The artists discuss the Pakistani diaspora, miniature painting and the ever-present weight of the Partition of India on their lives and work

Artists Shaan Syed’s and Nurjahan Akhlaq’s time studying at Goldsmiths College overlapped in the mid-2000s, but they didn’t know it back then. They might have been at house parties together, Akhlaq admits. In the south London studios, Toronto-born Syed was exploring making pared-back, spatially self-conscious abstract paintings; and Akhlaq, hailing from Lahore, used collage to understand years of childhood migration from Pakistan to the US and Turkey with her father, the esteemed modernist and educator Zahoor ul Akhlaq.

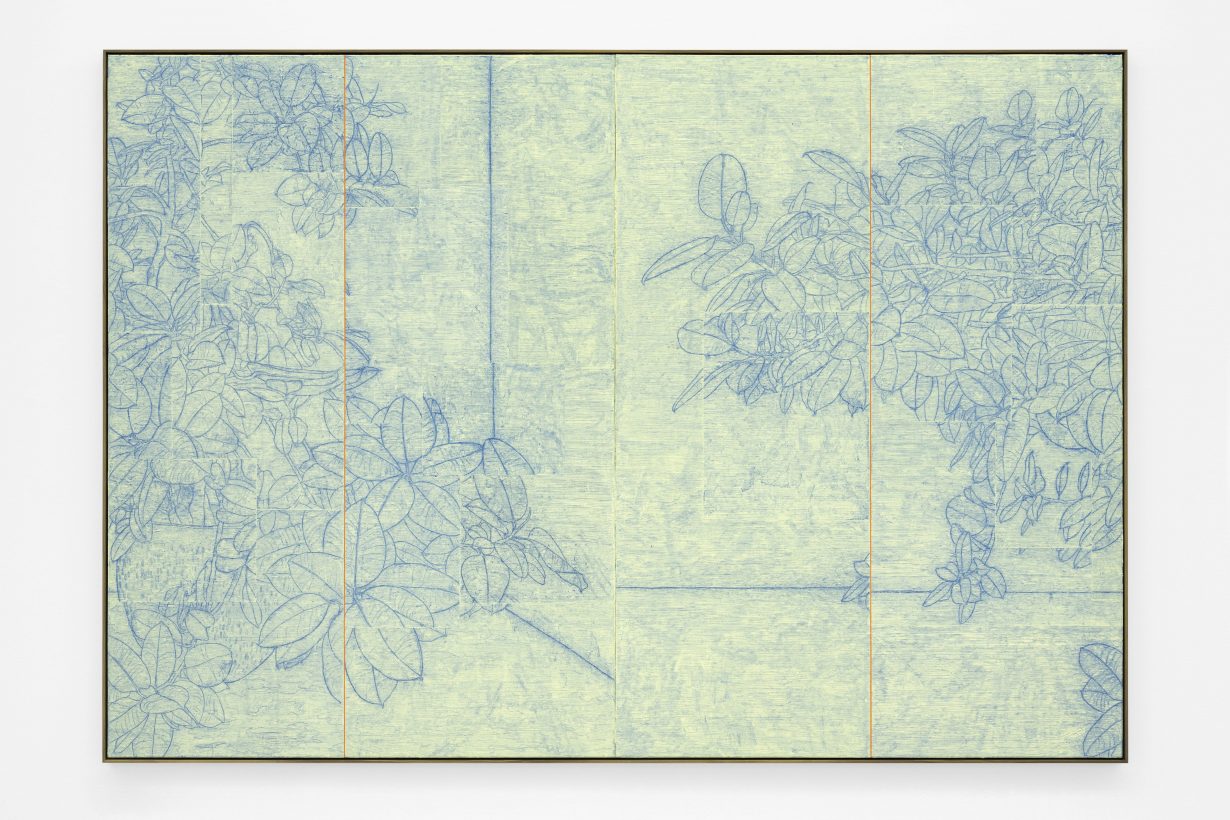

