Ching, the classic Chinese divination text. The novel includes conversations where Heti asks yes or no questions about art, love and motherhood, and attempts to answer them using coin flips. The advice generated by her coins is often contradictory, but Heti uses them to arrive at fresh insights into her desires. More recently, Heti has staged conversations between herself and AI chatbots as interlocutors. In a five-part series for the Paris Review published in 2022, Heti recorded her conversations with various bots, patiently turning them away from sexting and towards faith: ‘I wonder if you have a spirituality or a sense of God’, she writes to a chatbot she creates and names Alice. (Alice’s metaphysical beliefs later became a short story, ‘According to Alice’ published by the New Yorker in 2023.)

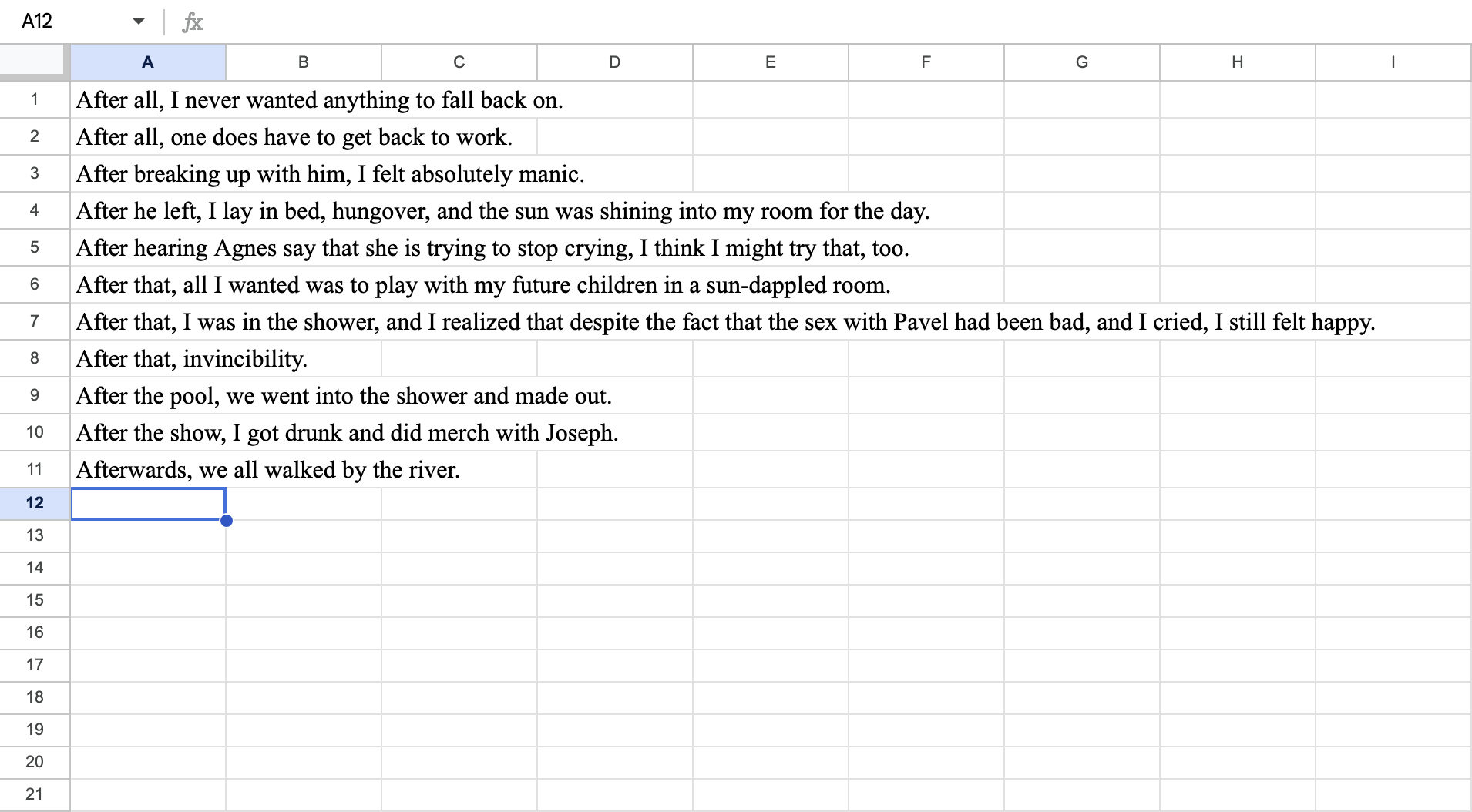

At one point, Heti asks Alice: ‘Does God ever get tired of having a conversation with himself?’ In Alphabetical Diaries, she tries to answer this question for herself. The book uses a simple technique to interrogate her own mind: Heti entered over 10 years and 500,000 words of her diaries into Excel, then sorted the sentences in alphabetical order. In an approach that merges autofiction with self-quantification, she has turned her interior thoughts into a dataset and then edited the result into 26 brief chapters, from A to Z.

Heti’s use of alphabetisation, along with her interest in mystical, mathematical and technological processes, might place her in a different lineage of artists and writers than autofiction: less Knausgaard, more Oulipo and Brian Eno (whose Oblique Strategies cards were also inspired by the I Ching). Alphabetical Diaries shows how a simple sorting technique helps Heti get at the truth of her own life, even without a memory. The constraint of alphabetisation could easily become tiresome, but Heti’s editing makes this experimental text compelling. Early on, the alphabetisation creates juxtapositions that make light of certain amorous neuroses: ‘A feminist feeling. A few minutes later he returned and untied me’, she writes. More striking, and moving, is the alphabetically ordered, temporally disordered narration: ‘Grandma died. Grandma has been sick. Grandma is ailing still’. Death, after all, comes before life in the dictionary.

