Our editors on the exhibitions they’re looking forward to this month, from Arpita Singh in London to the TarraWarra Biennial

Guillermo Kuitca: Kuitca 86

Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires, 14 March–16 June

In 1982, aged twenty-one, Argentinian artist Guillermo Kuitca had already been making and showing for almost a decade (he had his first exhibition aged thirteen) but a trip to see a performance by the German choreographer and dancer Pina Bausch at a theatre in Buenos Aires threw him off course. He was mesmerised by how Bausch was able to seemingly expand and contract the space of the stage through the simplest of gestures. Geography, mental space, the border between the personal and the public – these became Kuitca’s overwhelming preoccupations. This exhibition (named after the year the last of three bodies of work on show was made) is a portrait of a radical reformation in the artist’s practice. His 1982 painting Nadie olvida nada (No one forgets anything) features a minimalist scene of barely-described figures – some in couples, others on their own, with their backs to the viewer – heading to a grey monochrome. The viewer is left to fill in the blanks, conjuring each of us as the architects of our own imagination. A single bed is just about discernable, the introduction of what would be a reoccurring motif for the artist. The beds are there too in El Mar Dulce (The Sweet Sea) (1984–87); a series of paintings of theatre sets, which as the title suggests, also imagines the theatrical space as a waterway (specifically el Rio de la Plata, the waterway by which Kuitca’s Ukrainian Jewish grandparents arrived in Argentina around the turn of the century); and in Siete últimas canciones (Seven Last Songs) (1986), blue, melancholic paintings of desolate rooms in which the beds stand empty and chairs are overturned. ‘The story, in the anecdotal sense, had been erased,’ Kuitca explained, ‘but what was left was a strong sense that we see a scene in which something has already happened.’ Oliver Basciano

Eimear Walshe: Mixed Messages from the Irish Republic

Chapter, Cardiff, through 25 May

Irish history, the artist Eimear Walshe told ArtReview in a 2024 interview, is one of ‘colonialism and eviction’, through which ‘generations endured the extremes of terror, despair, dispossession, betrayal and ostracisation’. Indeed, Walshe (who works predominantly in video) has long circled the Irish land, searching for an adequate register to address it. There’s Land Cruiser (2022), which takes a cruising hookup in a park as the right time to talk about Irish law, rent controls and how they relate to legacies of British colonial rule. Or, more plainly, there’s Walshe’s lecture/mockumentary The Land Question (2020): “The way I see it, there’s one, and only one, land question: where the fuck am I supposed to have sex!?” But it’s not all horny historicism. Among the ‘mixed messages’ at Chapter in Cardiff will be Romantic Ireland (2024), Walshe’s contribution to the Irish Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale. The multichannel video installation, soundtracked by an opera and displayed among a network of walls built from mud and soil, tells a multivalent story. In a libretto, we learn of a man in the 1940s, struggling to die and being absurdly evicted from his crumbling house. Onscreen, we see a pastiche drama of characters – some dressed formally below the neck like Renaissance courtiers, others in casual, distinctly 1980s knitwear, but all with a rubbery-balaclava stretched fast over their faces – coming together or wrestling each other in the mud. For the similarly spring-heeled, an evening of ‘Irish tunes, songs and dance’ inaugurated the exhibition, featuring Walshe and many of their collaborators. Which is a good way to remember that Irish history is also, in Walshe’s words and works, a story of ‘love, duty and dependence on the land, and on shelter and community’. Alexander Leissle