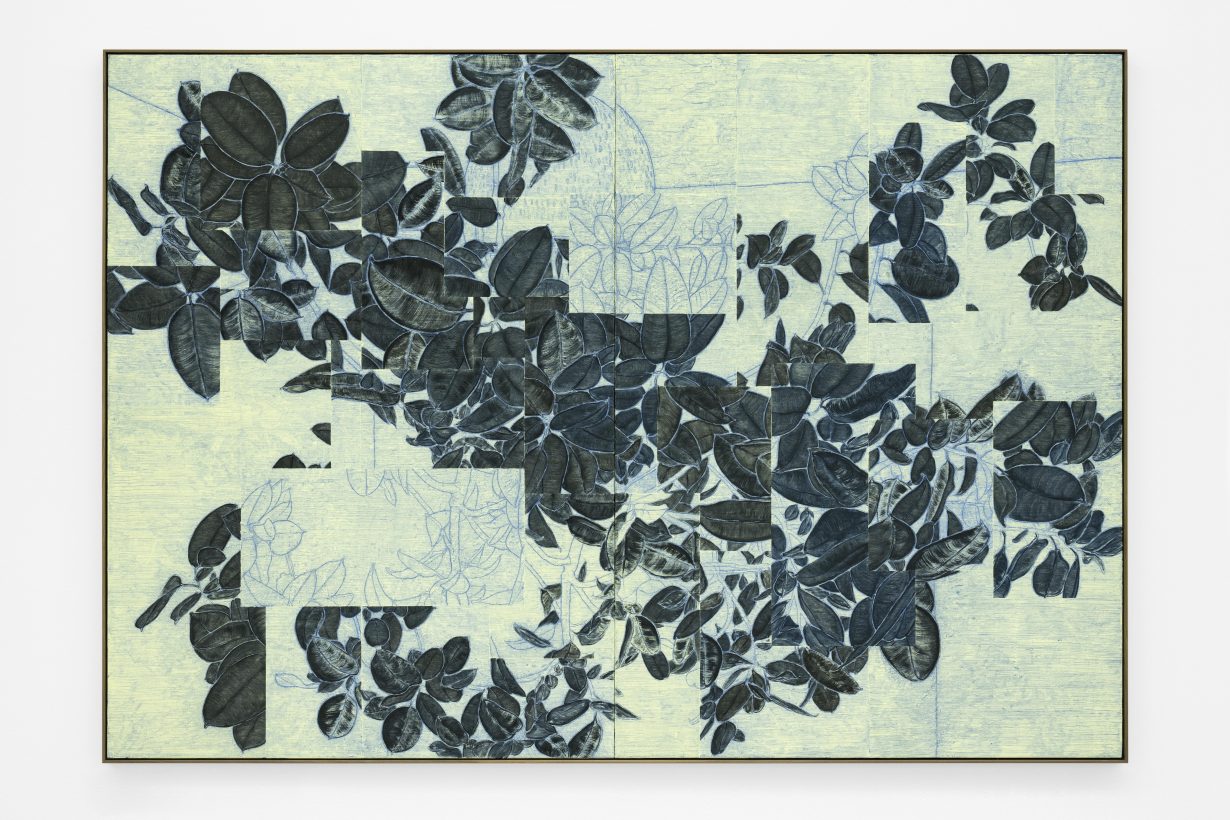

The pair were only properly introduced earlier this year by a mutual friend, prior to the opening of Syed’s current show Les Rapports at Bradley Ertaskiran in Montréal, where Akhlaq now lives. Syed’s paintings have expanded from abstraction to reflect what he calls his family’s migratory ‘trajectory’ – from the British Raj to the UK and then Canada – and also a host of regional motifs and references, from the Iraqi Great Mosque of Samarra which informed the blocky, ziggurat-shaped paintings in his 2020 exhibition Thank you India, Goodbye Pakistan, Hello England, to the rubber tree which is the starting point for the three double-panel and 29 painted works on linen in Les Rapports.

