In their latest work, the Chengdu-born Minnesota-based artist embraces the unknown

Shen Xin’s latest work, a five-channel video installation titled Brine Lake (A New Body) (2020), is, in part, about attempts to construct a narrative, or multiple narratives, out of materials that are absent. Although I wonder whether the fact that we are talking about the work via Skype, between Minnesota (Shen) and London (me), as, on one level, two absent presences, is further conditioning me to think this way. I wonder if people in general are not conscious enough about how these forms of communication, with their substitute presencing, alter our perceptions of what is ‘really’ present. Or maybe that’s just me. Which perhaps is a way of saying that I worry that I don’t worry enough about how social distancing and lockdowns might be affecting the way in which we perceive reality. About whether or not they lower our standards for and expectations of ‘reality’, make us immune to really thinking about what’s present and what’s not. Not that this wasn’t already happening before the current pandemic. Like many other issues, the pandemic just seems to have brought it to the fore.

“As witnesses of new technologies, it is certain that we will never remain unchanged,” says one of the protagonists in Brine Lake. Although she is, superficially at least, talking about technology in the context of something else.

On Skype we begin by discussing pandemic living conditions. I mention the new restrictions that have been imposed in London to effect greater social distancing. Shen replies by saying that “we [in Minnesota] live in cars, so we don’t come into contact with other people”.

“My office in our company looks a lot like this room. Do you like it here?” asks another of Brine Lake’s protagonists at the beginning of what appears to be a business conversation. It comes across as an icebreaker, an attempt to forge a personal connection. (A recurring theme in the work.) It’s empathetic but strategic in the ostensible context of a business meeting. Although to the eyes of the viewer there is no context to speak of. There is no ‘actual’ room onscreen. Just a blank, empty set.

Brine Lake is due to be completed at the end of October, two weeks after our conversation. So, in a way, it too is an absent presence. I have seen extracts from each channel, singly, on a computer screen, but not the five-channel whole, which is due to go on show as part of the Gwangju Biennale, now postponed to 2021. So anything I have to say about the work as a whole is to some degree a projection, a type of fiction, an incomplete translation. Which, when it comes down to it, is how we talk about most experiences of art. But I mention it here, in the case of Brine Lake, because I’m particularly aware of it in the context of an artist, like Shen, in whose work modes of display, as much as modes of representation, play a crucial role.