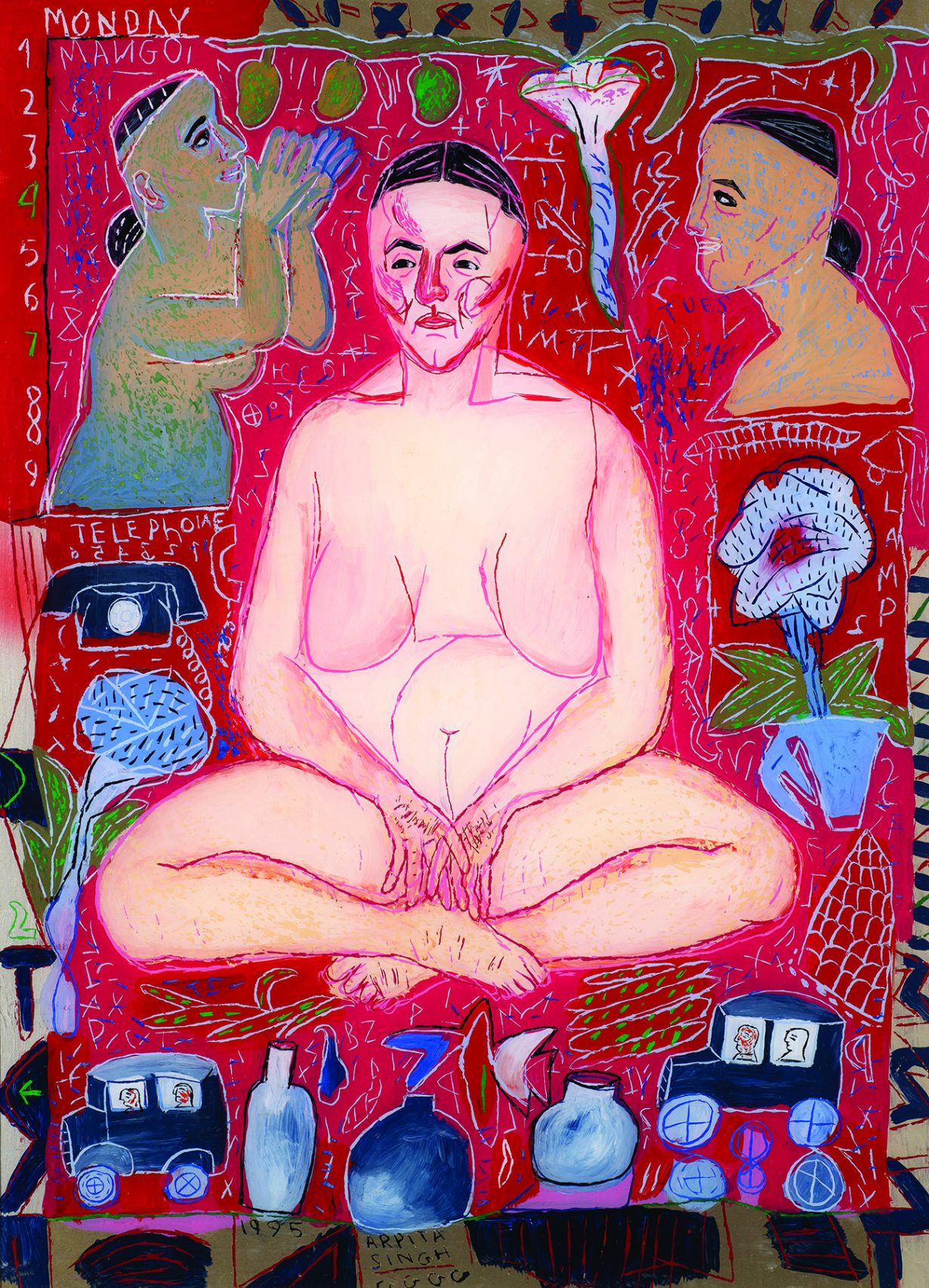

Arpita Singh: Remembering

Serpentine North Gallery, London, 20 March–27 July

A man sits astride a silver aeroplane as he flies towards two angels waiting among the clouds, while a dog floats through the sky nearby in Thirty Six Clouds (2005). There is something of the absurd logic of dreams that guides the densely populated narrative scenes of Arpita Singh, where familiar motifs recur across multiple paintings and the ordinary becomes the extraordinary. Born in West Bengal in 1937, the artist has for six decades experimented with a remarkable, wide-ranging painting practice that has strayed from Surrealism to figuration and even periods of abstraction, in which the teeming energy of her busy, transporting city scenes can be felt in dynamic lines made using monochromatic ink and pens, while the surface of the canvas is at times perforated and broken. A new exhibition at Serpentine in London reflects on the full gamut of her working life, from the 1960s to today, following an appearance in Barbican’s standout The Imaginary Institution of India exhibition last year. Influenced by Indian miniatures, Bengali folk art, modernism and even paper road maps, Singh embraces the contradictions inherent in the combination of these distinct styles, picking and choosing elements from each at will, whether that is the flowered borders that frequently delineate Indian miniature paintings or the vibrant block colours and deities of folk art. Since the 1990s, the artist has also introduced reflections on the collective joy and violence of the female experience, whether through motherhood or sexual encounters, friendship or political solidarity. Mythology meets contemporary life in her roving work, in which an unbridled curiosity about the world around her is ever-present, while the works themselves bear the stains and occasional tears of the rhythmic action of her intensive mark-making over the years. Louise Benson

Jay Payton: A Gentle Kiss to the Anterior Fontanelle

Sea View, Los Angeles, through 29 March

‘This exhibition is a glance into the beginnings of the Homo sapien’, Brooklyn-based artist Jay Payton writes in the press release for his solo show A Gentle Kiss to the Anterior Fontanelle. Suffused with primeval greens and pelagic blues, the abstract paintings displayed here exude a pensive, implosive energy, registering less the grand gestures of a body moving in space than the intense buzzing of a mind lost in thought. Influenced early on by the work of Anselm Kiefer at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia, where