While squabbles over the merits of identity-driven art abound, real world powers in the US are threatening any diversity progress of recent decades

In March this year, Donald Trump signed an executive order titled ‘Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History’, lambasting a ‘corrosive ideology’ that ‘seeks to undermine the remarkable achievements of the United States’. The document singled out one art exhibition in particular for its wokeness. The Shape of Power (whose run completed this month) at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in Washington, DC, gathered historical and contemporary work to demonstrate how sculpture feeds and enforces myths around race. The government, meanwhile, claimed that the show ‘promotes the view that race is not a biological reality but a social construct’. It sure did. Not in a subtle, coded way, either. It was posted on the wall: ‘Race is not a biological fact. Race is a human invention.’ Of course, race also has real consequences. It said that on the wall too. The show was refreshingly frank.

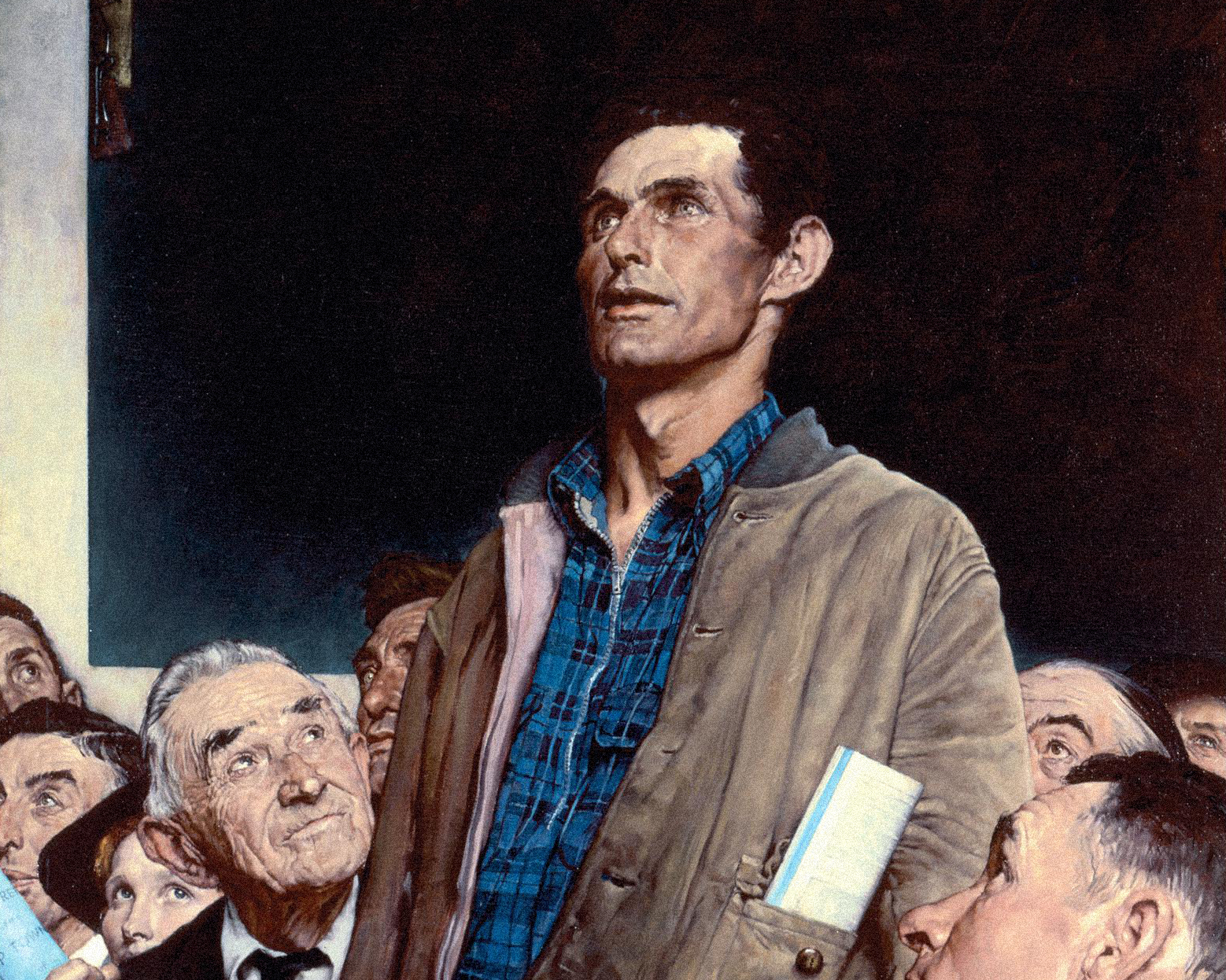

One display featured The Dying Tecumseh, an 1856 marble sculpture depicting the eponymous Native American Shawnee general reclining in extremis. The work is conspicuously white, a neoclassical romance to match the Graeco-Roman ambition infusing Washington’s architecture. The dying warrior is clean and calm, far from the gore of a real battlefield, as if accepting the peace of an inevitable defeat. As an exhibition label noted, The Dying Tecumseh was on view in the Capitol for over a decade, from 1864 to 1878; American lawmakers likely passed it on their way to legislate the end of the frontier and Reconstruction after the Civil War. If this sculpture in some way contributed to white supremacy – the violent smoothing over of the world – then today it testifies to that history.

