The artist’s project centres the ways in which historical narratives evolve as time progresses

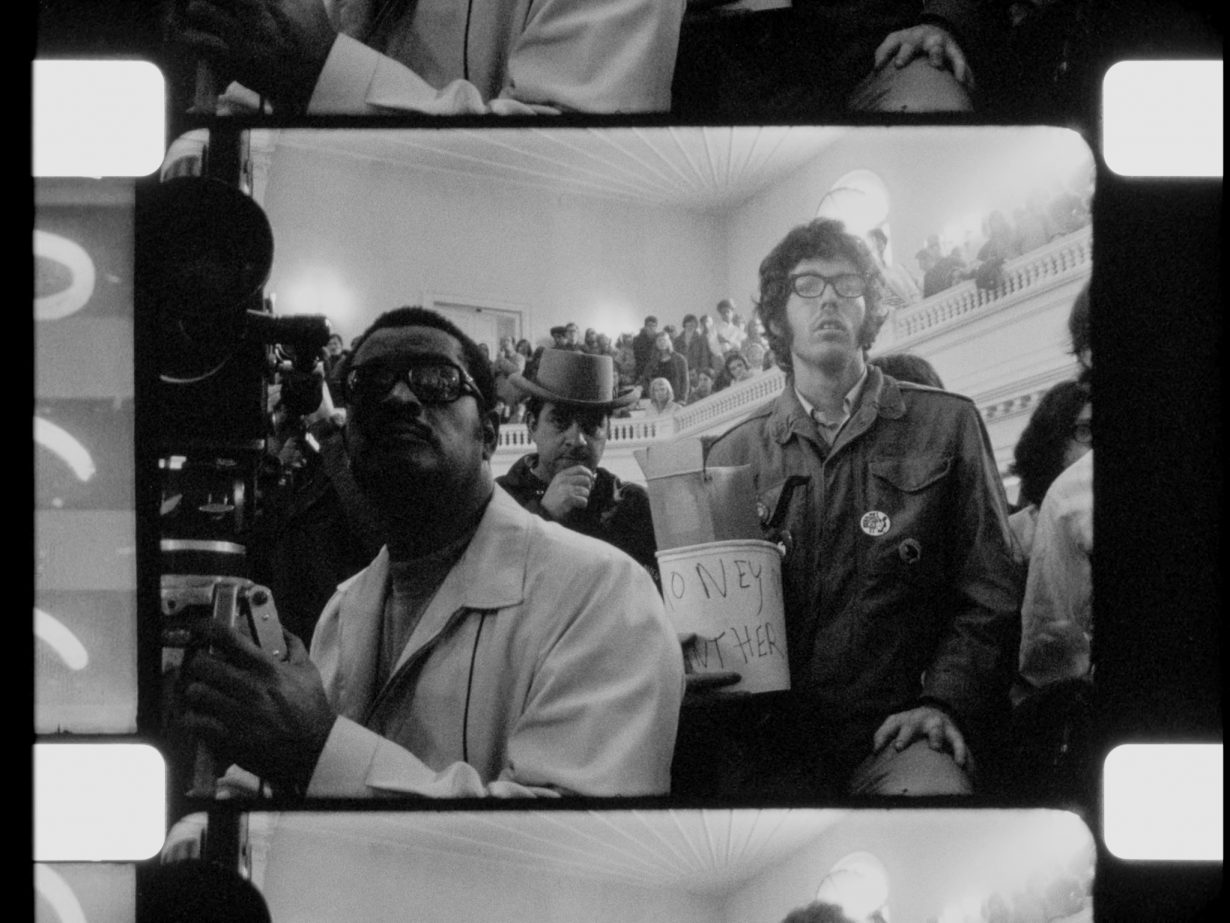

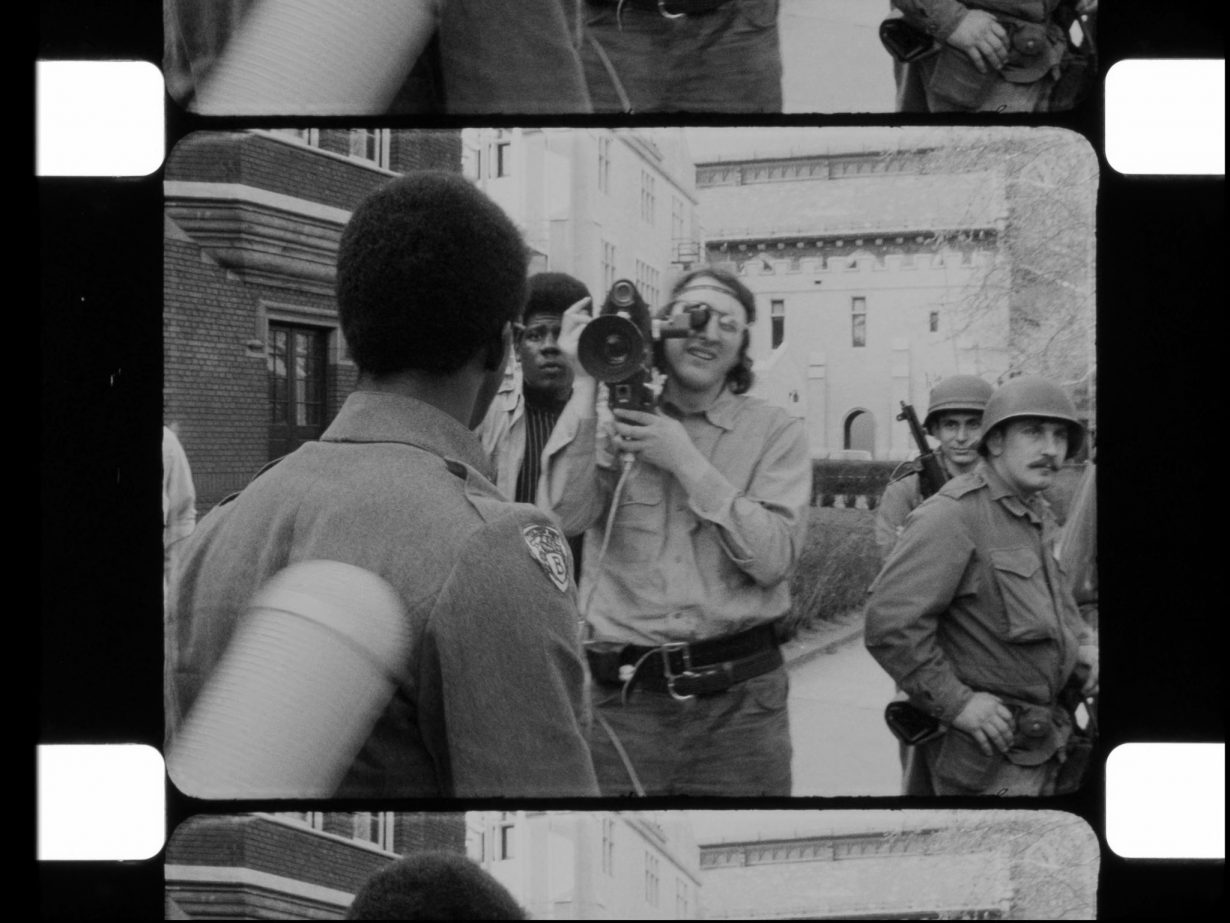

The two tragic events that propel Naeem Mohaiemen’s new 90-minute, three-channel videowork, THROUGH A MIRROR, DARKLY, appear one on each of its side projections: on the left, captured in grainy still photography, lie the slain bodies of the four students killed by the Ohio National Guard during a 1970 anti-war protest on Kent State University campus. On the right, are the bodies of the two students shot dead by police at Jackson State College 11 days later, although they are largely obscured as peers crowd around attempting to revive the victims. The middle screen shows footage filmed by Mohaiemen of the end of a memorial film screening – in what looks like a university lecture theatre – attended by the now much older survivors of the Kent State incident, just as Bob Dylan’s Forever Young (1974) plays over the credits and the funders of whatever film the audience were watching are thanked. The crowd shuffles out.