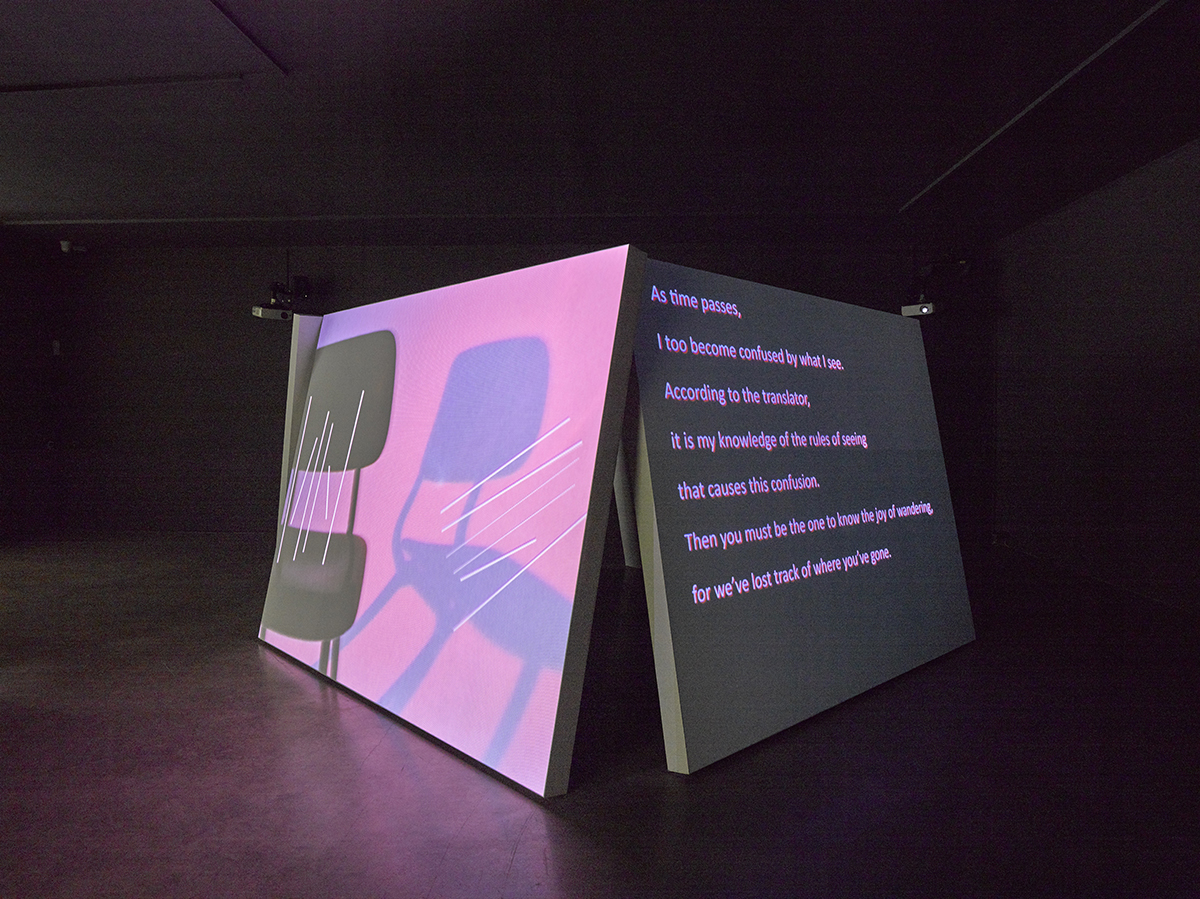

The four-channel video installation Commerce des Esprits (2018), for example, offers two channels of animated text (in English and French respectively) and a Chinese voiceover, alongside two channels of motion-capture video (in which the body being captured is reduced to a vaguely skeletal combination of points and lines). On a narrative level it combines (more and less obviously) the memory of Shen’s father, who died following a 24-day coma, the voice of the artist’s mother, the works of Zhuangzi (who, during the fourth century BCE, wrote one of the foundational texts of Daoism), research by French sinologists into the works of Zhuangzi, and meditations on the act of translation. Like most of Shen’s work, it embraces complexity and accepts lacunae. But when you see Commerce des Esprits, it appears, initially at least, as an object of physical and sculptural simplicity: an approximately cuboid structure made up of four screens or planes, arranged such that each plane appears to support the one next to it. Like a hastily constructed room with text and imagery appearing on its outside walls. A sculpture that appears to be talking to itself as much as it is talking to us. An animate, conscious form.

Brine Lake also centres on a script and acts of translation. The former is written by the artist, and translated into Korean, Japanese and Russian. It’s performed in these languages by two female actors, always against that empty black set, with English subtitles. The narrative centres around two representatives of separate fictional companies who are visiting an iodine recycling factory (we are not given details of its specific location) in order to set up some form of business relationship. One of the representatives speaks Korean and Japanese, the other Korean and Russian. At times the second speaker struggles with the latter language.

These representatives are videoed, head-on, speaking to factory employees separately and, in one channel, together, but we only hear one side of the conversation and can only read one set of subtitles: the voice and presence of the factory employees is absent, the subtitles relating to their speech blacked out. Instead, the camera moves back and forth, and side to side, focusing on the representatives alone. There’s a suggestion of intimacy as the camera zooms in on faces, and awkwardness as the camera, which we are led to presume stands in for the eyes of the absent factory staff, sways, as if those staff were constantly shuffling around.

Yet the setup works like that earlier icebreaker. We find ourselves starting to guess as to the absent content of the conversation, and slowly we begin to stand in for a missing person, filling a void that is made manifest in the form of an emptiness in time (the time in which the unheard voice, with its censored subtitles, is speaking), space (out of shot) and representation. We feel a certain responsibility. We want to give agency to the presence that has none. The voice that has been censored. While, at the same time, in strictly logical terms, we’re engaged in a process of invention. Interpreting nothing, translating nothing and empathising with nothing to boot.

The factory employees, Shen suggests, are “ghosts”. And, as one watches Brine Lake, the uncertainty that now surrounds who is talking to whom soon morphs into an uncertainty as to what the conversation is really about. Discussions about iodine processing (for most industrial manufacture, brine is acidified, oxidised, filtered and purified – transformed from liquid to solid, to vapourised states), the extraction and manipulation of something born of the conditions of the land (iodine, as one of the representatives puts it, derives from organic animal and plant debris on the ocean floor), and its eventual recycling (following its use in things like the production of fluorochemicals, or as a component of X-ray media materials, for example) start to sound like discussions about reincarnation: “death without decay”, as one of the participants puts it. Conversation continually slips from the impersonal to the personal; discussions about companies working together flicker between both individual and corporate backgrounds and intentions. Just as discussions about the origins of the foreign machinery used in the factory morph into discussions about mother- and fatherlands. At one point, iodine seems to be speaking for itself: it’s too raw, hence its reliance on technology to refine it; its malleable properties make it submissive. And quickly the discussion of technology becomes a discussion about mechanisms of power and control. The censored part of the dialogue feels more sinister still. Questions of how and in what language to communicate crop up; what’s comfortable and what’s not. “I think you can understand what it means to convert something that is associated with you by birth but is inherently foreign,” one of the characters states.

Drip by drip, it becomes clear that the subject of iodine recycling conceals another topic of conversation. A conversation about state- lessness and the history of Korea’s conflicts and colonisation over the past century. “About assimilation, recycling, revaluing, devaluing, relationships with former states and future homelands,” as Shen puts it. Perhaps about Sakhalin island, then called Karafuto, where Japanese forces invited and forced Korean labourers to move during the 1930s and 40s in order to fill labour shortages. Russia invaded the island shortly before the Japanese surrender at the end of the Second World War, eventually repatriating the Japanese but leaving the now-stateless Koreans stranded. Until the mid-1980s, when Japan offered to repatriate what was by then several generations of ethnic Koreans. Only a small number returned to Korea. “Stateless people create fear,” one of the protagonists says.

In effect Brine Lake offers a form of role reversal, giving a voice to those who generally have none. It’s the product of Shen’s ongoing research into conditions of statelessness in East Asia. But without overtly locating that within the context of conflict or, as Shen puts it, “nationalist histories”. “This embodiment of the unknown leaves you with something that’s up to you to decide what it is,” Shen says. “Your relationship with it and how you participate, whether it’s about the environmental concerns, or your relationship with the land or with people in general, or the idea of home and homeland – is something that I think about a lot during the pandemic.” Beyond the metaphors and translations, in Shen’s work that translates into a form that gives agency to actors and viewers alike.

The Gwangju Biennale takes place from 26 February to 9 May