he grew up, Payton often layers oil paint with other media – paper, aluminium – on surfaces ranging from canvas to cardboard, to create bryophytic bursts of mottled colour and moody impasto. The title of his exhibition at Sea View references the soft spots on infants’ heads that allow their skull bones to shift as they pass through the birth canal, and some of the paintings there – The Process of Human Embryonic Evolution (all works 2025), When the Water Breaks – reference the science of biological reproduction. Meanwhile, American Sterilization, a wall-based sculptural installation featuring a naked, scowling baby doll framed in barbed wire alongside two airsoft rifles and a bag of fake cash, evokes the carceral system, gun violence and the historical use of forced sterilisation as a tactic of racial subjugation, existential obstacles against which life and its nurturers nevertheless persist. Jenny Wu

Lining Revealed: A Journey Through Folk Wisdom and Contemporary Vision

CHAT Hong Kong, 15 March–13 July

Interests in folk culture and heritage seem to be on the rise across sinophone art scenes. Last summer, Folk in Order opened at Beijing’s Macalline Art Center, in which the curator Wang Huan infused the idea of folk with a kind of alterity, and used it as a critical lens to see the raw realities at the margins of mainstream, late-capitalist urban culture. At Hong Kong’s Centre for Heritage, Arts and Textile (CHAT), the meaning of ‘folk’ shifts to its more benevolent side – more attuned to craftsmanship, artistic sophistication and the idea of heritage in which knowledge and memories are preserved and passed down. Which is understandable given the institution’s own history as a former cotton-spinning mill and its role in safeguarding the legacy of Hong Kong’s textile industry. On view at the show will be a variety of textile-inspired works, weaving together reflections on materiality and communal labour, from Chinese artist He Yongdi’s remake of Cultural Revolution era tubu clothes, to Güneş Terkol’s fabric pastiche made with a community of Indonesian weaving ladies. Also on display will be a vast three-storey high commission, presented by Indonesian artist Ari Bayuaji. This latest iteration of Weaving the Ocean (2020–) will be made from plastic ropes collected from the coast of Bali, in which traditional weaving techniques find afterlife through industrial wastes. Together CHAT’s idea of ‘folk’ is one that guides us through a communal world, in which crafts and community need to be equally taken care of. Yuwen Jiang