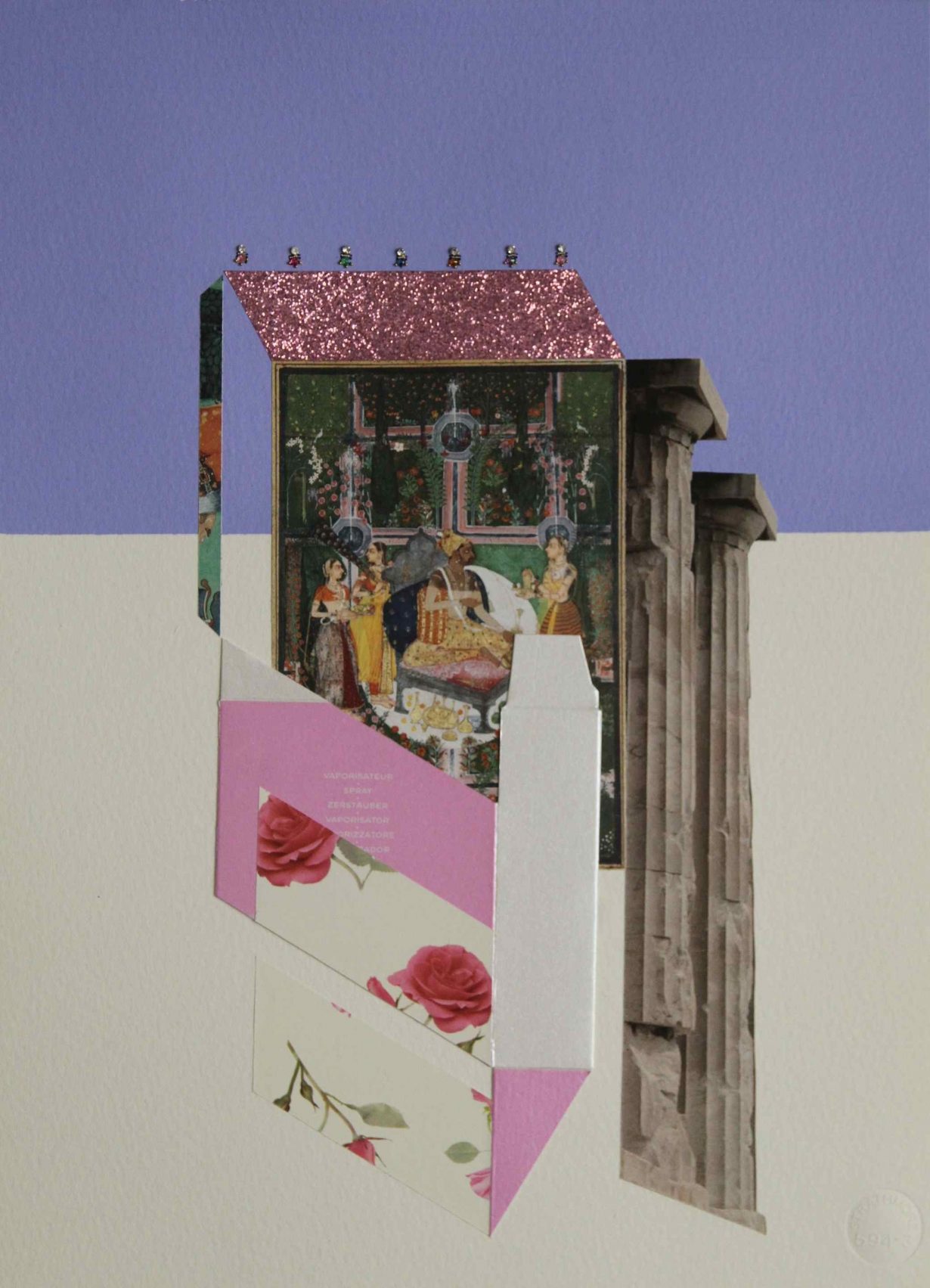

Akhlaq, whose South Asian and abstraction-inspired collages have developed into a filmmaking practice, has spent much of the last decade organising and overseeing her father’s artistic estate after his murder in 1999. Her work has allowed a new generation of artists to encounter the multiple strands of Zahoor’s practice, adding another layer to the current surge in interest in contemporary miniaturists like Shahzia Sikander, Rashid Rana and others, some of whom feature in the landmark show, currently in Plymouth, Beyond the Page: South Asian Miniature Painting and Britain, 1600 to Now alongside Zahoor. Syed’s and Zahoor’s work share much in common, the pair agree, and plans are in place for a joint presentation in London next year. Artistic influence can be unconscious, chronologically fluid, and have liberating aftereffects. Syed’s canvases can, at points, resemble American mid-20th century abstraction, rather than what might be thought of as stereotypically South Asian art, icons which sometimes appear in Akhlaq’s own collages. Such dissolving of the boundaries between East and Western art history owes much to Zahoor’s experimentation with shape and space at Lahore’s National College of Arts over six decades ago but, like others, Syed has only recently discovered his work.

AR Syed, can you start by explaining the ideas and processes behind Les Rapports?

Shaan Syed The exhibition centred on an image of a huge rubber plant, one which happened to be decorating the lobby of Kunstmuseum Basel. Thinking about the rubber plant’s history, it became the anchor; several of the paintings are based on breaking down an image of the plant into sections. The plant image gets disjointed and reconfigured, and I use a technique of drawing through paper – which then means I have all this paper which bears the evidence of this drawing into the wet paint of the works. The paper bore the imprint of a process to make the double-panelled paintings, so I started cutting them up and pasting them onto new paintings, which is what forms the remaining works on a salon-hang wall. They look like screen prints, so there’s this tension between the two different mark-makings which gives the show its title. I’d also been thinking a lot about Partition in the run-up: Could this salon-style wall be a monument to Partition – of stories untold, retold or hidden? That’s the framework for thinking about the rubber plant as an emblem.

