Matthew Perry, Chandler Bing, Egon Schiele and Me

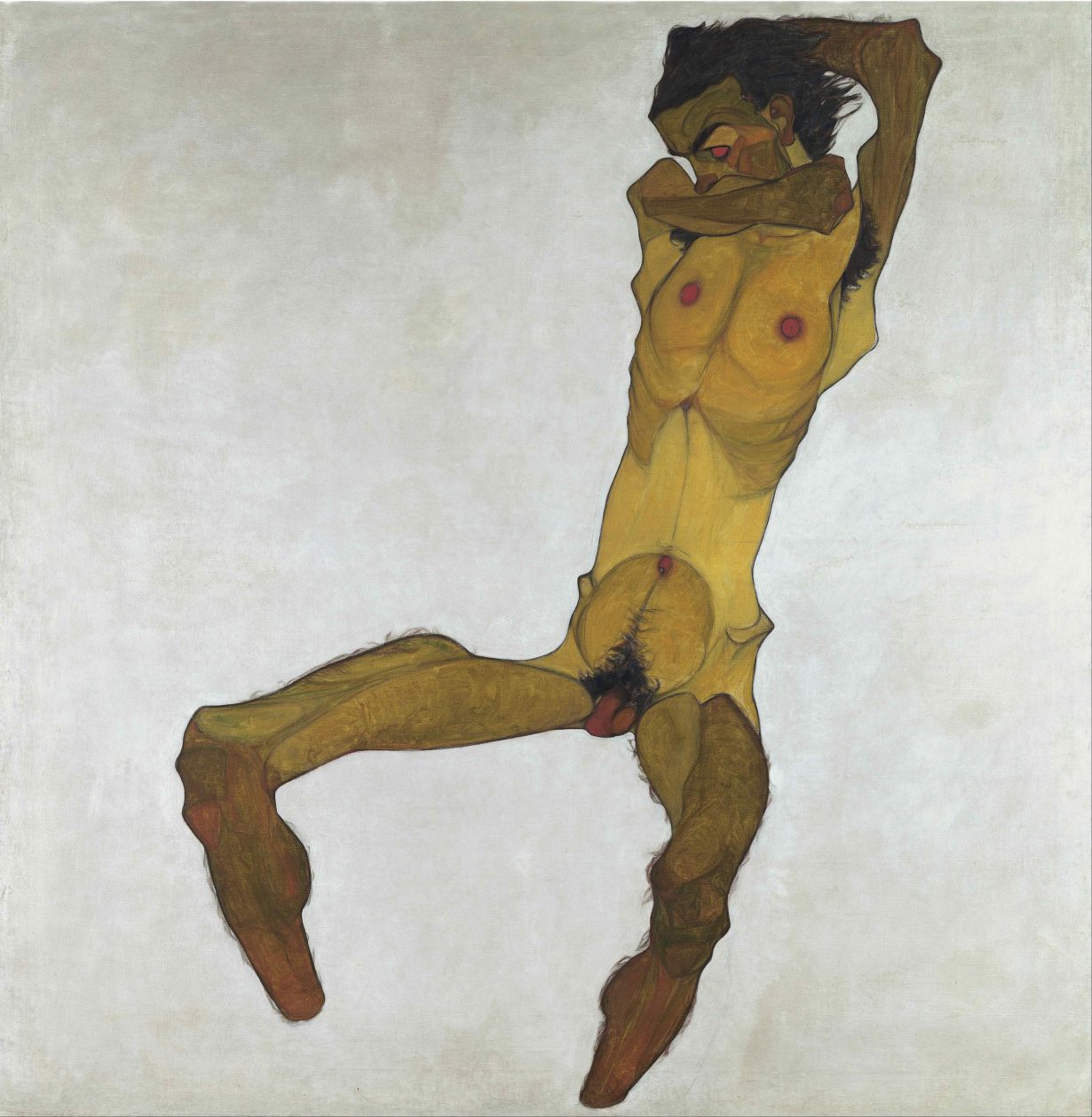

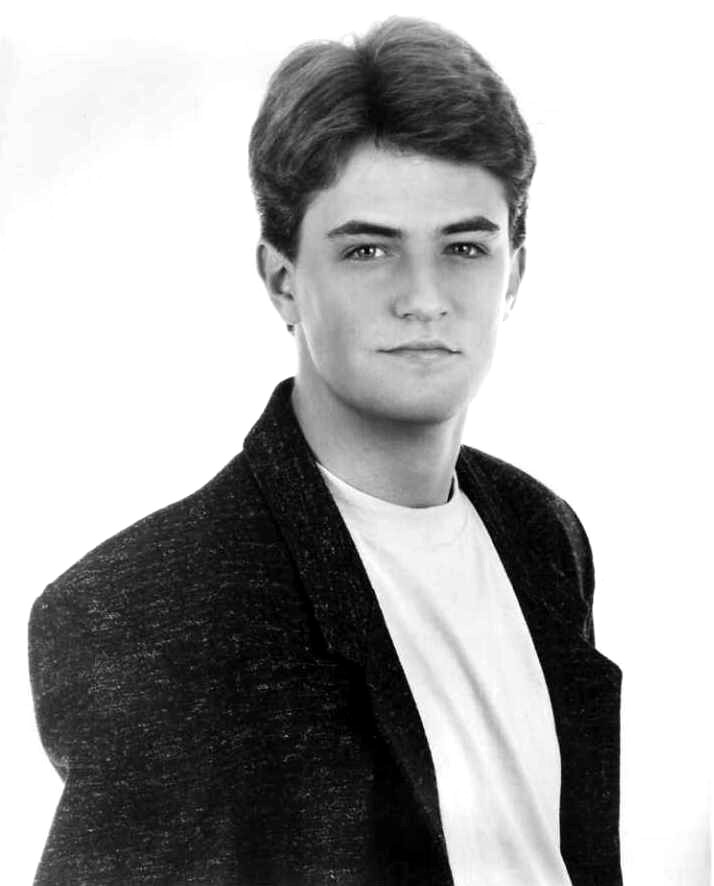

If you squint, Egon Schiele’s Seated Male Nude (Self Portrait) (1910) looks a bit like Matthew Perry. The shock of brown hair, the skinny build, a sarcastic eyebrow raised. A week after Perry’s death, I had noticed this on Instagram, when one reel after another conflated the two images: a clip of Chandler Bing on Friends followed by an extract from a video on Schiele from the channel The Art Hole. I had a framed poster of Seated Male Nude in my university bedroom, next to a Friends boxset I would watch compulsively as I was overwhelmed by intrusive thoughts from undiagnosed OCD. When I look at these two bodies almost a century apart, I see two manifestations of hegemonic masculinity, what Toby Miller in his 2002 book Sportsex defines as ‘Western European and North American white male sexuality [which is] isomorphic with power’. This patriarchal philosophy has presented me with an incredibly narrow view of what the ideal male form ‘should’ look like: a broad chest, well-defined abdominal muscles and visible biceps – for a start. Looking back, everything from an incoming apocalypse that would leave me destitute and running for my life, to my ongoing attempts to get a six pack seems epitomised by these two figures, Chandler and the seated male. Schiele’sshaky lines remind me of quivering, worried hands after panic attacks, and I see my flurries of intense exercise followed by collapse mirrored in the way Perry’s weight shifts across ten years onscreen. Perry’s recent death and the Instagram algorithm resurfacing Schiele’s work to my consciousness returned me to grappling with male anxiety – over body, power, control and why, as a society, we look at men this way.