TarraWarra Biennial 2025: We Are Eagles

TarraWarra Museum of Art, Wurundjeri Country, Australia, 29 March–20 July

On the 150th anniversary of the colonisation of Australia, Indigenous activist Sir Douglas Nicholls wore a black suit of mourning and, alongside fellow protestors, marched through Sydney in silence. One of the first civil rights protests carried out by Indigenous Australians against the injustices perpetrated against their communities, the Day of Mourning (as it was then dubbed) marked an occasion that saw a collective call for change and for equal rights. During one of the assemblies, Nicholls demanded an end to colonial repression, stating “we do not want chicken-feed … we are not chickens; we are eagles.” Reflecting on the importance of this political movement, We Are Eagles is the title of the ninth TarraWarra Biennial, which hopes to share ‘cross-cultural knowledge and stories through a network of regenerative practice that disrupts colonial temporalities’. Curated by Kimberley Moulton, the biennial brings together twenty-three artists from across the globe whose works relate to one another via themes of ancestral knowledge, connections to land, water and sky, and shared colonial histories. Kamilaroi artist Warraba Weatherall (whose solo exhibition Shadow and Substance opens at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney this month) will present a newly commissioned installation that ‘focuses on the repatriation of intangible cultural property and knowledge systems, exploring their contemporary role in communities’ – part of his ongoing research and practice that interrogates how cultural objects are collected and presented by museums whose foundations were built by colonial systems. Fi Churchman

Weird Hope Engines

Bonnington Gallery, Nottingham, 22 March–10 May

What to do when the present is a boghole of despair? There is an alternative; you just have to envision it, and sometimes (just sometimes) art and games can help. Back in the olden days, before there were any ‘immersive light installations’ or ‘AR goggles’, there were dungeon masters, a set of dice and the good ‘ol imagination. The world of tabletop roleplaying games goes way, waaay beyond chaotic wizards and orcs. Weird Hope Engines, a group show curated by artist David Blandy, curator Rebecca Edwards and writer Jamie Sutcliffe, is about exploring gaming and roleplaying formats as a means of collaborative storytelling and imagining different possibilities, bringing together an international set of eleven artists and game designers, including new media scholar Angela Washko, Malaysian writer Zedeck Siew and Blandy’s own work in the field. For the March 2024 issue of ArtReview, Sutcliffe and Blandy created a roleplaying game they gave the same title as this exhibition (subtitled ‘A Choking Dust… Red, Clotted and Awful’. In the game, humanity had wrecked Earth and the player’s job is to navigate the new strange landscapes and myths as they settle on Mars. In that vein (and drawing on their symposium ‘Areas of Effect’ at arebyte, London, also staged last March), they’re now putting those ‘weird hope enginges’ into practice: the gallery will hold a set of new games and installations, where visitors are invited to look, play and reconfigure their reality. Chris Fite-Wassilak

Forum: Water Assemblies

Salt Beyoğlu, Istanbul, through 31 December

Once while walking in a remote island in the middle of the Atlantic, I came across a former bottled water factory in ruins. A pipe protruding directly from the earth gushed with slightly fizzy, mineral-rich water. At the time I wished I had more bottles to carry it away with me, but most of all I wanted to hold onto the memory of this strange collision of a manmade infrastructure of extraction and a natural resource so integral to our survival that it governs everything about how we live. It was as if I had all but dreamed up this abandoned oasis in the middle of the ocean. Since the beginning of time, the search for water has had the power to shape economies and ecosystems, and to both unite and divide communities. Water starts wars and has been used as a weapon, such as the deliberate contamination of aquifers in Palestine during the recent Gaza war, which has rendered 97 percent of the water undrinkable. Water Assemblies, a new research forum at Salt Beyoğlu in Istanbul, is the first of a new annual series of collaborative investigations into various spatial practices. Water will be explored at the gallery throughout this year as both a material and a metaphor, in relation to geographies, infrastructures, language and imagination, by creative practitioners including Gökçen Erkılıç, Ezgi Hamzaçebi and Merve Bedir. Accompanied by roundtable meetings, film screenings, public discussions and performances, a new publication will be released at the end of the project. Looking outwards from Istanbul’s position on the water towards other shores, the forum evokes water as both a local and global force, from a slow drip to a fast-flowing stream, a bottle of mineral water to a crashing wave. Louise Benson

