The videogame, helmed by director Hidetaka Miyazaki (with worldbuilding by George R.R. Martin) taps into a history of pulp and religious art

On its release on 25 February, Elden Ring, the newest game from Japanese developer FromSoftware, helmed by lauded director Hidetaka Miyazaki, began an unstoppable ascent to godhood. Showered with critical praise, with sales figures usually exclusive to mega-franchises like Call of Duty or FIFA, this high-fantasy epic, marked by its dread-laden atmosphere and ruthless difficulty, has in just a couple of weeks attained a legendary status achieved by few games. This isn’t surprising perhaps, given the reputation of the developer’s previous works, namely the highly influential and beloved Dark Souls trilogy (2011-2016), but the critical assent has been something to behold.

And perhaps it was in that flurry of Elden Ring screenshots that drowned my social media feeds with windswept landscapes populated by bizarre monstrosities, that I formed an association between the game and another, more personal online obsession: Boschbot. Its Instagram and Twitter accounts post cropped close-ups of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden Of Earthly Delights (1490-1510) and The Temptation of St Anthony (1501) every few hours (and the results are hypnotic).

Bosch’s surreal, anachronistic paintings are an obvious delight, but it is in this form, where the close crops uncover secrets and create associations between framed subjects that they seem to shine. There’s a vital energy to these unusual details, where chimeras of object and beast gurn at unseen targets, and blithe faces stare at severed hands or bloodied swords with saintly calm. Bosch’s work, more than 500 years after his death, still retains an incredible power, but also a wonderful and much-debated sense of obscurity; was he a grotesque humorist or penitent painter of horrors? A religious progressive or a fanatic?