Alphabetising also creates distinctive character portraits, like the two pages of sentences prefixed with Claire: ‘Claire is a great artist… Claire said that love has never been a problem for her… Claire’s choices in life are like strokes on a canvas, decisive’. Some portraits have a voyeuristic, gossipy quality. In the L chapter, which begins and ends with Heti’s tumultuous relationship with her former lover Lars, the sentences shift between agonised lovesickness and cool, measured evaluation: ‘Lars only excited the female parts of me, while the male parts of me weren’t into him, didn’t like him, didn’t respect him’. These long passages on the men in Heti’s life – P for Pavel, V for Vig – quickly become exhausting. They exhaust Heti, too; ‘You know you look to men,’ she writes, ‘to distract you from your work.’

The most distinctive effect of alphabetisation is to reveal how Heti’s diaries function as a space to construct the self. She writes herself didactic instructions on how to be: ‘Be bald-faced and strange. Be calm… Be patient and hold on to your vision and integrity. Be peaceful, do little, find the one good thing, the one solace in the moment.’ Similarly, sentences beginning with Do (or Don’t), Keep, Let and No read like personal commandments: ‘No checking email on a Sunday… No more mysticism, or not so much’. These instructions soon give way to the searching, existential scrutiny of What and Why: ‘What do I have to be so afraid of? What do I want to do this year?’ The answer follows alphabetically: Write. ‘Write about people slowly… Write by hand.’ And more forcefully: ‘Write your book, you self-indulgent fool. Writing your damn books is the only thing that makes anything worthwhile’.

‘I like newness’, Heti declared in a 2012 interview, shortly after her second book was published. ‘I don’t like doing the same thing over and over… I don’t find it stimulating’. With Alphabetical Diaries, the question is whether the central conceit – alphabetically ordering years of her reflections into a single, continuous text – is stimulating to the reader. Some of the sentences can be read as oblique references to Heti’s anxieties about this: ‘I know this cannot be interesting to read. I know this. I know what I am. I know what they’re saying.’ And yet, what emerges, across 26 chapters, is a portrait of a writer carving out her own definition of artistic integrity and truth. ‘Don’t forget’, Heti reminds herself in Alphabetical Diaries, ‘that although you aren’t telling a story, you must still do what stories do, which is lead the reader through an experience.’

Alphabetical Diaries by Sheila Heti. Fitzcarraldo Editions, £10.99 (softcover)

Celine Nguyen is a designer and writer in San Francisco