Our editors on the exhibitions they’re looking forward to this month, from Veronica Ryan and Aki Sasamoto to EVA International and Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Veronica Ryan: Unruly Objects

Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, 22 August 2025–11 January 2026

In the late 1950s, the Turner Prize-winning artist Veronica Ryan moved with her parents from the Caribbean island of Montserrat to the UK, as part of a wave of migrants known as the Windrush generation. In 2021, Ryan created a monument in Hackney Central, East London, to honour these migrants, who faced not only discrimination upon arrival but also, in many cases, wrongful detainment and deportation decades after. Her monument consists of three large sculptures of fruits associated with the Caribbean – a spiky bronze soursop, a luminously patinated breadfruit and a white marble custard apple – sitting mysteriously on the ground, provoking curiosity and rewarding onlookers with visual plentitude. This type of intrigue and uncanniness is characteristic of Ryan’s recuperation- and craft-centred work, four decades of which have been brought together in Unruly Objects, the artist’s first major survey. Forgoing pedestals, Ryan opts instead for vaguely culinary arrangements. In Infection VII (Punnet 1) (2020) an altar-like tower of mushroom boxes sits on a yellow doily. In Collective Moments V (2022), plastic bags wadded into an onion-shaped ball are bound in a coral-coloured hairnet and placed inside a plaster bowl. In Sweet Dreams are Made of These (2021), glazed ceramic cocoa beans are piled on a round jute mat, like ingredients for a recipe that may be generations old – or that may not yet exist. The show is dedicated to her late mother, who taught her how to sew, knit and make the most of meagre resources. Jenny Wu

13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: Séance: Technology of the Spirit

Various venues, 26 August–23 November

Hello, dead ones? Are you still here? Probably not… What’s gone is gone and all that. In any case, let’s hope there will indeed be some actual presence at the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale, because, as its title Séance: Technology of the Spirit suggests, it’ll be having a crack at reanimating the spirit-seeking ritual. Except (just) as a tool for artistic inquiry. An attempt at probing what lies beyond the visible, the rational and ‘the now’. Spanning visual art and cinema, and with a (hopefully appropriate) dosage of psychoanalysis, mysticism and media theory, the biennale draws on ‘alternative technologies’ to counter capitalist modernity. Artists and thinkers from across geographies (including Angela Su, Hsu Chia-Wei, Karrabing Film Collective, Mike Kelley, Sky Hopinka and Susanne Treister) look to occult traditions and spirit media not to escape reality, but to reconfigure it – summoning histories of resistance and entanglement between the living and the dead. Responding to a time of psychic dislocation and digital hyperproduction, this ‘exhibition-as-séance’ promises to tap into the political potential of the immaterial and invisible. Think of it like a haunted interface. Whatever that might mean. Here, mysticism becomes a method – a way of taking a sideways glimpse into a world otherwise ruptured and suppressed by empire, patriarchy and the capitalist market. Will this biennale reconnect us with our lost spirits, or will it just be another parlour trick? Fi Churchman

41st EVA International: It Takes a Village

Various venues, Limerick, 29 August–26 October

Villages were the product of the Neolithic Revolution, tools in the collectivisation of food production from hunter-gatherer to agriculture; their purpose a radical realisation that early humans might survive better exploiting resources as part of a larger whole than as competitive individuals. The Hungarian curator Eszter Szakács has taken the village as her modus operandi to programme Eva, the Irish biennial based in Limerick (which hasn’t been a village since around 812 AD), centring collaborative work and artist collectives (plus one collective of collectives). If this is reminiscent of Indonesia group ruangrupa’s much troubled approach to their documeta in 2022, then perhaps Szakács will benefit from the much smaller size of Eva. ‘It takes a village to raise a baby’ the phrase goes, though it might add ‘but a city is probably too much’. Highlights include Éireann and I, an archive of Black migration to Ireland, and Family Connection, a Curaçao and Dutch-based group whose work addresses Caribbean carnival and vernacular culture. Oliver Basciano