In Seated Male Nude, painted by a 20-year-old Schiele, there’s no chair in the background. The figure’s emaciated hips hover in space, as if he has been pushed into a squat by an unsympathetic personal trainer and made to hold it until his glutes scream. His hip bones protrude, his ribs are exposed. This figure would fail to adhere to the twenty-first-century rules of hegemonic masculinity, where the body must be powerful, muscles large, pectorals and abs resplendent in their definition. Gender signifiers are elusive and indefinite: Schiele’s shadowing around the figure’s chest creates curvature like a breast; the mouth and chin are obscured so as to prevent a clear delineation of soft or hard facial features; even the genitals are ill-defined below the clump of pubic hair. Culture, narrative art, and misguided PE teachers have imparted honour and rewarded certain body shapes, while piling shame and failure on others. Looking at this painting on Instagram, surrounded by fitness influencers and Marvel superheroes, I am flushed with anxiety. I feel that the body Schiele painted, twisting himself into different poses before the mirror, is my body: a small, frail thing which fails to achieve the physical or moral integrity expected of ‘proper’ masculinity.

A version of this body anxiety was crudely rendered by Friends writers in reaction to Perry’s dramatic weight fluctuations, caused by his struggle with substance abuse. In his memoir Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing (2022), Perry described how the nature of his addiction can be charted throughout the run of the show: ‘When I’m carrying weight, it’s alcohol; when I’m skinny, it’s pills’. Two early episodes show the anxieties of both actor and character. In season two, Chandler worries about his weight gain. When Monica offers to work out with him, he agrees, then adds ‘but if I put on spandex and my boobs are bigger than yours I’m going home’. A season later, Perry is thin, swallowed by the overcoat he wears, and now the plot revolves around his character giving up smoking, now a dramatically ironic nod to his struggles. In a later ABC interview, Perry reflected on his weight loss in Friends: ‘I was 155 pounds, going on for 123… that’s a guy who’s out of control, he’s going through too much.’ We see the anxieties of actor and character collapse into one another. Both instances reveal a preoccupation with appearing fit, and importantly, whether underweight or overweight, a commitment never to appear vulnerable or lacking control. Men today still feel they must adhere to those principles of hegemonic masculinity that are ‘isomorphic with power’ and that this should be represented in their body. Even further, men experience a kind of meta shame: they are told not to be vain ‘like women’, that a fixation on shape and appearance is to be ridiculed (as Perry must through Chandler in Friends). So men suffer but cannot admit it, society does not validate this suffering, and thus the a closed loop of anxiety is set in motion.

In my twenties, when everybody else was supposedly feeling indestructible, I was convinced I was going to die. At times I believed my body to be too big: a flabby stomach, a wobbling double chin. At other times, I thought it was too small – skinny arms and visible ribs. In both these bodies – epitomised by Perry and Schiele – I saw a vulnerability to death, to illness, and at its most extreme, an inability to run from apocalyptic scenarios I was anxiously convinced would come to pass. Compulsive exercise and the pursuit of that ‘ideal’, matric male form – broad chest, well-defined abdominal muscles, visible biceps – was my way of trying to counter death. But that ideal is unattainable. It hinges on the conviction that we should constantly be striving for a body type that is not only impossible within life’s other obligations, not only temporary and changeable within weeks, but also imaginary. The ‘ideal’ male form is an imagined combination of a set of contradictory features that no one person could ever have all of. The point then becomes not the core muscles to hold you up when running, not the biceps which can lift boxes or get behind punches in times of conflict: the point is the power they represent. For the twenty-first-century man, to be ‘out of control’ as Perry puts it, is to be pitied, feared, avoided. Exercise, diet and the constant analysis and management of our bodies is how we are taught to keep them in check. That is why I still look at those bodies: I see a pain in Perry and Schiele that resonates with me. And to see that anxiety reflected makes me want to push beyond it – to find a salve for my ever fluctuating, five-a-side playing, fitness-chasing, anxiety-ridden, now-30-year-old body. I look at Perry and Schiele and recognise still that a spectrum of bodies exists. This helps me find a way to ignore the shouts of patriarchy’s personal trainer, to know that this body will survive, floating calmly and unimpeded in space.

Lewis Buxton is a writer whose first book, Boy in Various Poses, was published in 2021.