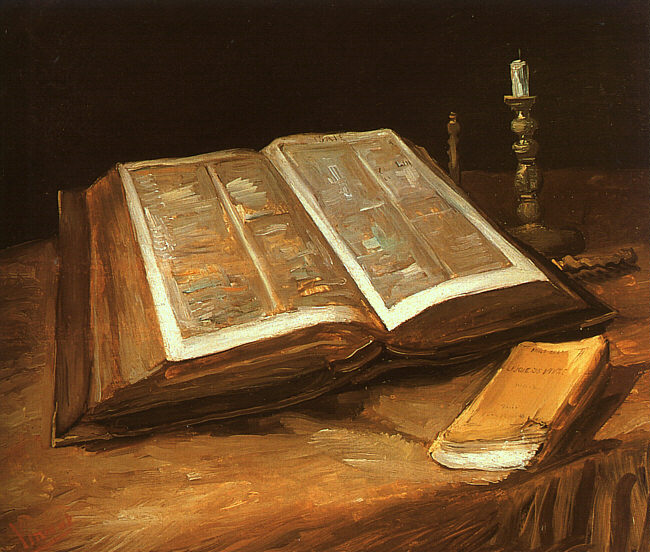

Ben Lewis: Word of God

BBC Radio 4, through 19 March

British documentary filmmaker, writer, scandal-sniffer and art critic Ben Lewis has made a career out of probing the mechanisms that make the international artworld tick. His findings range from the banal to the bizarre, greased along by heavy doses of humanity, irony and a certain type of morbid wonder. His 2003 TV series Art Safari picked apart the stuff and nonsense of conceptual art and relational aesthetics and the artists those ‘movements’ made rich. His book, The Last Leonardo (2019), picked apart the provenance and ‘miraculous’ trajectory to market of Salvator Mundi (c.1499–1510) in a feat of artistic detective work that might have come out of a G. K. Chesterton novel. Now he’s back with a podcast series that dives into the murky foundations of the Museum of the Bible in Washington D.C. (which offers attractions such as ‘Explore! A Virtual Reality Tour of the Lands of the Bible!’), established by the evangelical billionaire Green family in 2017 to collect ‘biblical’ artefacts and drive home the notion that the good book is the central pillar of American-ness – whatever that is. The Museum of the Bible is like some modern-day crusade, and we all know how the original ones ended. Frauds, looters, charlatans, criminals, scandals, fake Dead Sea scrolls, hundreds of cuneiform tablets smuggled out of Iraq and into Hobby Lobby craft stores (owned by the Greens), religious obsessives and God: this one has it all. Nirmala Devi

