This past March, when Hillary Clinton claimed that the Reagans started a ‘national conversation’ about HIV/AIDS, the backlash was swift. As anyone remotely familiar with American history knows, the opposite is true: Ronald didn’t say the word ‘AIDS’ in public until 1985, after over 10,000 Americans had died. Within hours Clinton said she ‘misspoke’ before issuing a more extensive apology the next day, but for a brief moment her attempt to rewrite history catapulted HIV/AIDS into main-stream political discourse. In doing so, she prompted vital questions of how we remember the recent past.

In the artworld such questions have preoccupied curators for a number of years, and since 2009 a wave of exhibitions has revisited the cultural practices that emerged in direct response to HIV/AIDS. Some, like ACT UP New York: Activism, Art, and the AIDS Crisis, 1987–1993 (2009) at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, in Cambridge, MA, or Why We Fight: Remembering AIDS Activism (2013), at the New York Public Library, have focused specifically on the cultural output of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). Others, from Helen Molesworth’s This Will Have Been: Art, Love, and Politics in the 1980s (Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago/Institute for Contemporary Art Boston, 2012–13) to the New Museum’s NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star (2013), have addressed HIV/AIDS as part of a broader historical survey. Invariably, though, these exhibitions have limited their scope to a specific alignment of people and place: New York City, the mid-1980s to early 1990s, and the downtown queer art scene. That many high-profile artists met premature deaths has rooted the notion of ‘AIDS art’ in this particular historic moment, and a set of usual suspects – Keith Haring, David Wojnarowicz, Felix Gonzalez-Torres – often dominate such shows. The epidemic continues to this day, though, and infection rates among at-risk groups are on the rise. So what impact does the cultural history of ‘AIDS art’ have upon artists today? And what do we mean by ‘AIDS art’ anyway?

In Art AIDS America, opening in July at the Bronx Museum, New York, curators Jonathan David Katz and Rock Hushka continue this work. Most significantly, they feature a number of younger artists including Kia Labeija and Derek Jackson, who show the myriad ways that art can reflect upon the conditions of HIV/AIDS today. After first opening at the Tacoma Art Museum, however, protests erupted over the glaring whiteness of the display: only four out of 92 artists were African American, despite the latter group accounting for 44 percent of new HIV infections each year. In response, curators at the following stop on its national tour – the Zuckerman Museum of Art, in Kennesaw, GA – added eight new artists into the show, produced additional wall texts and curated a subexhibition, Art AIDS Atlanta, that chronicled the work of local activist groups. Museum exhibitions have long been a flashpoint for activist interventions, given their power to shape the broader cultural meanings of HIV/AIDS. This tension reflects the semantic instability of AIDS itself: as a term for a broad (and contentious) list of opportunistic infections, it defers signification. Instead, AIDS provides an empty signifier in which affected parties can stake – and visualise – their own individual claims to meaning. Since HIV is symptomless and one can be diagnosed with AIDS by only a low T-cell count, visual art is the ideal site for thrashing out meanings of an otherwise invisible disease.

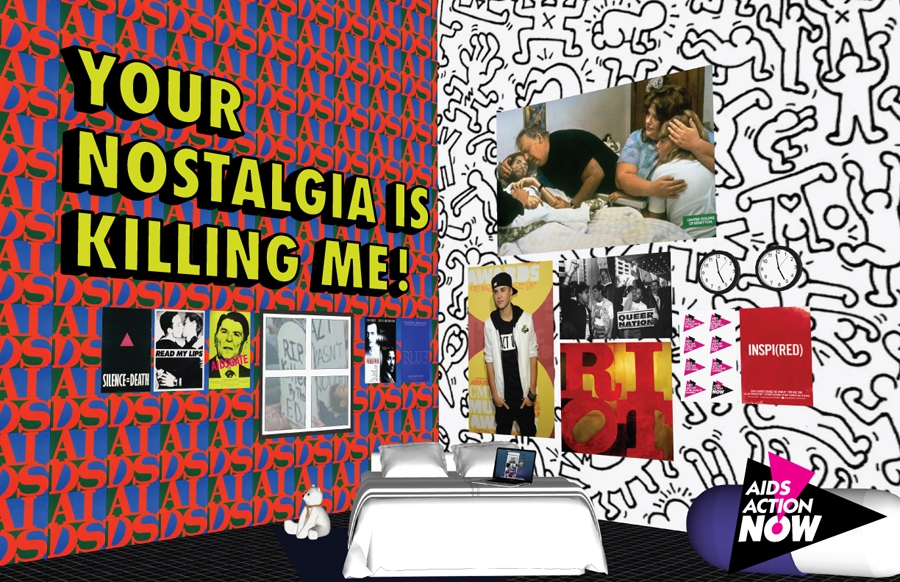

In short, AIDS means nothing, so to pinpoint the meaning of ‘AIDS art’ is a virtually impossible task. Instead, its contingent meanings produce a diverse array of practices that articulate responses to it. Although the body and bodily fluids certainly recur – in Ron Athey’s performances, for example, or Andres Serrano’s early prints – their prevalence is hardly enough to form a definitive aesthetic trope. In fact, ‘AIDS art’ is best defined by a critical rather than aesthetic sensibility. In Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me (2013), for example, Vincent Chevalier and Ian Bradley-Perrin critique the use of activist aesthetics as a vector for cultural capital online; although their poster may mimic early ‘AIDS art’, their caustic irony makes the critical gesture of Your Nostalgia resolutely clear.

To work through the meanings of AIDS, then, required and requires intensive critical labour. This is perhaps best captured by Douglas Crimp’s special edited issue of October, “AIDS: Cultural Analysis, Cultural Activism” (1987), in which both artists and critics theorised what forms activism might take in the cultural sphere. Today, this same work requires young artists to extend their scope beyond the socio-political effects of the epidemic: now, to critically engage with HIV/AIDS means also grappling with its histories. To do so requires a degree of self-reflexivity, and an interrogation of the ‘AIDS art’ canon that bears so heavily on cultural production today.

This article was first published in the Summer 2016 issue of ArtReview.