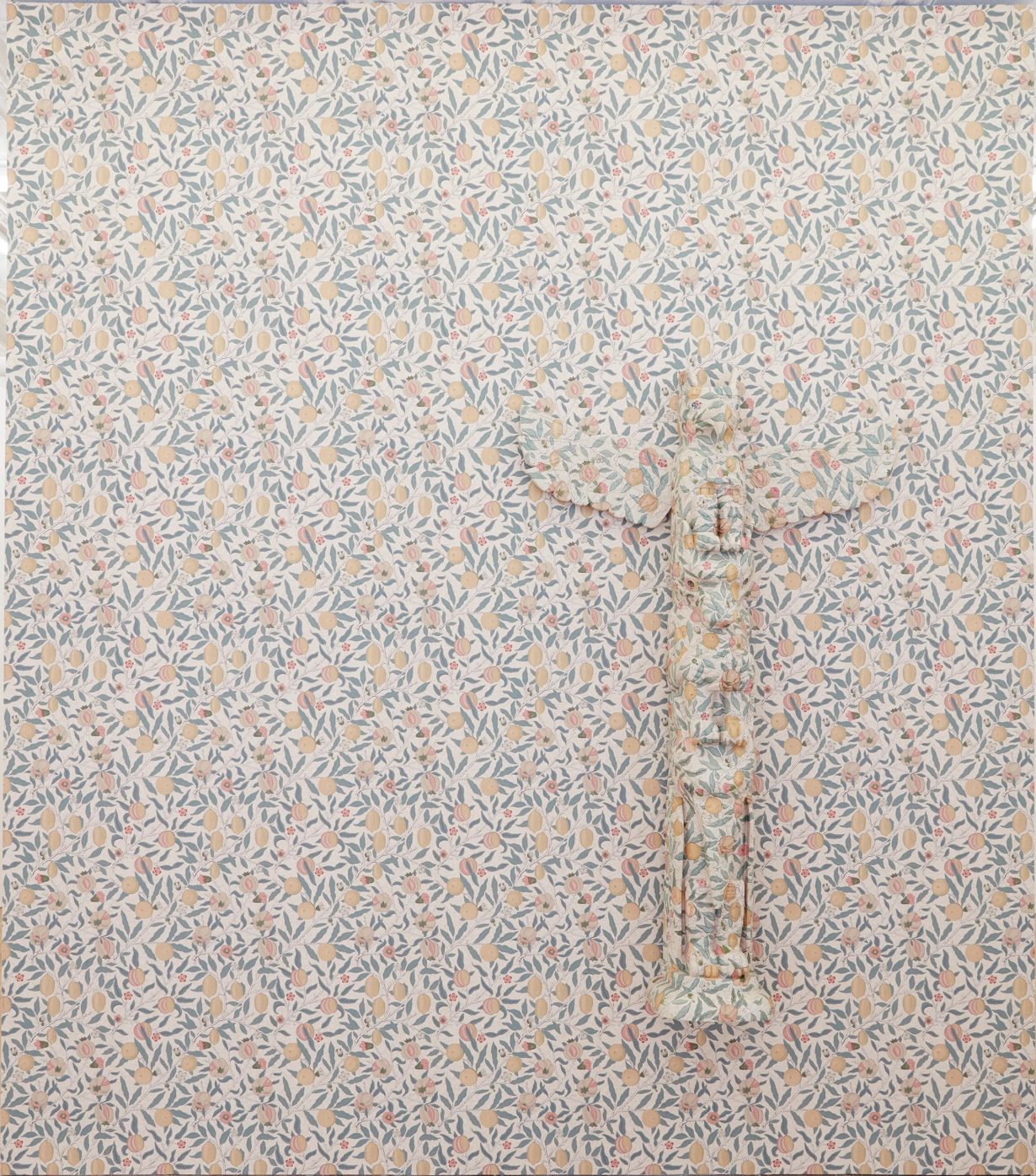

The US art industry is going through a phase of self-censorship, and two of the most prominent cases of artistic repression have been at Smithsonian museums. First, in July, Amy Sherald took her survey off the National Portrait Gallery’s calendar, apparently after the curator suggested buffering her painting of a transgender woman posing as the Statue of Liberty with a condescending amount of explanation. (The incident is included on a White House website listing reasons ‘Trump was right’ about the Smithsonian’s ideological turn.) Then, early in September, Nicholas Galanin, a Lingít and Unangax̂ artist whose work also features in The Shape of Power, pulled out of a symposium related to the show when he discovered it would be held in private – an exclusive audience, no mention on the website and no recordings allowed. On Instagram, he said: ‘My work is only possible because of the ancestors who persisted and refused to be silenced; who continued to carry our culture and pass on that responsibility to me.’

Neither the National Portrait Gallery nor the SAAM forced the artists out. Instead, they introduced conditions on their participation that the artists couldn’t in principle accept. At least in public and as of this writing, the directives from on high have largely been vague and capricious. But nobody wants to be the next target. There have been enough examples made to demonstrate the cost of fighting back. In May, for example, Trump tried to fire Kim Sajet, the National Portrait Gallery’s director. The museum insisted he didn’t have the authority to do so, then Sajet resigned and moved to Wisconsin.