THROUGH A MIRROR, DARKLY (the title a New Testament quotation from Corinthians 13, suggestive of oblique understanding), follows a formal pattern evident in the US-based Bangladeshi artist’s previous work, in which archival documentation is mixed with new interviews and location visits. The evident hierarchy of the visuals is an indication that the artist’s project is not about dissecting past events per se; rather it’s about centring the way in which narratives surrounding those events have evolved as time progresses. “I’m not trying to reconstruct the Vietnam War or the protest against it, because there is a mountain of work around that – even with its blind spots,” Mohaiemen tells me during a video call from his home in New York. “I’m looking at the act of remembering and the memorialisation process.”

In the aftermath of the killings, the universities would disavow memorial events such as the one at Kent State, the artist says. “Students were on their own. Then gradually, the university thought this is something that fits with how they want to present themselves.” In part this was a consequence of the anti-Vietnam movement: those once branded as committing ‘campus terrorism’ in one archive clip, now winning sympathy, albeit retrospectively as the US lost the war in Asia. “So those memorials became my interest: those who write about it, those who go back to these ceremonies year after year, those who were not there in 1970, but still use terms like ‘our’ and ‘us’.”

Accordingly, as THROUGH A MIRROR, DARKLY progresses it approaches the state-sanctioned killings (the shooters at Kent State were acquitted of all criminal charges; no one at Jackson was ever charged) from changing points of view.Clips of President Nixon and other politicians are woven together with those repulsed by the government violence. In the juxtaposition of clips and interviews Mohaiemen parallels the cruelty and loss of life inflicted on the Vietnamese in the war with that perpetuated at home against protesters and students. When a mob of construction workers and office workers rioted against student protesters gathered on Wall Street after the Kent and Jackson killings, we learn that Nixon invited some of their number to the White House. It comes together as a portrait of a sick nation, but also leaves viewers pondering the question of whether or not the country ever recovered from this trauma: it is noticeable how much bigger the commemorations for Kent State are, when compared to a vigil for Jackson State, which attracts a smaller (though passionate) audience, sitting on foldable chairs on an otherwise desolate outdoor plaza. The students slain at Jackson State, James Green and Phillip Gibbs, were Black and the college (now a university) was a historically Black institution. Mohaiemen says their race was, and remains, a major factor in the relative amnesia surrounding the event: the pair’s murder occurring during a protest that sought to address prejudice at home as much as it did US foreign policy. “From the moment Kent State happened it immediately catapulted into international consciousness. There are things that people could read into it. And there are ways that people could look at those four children and say ‘our children’.” White, middle-class children. “Jackson State didn’t feel like ‘our’ children to the media. It did, of course, to African Americans, but that was not the dominant voice driving the media narrative.” However, Mohaiemen adds, the protests were never catalysed by one set narrative – this is why the memorialisation of the killings became so subjective. Race, foreign policy and class consciousness “are not binaries”.