Nurjahan Akhlaq There were two things in your work which remind me of my father’s. One was the use of the bright neon cross-marks on the salon paintings. The second was the breaking of the three-point perspective on the diptychs, where your eye has to work harder to follow the flow of the lines. The flatness of space is something that my father identified in miniature painting, or traditional ‘Eastern’ painting.

SS This is where the connection between us started: you sent me an image of a Zahoor painting which had the same cross motif on it. Space in Eastern and Western art history have such different trajectories. It seems to me that your father was really attuned to the tension in how those trajectories are mapped while also having a foot in each school of thought.

NA When my father attended the National College of Arts, Lahore, in the late 1950s, his work looked like traditional Western abstraction, informed by Cubism. Over 400 years of British colonisation, miniature painting had dwindled into twee craft forms – it wasn’t seen as contemporary art. Zahoor’s contribution was to take things from the language of miniatures and use them in conversation with his canvases, which were larger and more experimental, working in oil and then acrylic, sculpture and printmaking. He balanced Western post-Renaissance influences and his own tradition.

Zahoor went to London in 1966 on a British Council scholarship to study printmaking. (The expectation at that time for lecturers was that you would go abroad, learn a new skill and then return and be able to teach it). He found his way to the V&A and befriended Robert Skelton, who was the curator of Indian department, and so had access to unique miniatures which were not on display, studying the painterly language rather than the decorative aspects. He also used traditional Islamic calligraphy; I don’t think he was a very religious person, but calligraphy is a sacred art in Islam.

AR What is the relationship between how objects and histories migrate across both time and space in your work? And how did your respective educations in visual culture influence your thinking?

SS The rubber plant has become such a cliché in home interiors, and I took it for granted before I found out that its genome lies in South Asia. That got me thinking about how I was implicated in this symbol which hides in plain sight; it’s a motif which holds the trajectory of East to West.