Aki Sasamoto’s Life Laboratory

Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, 23 August–24 November

Imagine a barstool philosopher giving a meandering, life-spanning lecture. Then imagine it animated and illustrated by a room that resembles the ramshackle, multipurpose kitted-out cottage of Buster Keaton’s short film The Scarecrow (1920), where a record player becomes an oven, the bed a piano, and the salt and pepper are passed via an elaborate system of strings and pullies. Now, if you’re keeping up, you have an inkling of Aki Sasamoto’s performance-installations that reorder your sense of logic and possibility. Sounding Lines, her 2024 project made for Para Site in Hong Kong, weaves together ideas on the behaviour of wave particles into a meditation on relationships. Oversized fishing lures hang among a web of elongated metal springs: one with a knife as its body, another with a whisk dangling from the bottom. As Sasamoto speaks on wave harmonics and draws elaborate, esoteric diagrams, it becomes clear each of these lures represents a person from her life. Navigating the waves, Sasamoto asks, ‘What is the depth of our relationships?’ The Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo is taking on the task of staging a mid-career retrospective, appropriately framed as a ‘life laboratory’, gathering together videos, models and diagrams that document such performances from the past twenty years, while four installations – including Sounding Lines – will be set up to hold live performances throughout the exhibition. Chris Fite-Wassilak