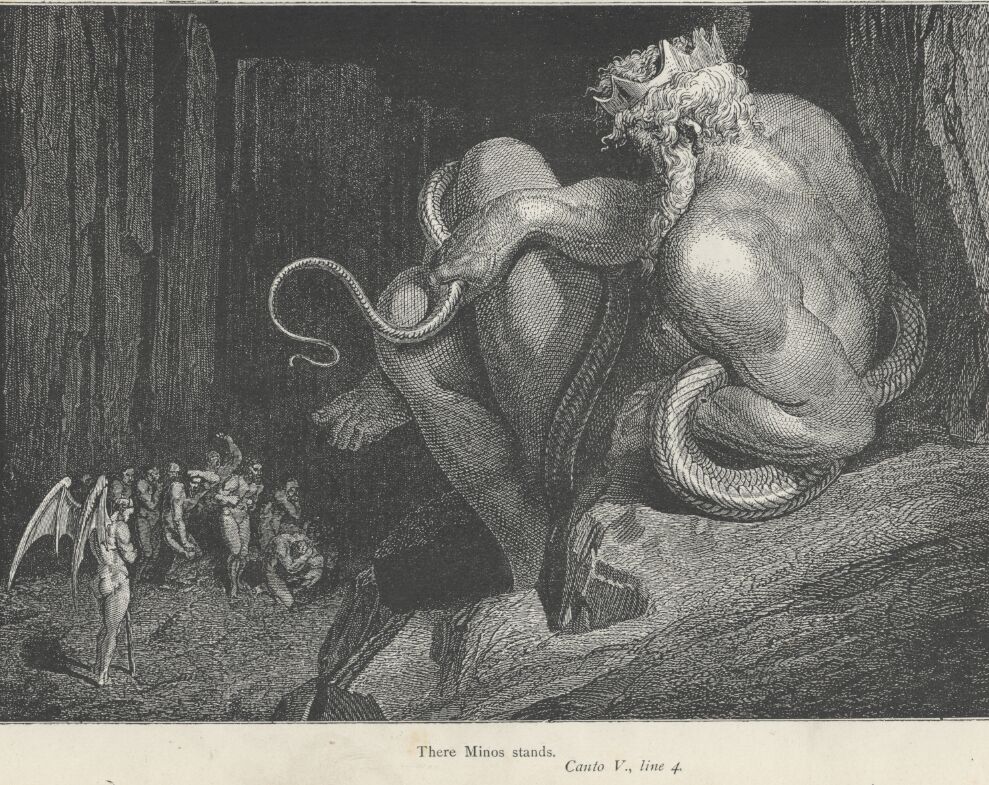

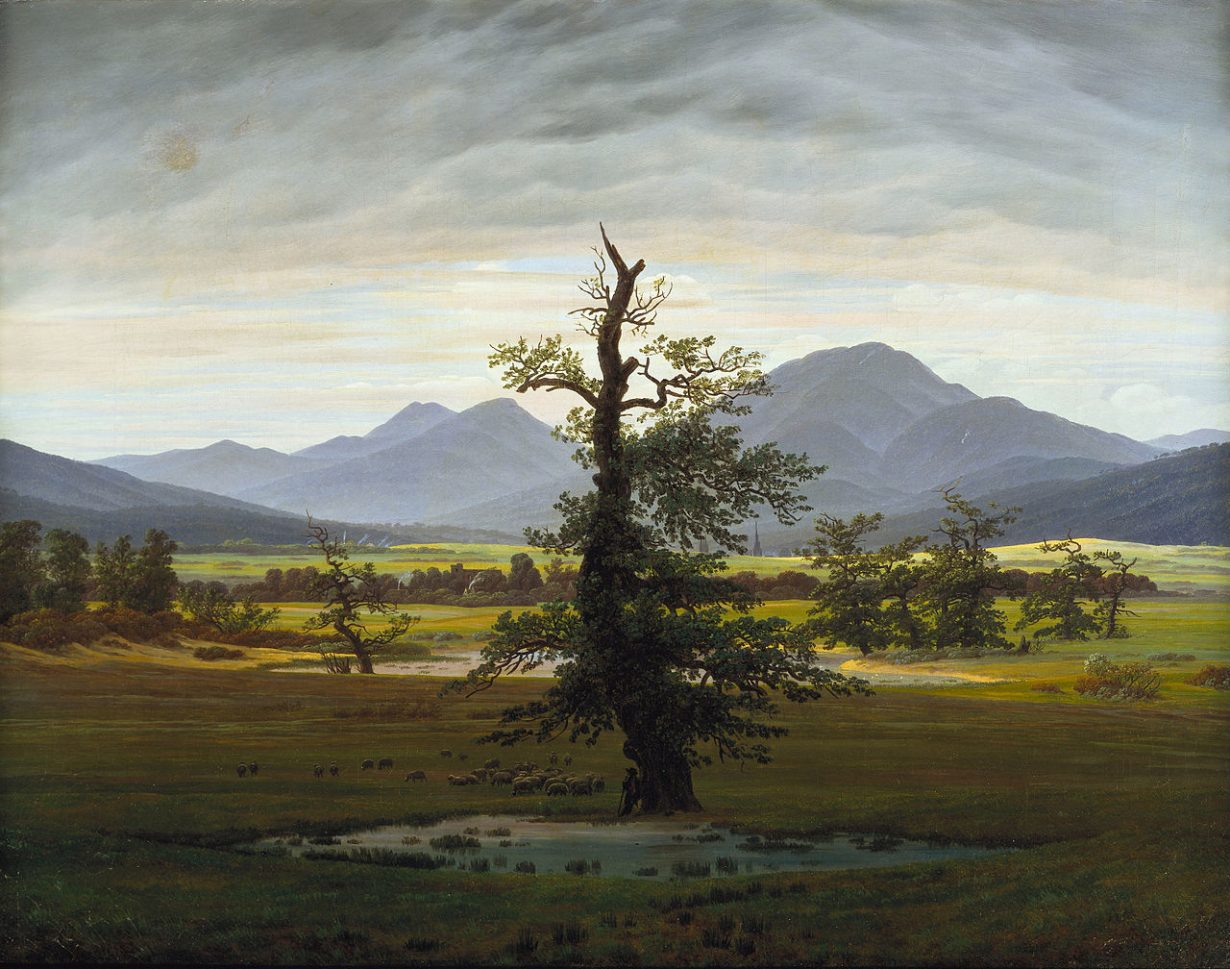

For those familiar with Elden Ring, the association here might already be obvious, but for those yet to visit the game’s ‘lands between’ it is worth unwrapping this connection. Developers FromSoftware have never been shy about their influences – particularly the heavy influence of the late artist Kentaro Miura’s dark fantasy manga Berserk (1989-2021) on their games’ weighty armour, massive swords, and horrifying beasts. But Berserk itself is a melting pot of pulp and classical imagery, welding Gustave Doré’s inferno or Caspar David Friedrich’s trees to the likes of The Evil Dead (1981), with Miura even drawing demons directly from the work of Bosch into his devilish bestiary.

Elden Ring then continues this amalgamation of pulp and religious art, and is filled with Boschian strangeness; whether in its battles with misshapen monsters, interventions into rituals of obscure provenance or oscillation between the horrifying and the ridiculous. The premise, which casts the player as a ‘tarnished’, a pitiful figure aspiring to ascend to sainthood through the murder of corrupt demigods, sets the scene for a diseased landscape of wartorn hovels and besieged castles, where wraith-like knights and twisted monsters pick at the remains of once grand ruins.

In some ways, Elden Ring evokes Brian Catling’s haunting novel Hollow (2021), which builds a grim and surreal fantasy world out of Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s paintings, setting a group of mercenaries on a quest to carry a disturbing bone-eating oracle to the foot of a ruined Tower of Babel, where in the Glandula Misericordia a perpetual war is waged between the living and the dead. Like Catling, Miyazaki and his team see Bosch’s work as a landscape of beauty and terror to be brought to life and explored. And both Miyazaki and Catling take Bosch’s absurd rendition of his fifteenth-century malaise, an era defined by senseless war, disease and corruption, and amplify it. The dead taunt the living, the earth spews out demons and any institution of power is twisted beyond humanity towards something perverse and rotting.