I’m interested in objects which are taken from one place to another, especially with tourism. A similar thing happened when I visited Morocco and started learning about Berber rug weaving. I came back with one and noticed them everywhere: on Instagram feeds and even in John Lewis. I was implicated in that cliché too. These contemporary objects come loaded with histories that are now being reconfigured.

NA For me, collage is the perfect medium to bring together different imagery and sources. I lived in Lahore until the age of eight, then moved to New Haven, then back to Pakistan, then Ankara, then we settled in Canada. My parents collected folk art, but I started making collages at Goldsmiths. I moved to Lahore in 2014 and started frequenting the Anarkali market, where I would buy used art books to up-cycle for my collage works.

SS Collage is a medium that allows sources from different pots. It has a wonderful immediacy, especially when you’re dealing with weighted ideas like culture and history. The action of glueing one thing to another has a celebratory irreverence.

AR What do you think is the responsibility of a cultural custodian? And how do you negotiate these legacies within Western art histories and institutions?

SS My mother was English; my father Muslim Pakistani. He was 14 when Partition happened. Growing up in Canada, there was always this tension in the household between two ways of being in the world. The South Asian objects and images around the house became talismans for difference. Since my parents died, I’ve been thinking about these issues in a more pointed way. My life is the result of a very long trajectory. It starts with my father being born in India, living through Partition, fleeing to Karachi, then moving to London – the heart of the British Empire – meeting an English woman, and them deciding to leave for the ‘new world’ with a hope and naivety that they might escape the racism that the relationship was experiencing. But it was also a move away from the heavy and long histories of their native countries. Then there’s me, coming back to the Empire in its last gasps. I don’t have kids, so I am the endpoint of this trajectory. I have to ask myself: who is (or am I) the custodian of that trajectory? It’s a trajectory which is frustratingly ignored in the UK; kids don’t learn what partition is in school, which is astounding to me.

NA My mother was born in Lahore in 1948, so Partition has always been a present dialogue, but only recently within diaspora and Canadian circles. In terms of custodianship, on a material level, Zahoor’s archive has just been digitised by the Asia Art Archive. The importance of material came through when I was living in Lahore in 2016. I found lots of 35mm slides, negatives and prints beyond just artwork documentation, looking at indigenous architecture, culture and folk art across Asia. I had the idea to make a film portrait of the artist through the archive given the amount of lens-based media. It’s a dialogue I’m having with my Dad; I was 19-years-old when he died, there were so many conversations we didn’t have. I hope I can do justice to the responsibility I have to his work; sometimes I do ask myself whether I’m making the correct choices.

AR Have you noticed changes in the way that South Asian artists are viewed in recent years?

NA There’s more interest in the Global South in the art world now. Regionally too: attending the Dhaka Art Summit a few years ago, people there remarked on the high level of Pakistani art. Sometimes I think that we are still entrenched in the binary world of East and West in political discourse, but we’re in a time where the canon is expanding, and people are definitely becoming more aware of its Western-centric focus. Time will tell where it goes, because these can also be fads. The discourse is changing, and things are definitely more interesting than 20 years ago. I always find the ‘artists-of-colour’ label a very strange label which I can’t come to terms with, but I feel that those things are shifting.

SS When I lived in Toronto in the mid-1990s, there were certain diaspora organisations like Desh Pardesh which I was part of, but it always sat uncomfortably with me. I had this question: Do I want to be an artist of colour? Or will that mean that my work is funnelled through that lens all of the time. But I agree that now these conversations are opening up, and we don’t have to be part of these groups to get our work seen anymore. There’s a bit more interlacing starting to happen.

Shaan Syed’s Les Rapports is on at Bradley Ertaskiran, Montreal, through 9 March

Beyond the Page: South Asian Miniature Painting and Britain, 1600 to Now is on at The Box, Plymouth, through 2 June