Survival Kit 16: House of See-More

Creative City Grīziņdārzs, Riga, 30 August–28 September

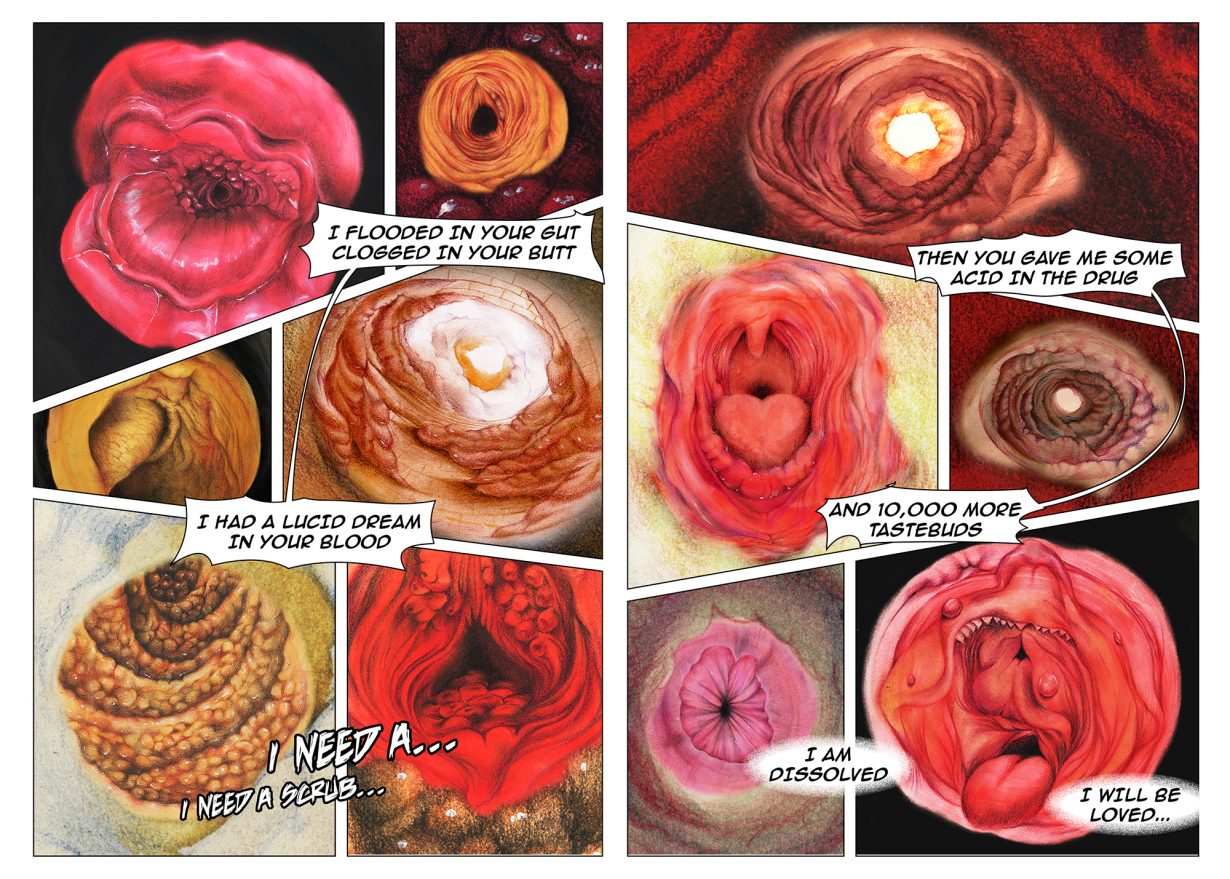

Curated by Michał Grzegorzek and the art collective Slavs and Tatars, the sixteenth edition of contemporary art festival Survival Kit takes place in a former knitting factory. The thread, if you will, running through this year’s edition is the ‘the critical state of transnationalism’, read via the ‘flamboyance of the flaming bird’ – the Simurgh, a mythical bird which crops up in Sufi Iranian, Pakistani, Georgian and Armenian literature, among others. So House of See-More will aim to soar across borders while keeping its sense of community and geopolitical humanism tight-knit. Participating artists include Ali Cherri, Edith Karlson, Karol Radziszewski and works by the late Femen co-founder Oksana Shachko. Keep an eye out for Kexin Hao’s irreverent sense of the horror erotic: one comic strip The Tunnel (2024) gives voice to a series of fleshy sphincters; and her Lewd Banquet performance invited guests to dig in, and ignore the ASMR mukbang soundtrack and sticky tracts projected large on the surrounding walls. How much more would you like to see? Alexander Leissle

Sue Kneebone

Art Gallery of South Australia, 1–31 August

You could describe the artist Sue Kneebone as a kind of archaeologist-cum-fabulist. Also a rogue taxonomist, a medicine woman, a scavenger. Excavating Australia’s colonial past, Kneebone dredges up what appears to be the haunted household and medical detritus left by nineteenth-century settlers and recasts these objects, tools, artefacts and photographs into assemblage, bricolage, collage. There’s a gothic-occultist tilt to her work, too, resulting in unsettling, monstrous forms: animal skulls make up the light shades of a chandelier (Neat Drop, 2014); silver serving trays present pairs of taxidermy pigeon wings that rest against concrete-cast decanters (Spurious Nature, 2018); settler portraits become feral with human-animal hybrid sitters, posing like the emissaries of a repressed colonial consciousness (A Cautionary Tale of Overconfidence, 2010). Kneebone’s world is at once an alternate reality in which oceans, bones and birds can be trapped in glass bottles (The Ceaseless Tide, 2021), and yet at the same time reveals the violences and hierarchies imposed by colonial settlers on Australia’s occupied Country. There is caustic humour in her work, too: rifles and revolvers often appear in her exhibitions, but these lethal tools are defunct, made up as they are of materials soft and brittle – lace or bone, or both. Works from her more-than two-decade career will be on view at Art Gallery of South Australia – a splicing together of the grotesque and the decorative, human and animal, natural landscape and the absurdity of colonial rationalism, and dead things reborn. Fi Churchman