But it is not just about Elden Ring evoking Bosch, because as I sank hour after hour into my journey across its ruined lands, I found myself coming back to those harsh and unusual crops that Boschbot churns out as the key to something the game was also exploring. Unlike FromSoftware’s labyrinthine predecessors, Demon’s Souls (2009), Bloodborne (2015) and the Dark Souls series, Elden Ring presents the players with an open landscape, a vast territory which the player can freely navigate.

As you explore, this world expands impossibly, down to purpling depths or up to crystalline peaks, testing your sense of scale and direction. Whether they resemble a rocky hillside from which the remains of a gothic cathedral has been cast, or an extreme close-up of a fungally-infected corpse, the regions of the game provide visually expansive canvases onto which secrets, caves and ruins can be delicately placed. Challenges can be approached in almost any order, dungeons explored, horrors experienced, secrets unwound at leisure. In this way Elden Ring breaks with tradition: not so much a long, dread-infused dungeon crawl, but a world of fragments which, like images in a prism, align themselves depending on the player’s position.

Like the titular bot of Boschbot, a roving mechanical eye that selects (by some arcane process) imagery from a wide canvas of potential strangeness, so in Elden Ring the player takes on the role of witness to a world which is in turns surreal, comical and starkly atmospheric. They are the ones who assemble the pieces and arrange them into narrative structures of experience. FromSoftware seem to have attuned the game perfectly for this, slicing through it with shortcuts, one-way magical gates, vantage points and vague directions.

The result is a landscape etched with narrative detail, each ruin drawing the player to a strange vignette, with all the trickiness and unreliability of a mischievous narrator. Because of this, to play Elden Ring is to make a whole from fragments, to let your eyes be guided around the painted landscape and in it find humour and despair, violence and absurdity in equal measure. Its quality, beyond the sheer imaginative richness of its bestiary and landscapes, is in the way it rewards wanderings, just as Bosch’s paintings reward a curious eye, with arrangements that might evoke awe or laughter, or perhaps a spluttering combination of the two.