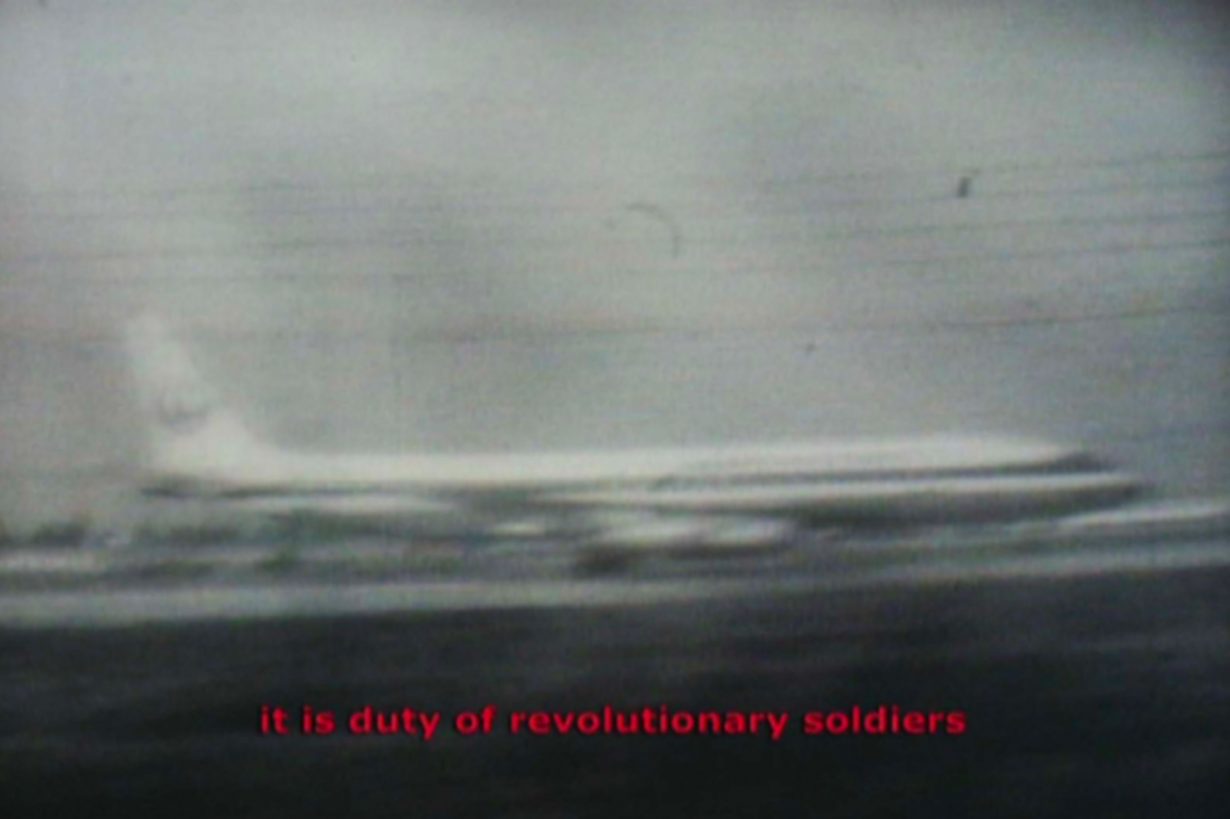

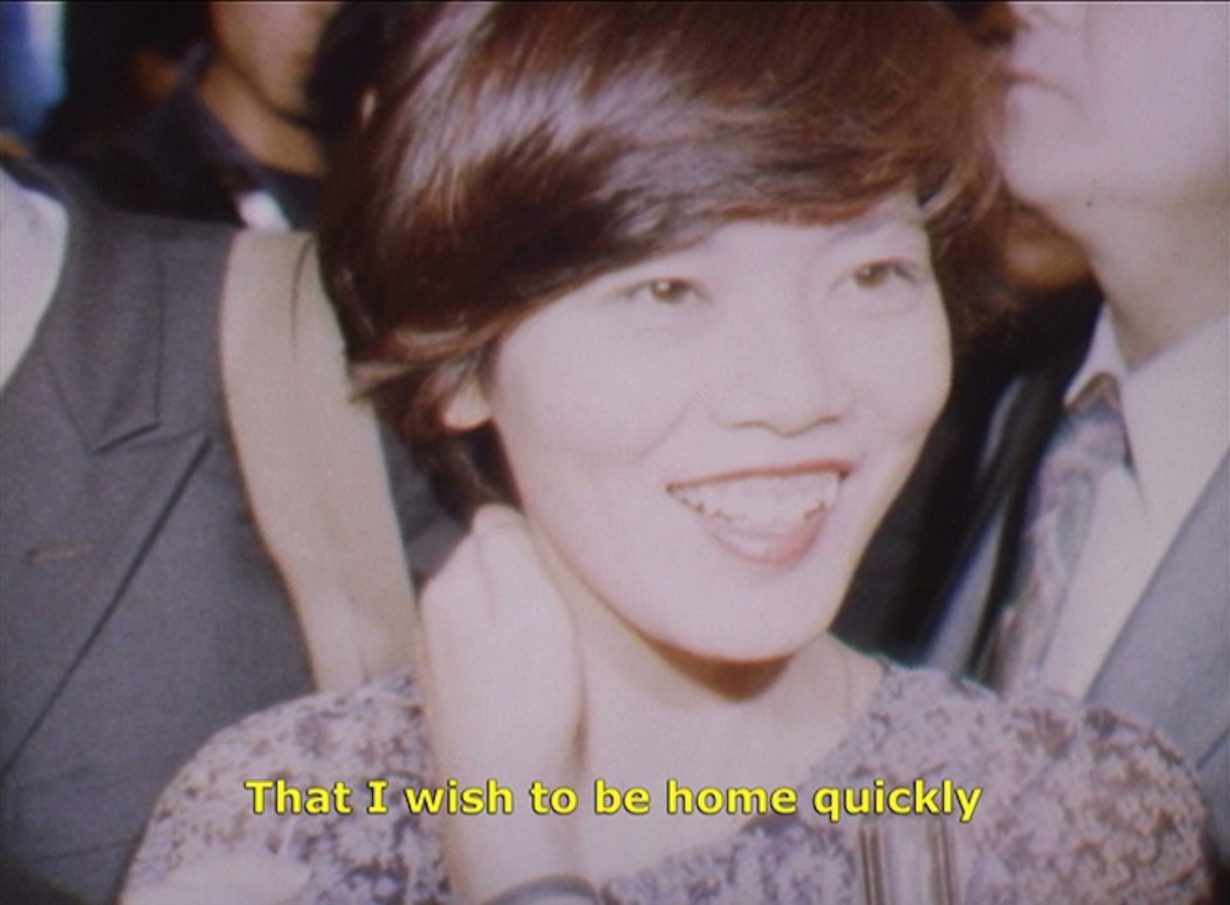

Perhaps it is seeing the aging faces of the one-time student activists, perhaps it is the awareness that another blow-hard occupies the White House, that US foreign policy is once again catalysing campus unrest (not least the pro-Palestine encampments at Columbia University, where Mohaiemen teaches) – but the film seems seeped in what Walter Benjamin described as ‘left-wing melancholy’. It is a feeling, consciously parlayed and played with, that is characteristic of Mohaiemen’s earlier works and their address to historical, transnational left-wing alliances: United Red Army (2011) which centred on the hijacking of a plane by the radical leftist Japanese Red Army in 1970; Two Meetings and a Funeral (2017), made for Documenta 14, in which Mohaiemen surveyed the tensions between the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) during that same decade; Tripoli Cancelled (2017), made for the same Documenta and a foray into fiction, a portrait of a man seemingly left stranded in a crumbling and otherwise deserted airport. They all have the feel of eulogies to missed opportunities and the moments left wing political projects might have been achieved but ultimately failed.