Bagus Pandega: Sumber Alam

Kunsthalle Basel, 28 August–15 November

Nutmeg and nickel are two key commodities of Indonesia’s sumber alam, or ‘natural resources’ in local idiom, which are subjected to extraction by both domestic and foreign, as well as colonial, companies. They’re also the subject of Indonesian artist Bagus Pandega’s latest research trip to the island of Sulawesi. Indigenous to the nearby ‘spice islands’ of Maluku, nutmeg was a primary export of the colonial spice trade and the driving factor behind the Dutch East India Company’s 1621 massacre of Maluku’s islanders; nickel ores, of which Indonesia holds the world’s largest reserves – predominantly on Sulawesi – are one of today’s most sought after materials as a key ingredient of EV batteries. Pandega’s work explores the country’s relationship with its natural resources and the environmental impacts of their extraction, often treating ‘inert’ raw materials as mobilising agents and equipping them with kinetic forces. The series Artificial Green by Nature Green (2019–), made in collaboration with Japanese artist Kei Imazu, sees machine arms paint and erase views of a rainforest on an unstretched canvas; the machine’s jerky movements are powered by the biofeedback of an adjacent oil palm – another cash crop whose plantations have been the major cause of deforestation in Indonesia since the turn of the twenty-first century. In Fabric of the Earth (2025), mud collected from the sites of the Sidoarjo mudflow disaster (itself caused by natural gas extraction) is fed into a 3D-printer, and then shaped into the miniature village houses that were crushed by the mudflow. At Kunsthalle Basel (and concurrently at New York’s Swiss Institute), Pandega will present new commissions revolving around nickel, EV batteries and how they influence the subculture of Sulawesi drag racing. Yuwen Jiang

Bienal das Amazônias: Verde-distância

Various venues, Belém, 29 August–30 September

In Benedicto Monteiro’s 1971 book Verde Vagomundo, a military man returns to his Amazonian village to find that his family and neighbours have slowly become alienated from their environment: the sensorial and animist ties that linked daily life and their very being to the rivers that flowed through the forest, to the trees that stretch up to the skies. Taking the late Pará writer’s idea of ‘green distance’ as her guiding principle, Manuela Moscoso, curator of the Bienal das Amazonas’s second edition, is looking at artists whose works are integrated in their geographical, geological and ecological surroundings. The big names of Brazilian Indigenous art are here, including Joseca Yanomami and the late Jaider Esbell, but Moscoso also brings in 74 artists from across South America, including Mali Salazar, a Peruvian former police officer who shook off what the artist describes as a the ‘indoctrination’ of the old profession to paint and learn to climb, imagining the Andean mountains that inform the work as ‘sites of care’. Likewise Lucía Pizzani’s ceramics tap histories of ecofeminism and her personal experience of environmental activism in her native Venezuela; while Bolivian artist Andrés Pereira Paz’s textiles link the raw fibre of their production to their use-value in circulating cultural mythologies and identities. Oliver Basciano