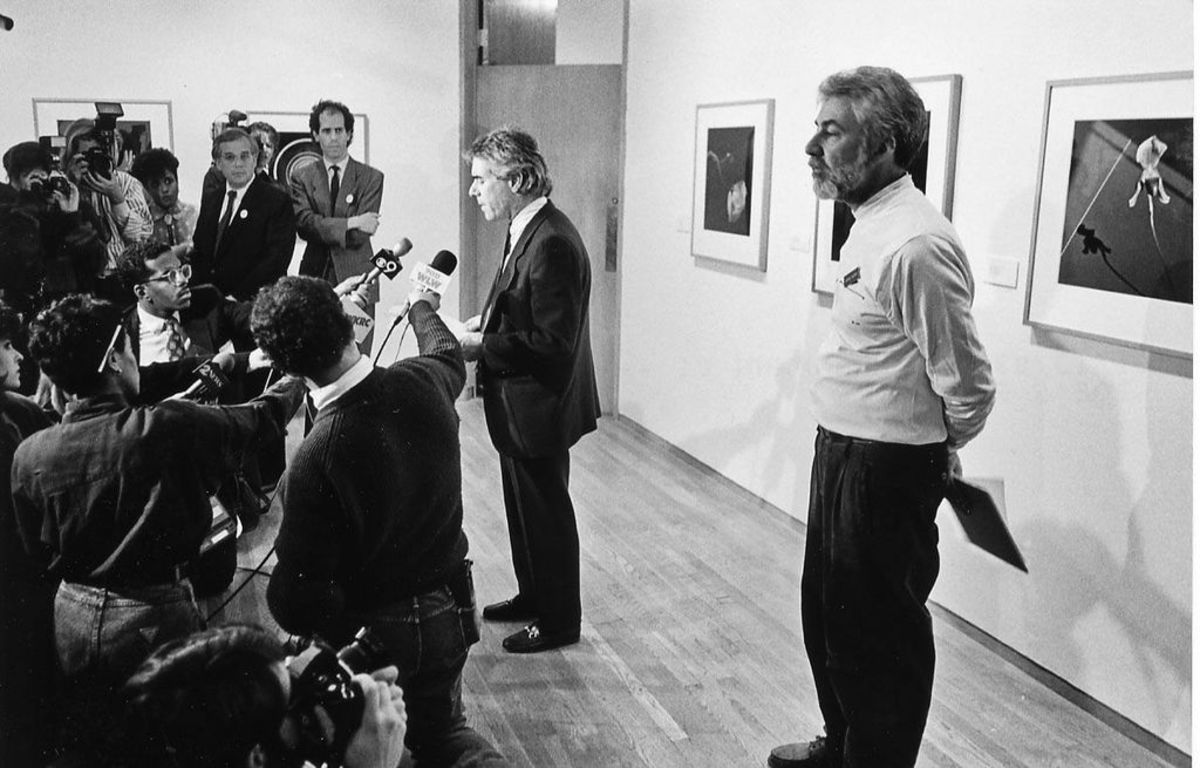

Of course, the US has a long history of culture wars. The days of internet conspiracy hounds pointing out the ‘sperm cell’ in Obama’s presidential portrait are a quaint memory, preceded by the more straightforward tactics of the 1980s and 1990s. Back then, congressmen denounced the work of Robert Mapplethorpe and Ron Athey as pornography on the senate floor. The ordeal of the NEA Four, the performance artists accused of lewdness in the early 90s, led the National Endowment for the Arts to stop funding individual projects. We’re not quite back to the 1960s, with vice squads shutting down underground newspapers and Warhol films for ‘obscenity’. But specific shows and artworks are both on rightwingers’ punch lists and official government websites, and J.D. Vance has promised to go after left-leaning nonprofits like the Ford Foundation, who now fund what the NEA won’t. The message: obey in advance. While this isn’t precise or pervasive enough to be censorship, it’s not exactly free expression either. And it’s incredibly efficient. In return for a few hours’ work on an executive order (or a short ChatGPT prompt), the White House has made progressive institutions squirm for months.

They already had their hackles up. Today, museums are afraid of drawing rightwing ire; yesterday, they feared offending leftwing audiences. Arts groups and institutional coalitions have asserted the importance of free expression, and a wave of organised resistance is planned for November. Yet the issue has been muddled, both by overuse as a conservative talking point, and by leftist infighting and fear. Even among artists, not everyone wants free speech. All the while, the stage is set for Trump’s critique of ‘wokeism’ to accomplish a severe retrenchment of the much–maligned trend in identity-driven art.

Much of this soul-searching among progressives began in earnest after Trump’s 2016 win, then further ignited by the Black Lives Matter movements and the COVID lockdowns. In 2017, white artists like Sam Durant and Dana Schutz found themselves chastised for work about nonwhite tragedies, and curators fretted that Philip Guston’s ambivalent Ku Klux Klan paintings needed ‘the proper context’. In the last two years, the war in Gaza, which the UN recently found meets the definition of a genocide, has fractured the art industry, often along surprising lines. This summer, as Republican aids scrutinised the Smithsonian, the Whitney Museum stepped in to cancel a performance by three Palestinian artists organised by its Independent Study Program, then fired its acting director and ‘suspended’ the entire programme.

Each of these cases has been called censorship. It can be tempting to argue that critics of multiculturalism during the 1990s and identity politics during the 2020s share an illiberal spirit with ‘cancel culture’. But that misses the point. The point is that while the artworld both advocates for and cries wolf about deplatforming offensive work, people with political power are making tangible changes that threaten any diversity progress of recent decades, and hungrily eyeing enclaves of free expression.