Documenta 14, Athens, 2017). Photo: Michael Nast. Courtesy the artist and Documenta 14

“A theme in all my works is how a moment that you think might galvanise a progressive turn unexpectedly opens the door to something completely different. At the time these killings were described as a transformative moment. It was presumed they would empower an anti-war candidate in the 1972 election. In some ways it did. George McGovern was the most anti-war candidate to ever run for president, but he lost. This spectre of innocence – the student, protesting and getting killed – was used instead to mobilise the reelection of Nixon, who could come out and say things are out of control, and that he was the man to fix it.” The criticism that might be levelled at the act of memorialisation is that melancholy, in Benjamin’s conception, contains within it a morbid attachment to failure, one that blocks any recovery from loss. At heart, leftist utopianism is a speculative process – so much of Mohaiemen’s work has a correspondingly hypnotic quality, in which shots are taken from unobtrusive angles, pauses in interviews remain in the edit and the archive footage feels degraded and aged by the fog of time. But the artist is a realist: “It isn’t enough to have only moments, you need them backed by transformative political change,” he agrees. The plaques and obelisks that the artist surveys in his new film seem too frozen and solid to offer anything that might catalyse productive movements; rather they seem more a teleological self-deception.

Mohaiemen was born in Britain to parents who were from what was then East Pakistan; the family moved back when he was still a baby, just in time for independence and the foundation of Bangladesh. Naeem’s childhood was spent in Dhaka as well as Libya, where his father, an army surgeon, was stationed. He has now lived over half his life in the US, arriving as a student in 1989, but this is the first time he has addressed his adopted home in his work. “Going to college in Ohio I had been interested in the events of Kent State for years, but only maybe in the last seven or eight years did I become aware of Jackson State. As I started to tell people about this project I encountered a bit of confusion based on the fact that the work wasn’t about Bangladesh or even about South Asia. There is a hegemonic mechanism that does encourage you to make representational work about where you’re from.”

I ask whether THROUGH A MIRROR, DARKLY is explicitly a commentary on the current state of the US. I tell the artist how, from afar at least, there seems very little coherent opposition to Donald Trump’s administration. The artist replies that he started the work before the “current crises”. “The present kept transforming as I was working on the project, and for me the main task at that point was to not get into a CNN-response hamster-wheel of responding and changing the film as I went. I wasn’t trying to explain the now with the then.” Instead, it becomes a study of activism and personality, the main characters split between those for whom the memory of the tragedies galvanised a life of social and political engagement, and those for whom it remains an event marooned in the past, revisited and mourned once a year but no more. Mohaiemen is insistent that he is not seeking to judge either reaction, but it is clear where his sympathies lie. He cites the example of Mark Lencl, one of the figures who appears prominently in the work, as a figure whose life has been fundamentally altered by the events of Kent State. Lencl went on to join the militant Weather Underground, and now works with organisations such as the POOR News Network, an Oakland-based working-class-focused community media platform.

When Mohaiemen first moved to the US he was a central figure in Visible, a collective of artists, activists and lawyers investigating the post-9/11 security panic, racial profiling and the effect on immigrant communities. He went on to be involved in Occupy Wall Street. So, does he see his artwork as an extension of his activism? “There is a part of me who is involved in various activist struggles,” he replies. “I support, currently, Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral campaign, for example. I’m still doing, in my microscopic ways, what I can. There’s that part, but then, when I’m making my projects, I try to separate them out. Because I’m not trying to make films that are useful for left-wing struggle. Sometimes that brings me into conflict with comrades.” I suggest that any historiographic project is intrinsically entangled with the idea that it might offer lessons for the present. What might that be for Mohaiemen? He doesn’t answer directly. But events, even dramatic ones, in themselves don’t bring change, they have to be part of a greater narrative: otherwise they just slip into becoming mere memories. “You need to build on them,” Mohaiemen says. “But how do you build movements?” When I think about the artist’s new work I can’t help thinking that while it proffers a warning about inaction, perhaps it also offers, in figures such as Lencl, and despite Mohaiemen’s protestation, a blueprint for the future too.

Naeem Mohaiemen’s new film THROUGH A MIRROR, DARKLY is presented by Artangel at Albany House, London, 21 September – 9 November

From the September 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.