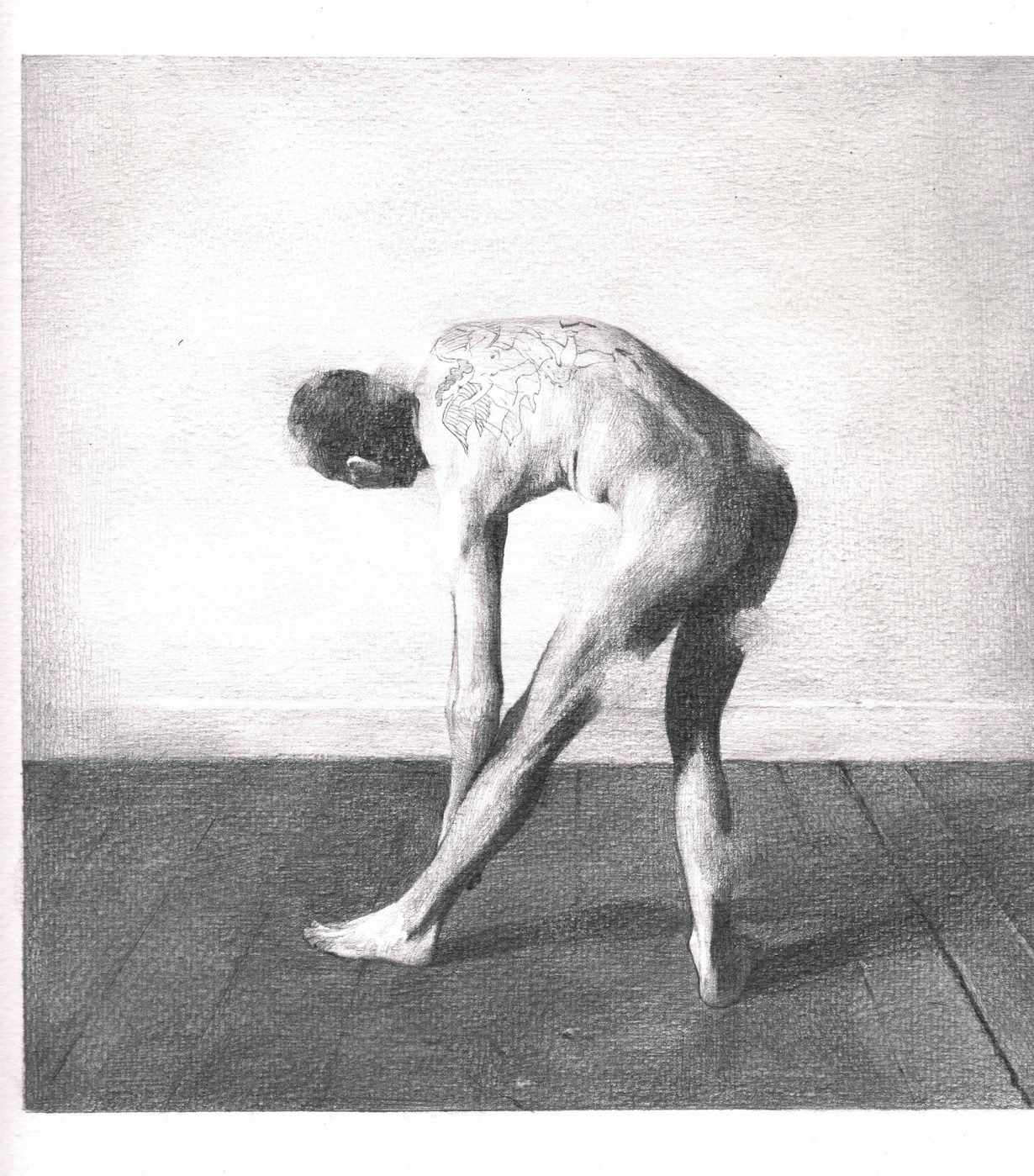

Kang Seung Lee, Candice Lin: Not I, not I, but the wind that blows through me

Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, 27 August–5 October

Given their thematic affinities, I wonder why a paired show of work by Korean artist Kang Seung Lee and the American Candice Lin hasn’t already happened. Both artists combine archival materials with a range of organic matters in works that explore the biopolitics of sexuality and disease. Although you wouldn’t know it from first glance. Lee’s wood-panel folios and paper sculptures shaped like animal hides are, in the simplest sense, immaculate objects, their eulogy to the AIDS crisis often comprising delicate graphite drawings or pieces of artisan sambe cloth embroidered with 24k-gold threads. The occasional snippets of graphic contents – photographs of leather straps, aging skins, genitalia – appear ceremonial, meticulously staged like objects in a museum collection. Whereas Lin’s installed arrangements – including, but not limited to, fermented plants, intoxicating indigo ink, animal lards and piss – capture the mystical and the phantasmagoric nature of the knowledge and desires supressed by colonial forces and biopolitics. The exhibition’s title, too, is taken from a poem by English writer D.H. Lawrence, who himself did much to advance our understanding of sexuality and our evolving relationship with – and alienation from – the physical world. Yuwen Jiang

Adam Unparadis’d

Francis Irv, New York, through 23 Aug

At Francis Irv, there is a shadow box containing around 100 matchbooks collected and arranged by Rose Salane, an artist known for acquiring materials from estate sales and liquidations. If we are to trust the work’s title, Brooke Astor’s Son’s Matchbook Collection (2025), then these curios, which bear the insignias of hotels, airlines and high-end restaurants, belonged to a certain Anthony D. Marshall (1924–2014), who in 2009 was convicted of first-degree grand larceny for tampering with the finances of his mother, the prominent New York philanthropist and socialite Brooke Astor (1902–2007). That Marshall’s own personal effects are now encased above a scattering of large, boiled cow bones on the gallery floor – an installation by Carissa Rodriguez – suggests something of a memento mori with an aftertaste of karma. These are fitting inclusions in a group exhibition styled as a murder mystery, one that involves – we are told in a short, oblique press release – ‘a grand fall from grace’. Jenny Wu