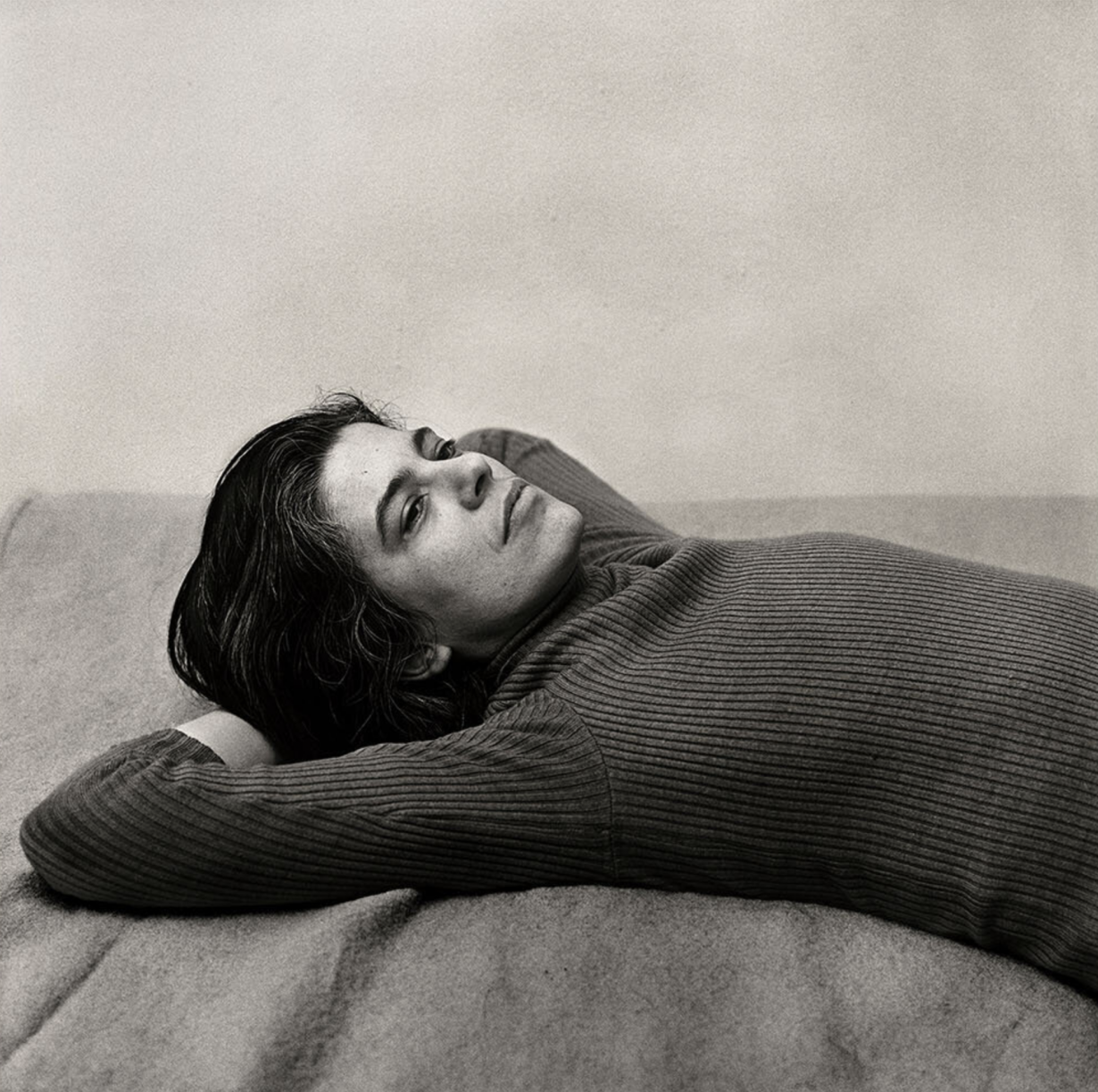

Susan Sontag: Seeing and Being Seen

Bundeskunsthalle Bonn, 14 March – 28 September

Critic, author, filmmaker, activist, feminist and all-round public intellectual Susan Sontag spent a career considering the unavoidable power of images in the age of mass media. A dynamic figure in the avant-garde circles of New York in the 1960s, Sontag’s criticism took on everything from pop culture to literature to European New Wave Cinema to the American underground film and performance scenes, in a style that probed the moral, ethical and political demands of artworks on their audience. Many of Sontag’s texts remain touchstones of contemporary cultural criticism, and epitomise Sontag’s relentless engagement with flashpoint issues in culture; from the 1963 Notes on Camp’s pioneering consideration of the politics of bad taste, to the probing of the cultural panic around the AIDS crisis in AIDS and its Metaphors (1989), and the reflection on the morality of seeing images of war and disaster in 2003’s Regarding the Pain of Others. An exhibition of artworks based on Sontag’s life and critical ideas, Seeing and Being Seen, frames Sontag’s critical ideas through the artists and images that she attended throughout her career. Questions of photography’s realism and truth-telling account for the presence of early masters such as Eugène Atget, Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange; the aesthetics of gay culture are represented in the work of James Bidgood, Peter Hujar and Andy Warhol; while the ethics of photography as documentary, or as propaganda, are embodied in the epoch-defining Vietnam War photography of Nick Út and the Nazi-glorifying work of Leni Riefenstahl. Alongside works by these figures (and over 30 others) are film extracts from works by Warhol, Jack Smith, Ingmar Bergman and Sontag herself. JJ Charlesworth