The Trump government’s efforts to stifle their critics have only escalated since the assassination of rightwing partisan Charlie Kirk on 10 September. Somehow, the family-friendly comedian Jimmy Kimmel became a hero of free speech when Disney seemingly bent to Trumpian pressure and ‘suspended’ his talkshow after relatively benign remarks on the shooting, then returned it to the air a week later. Several others, from a Washington Post opinion columnist to an Office Depot employee, have been fired for expressing disapproval of Kirk’s controversial views. Conservatives who once decried ‘cancel culture’ now cheer ‘consequence culture’ as broadcasters come to heel, alongside universities and law firms. This year, the US dropped two places in the Reporters Without Borders index of press freedom, to 57th in the world. Add all this to a wider downward mobility and precarity, and the price – material and psychic – of operating in public in the United States has grown prohibitively dear.

The case of the Shape of Power symposium points to a trend: public discourse, at public institutions, going underground, into the dark-forest spaces where many artists and intellectuals have already sequestered their true opinions. This month, Collective Courage published an open letter asserting ‘our democratic responsibility to act as guardians of artistic freedom and independent thought’, and committing to ‘resisting external pressures’, endorsed (as of now) by hundreds of cultural organisations and individuals. Very few museums have signed.

The administration has given the Smithsonian until December to start dewokifying. Meanwhile, The Shape of Power did what a serious, prominent show should do: address current events, issues, debates, through a complex yet legible tour of art history. It demonstrated that the concept of race, as it exists in the United States, had to be created – in part as a basis to exclude nonwhite people from the right to free expression. And it showed some of how artists either filled or resisted power’s mould.

MOCA in Los Angeles hasn’t signed the Collective Courage letter either. But their new exhibition, MONUMENTS, opening in October, presents a touchy subject: an exhibition of toppled and removed Confederate monuments. The show has been in the works since Trump’s first term. You can imagine a sensational, blunt-force version of the idea. But the deliberate pace of the show’s development suggests an understanding of how history is actually constructed – with a thousand dying Tecumsehs.

Travis Diehl is a writer and critic living in New York

This article was corrected on 24 September. It previously located Amy Sherald’s withdrawn exhibition at the Hirshhorn.