Why it would be better if the filmmaker aspired to be less of a historian, and more of a philosopher

I love Adam Curtis films. Yes, I know there’s an argument that they’re all style over substance, the credulous person’s idea of a master of suspicion. Yes, I know that his technique and his rhetoric and the scope of his interests are so well-defined, so immediately recognisable, that he often seems to be veering towards self-parody. But I can’t help myself: I grew up watching Adam Curtis films. When I watch them, I feel at home. They might not be as profound as I thought they were when I was a teenager – but that doesn’t mean they aren’t wonderfully, bombastically fun. Adam Curtis, the poet of the Wikipedia binge: skimming over the surface of the superstructure, sparking sudden, otherwise hidden connections into perfect, blinding clarity. Sculpting the detritus of every news cycle he’s ever been subjected to, the whole of his adult life, into a sprawling rhizomatic narrative, endlessly exploding everywhere, of how and why It’s All Gone Wrong.

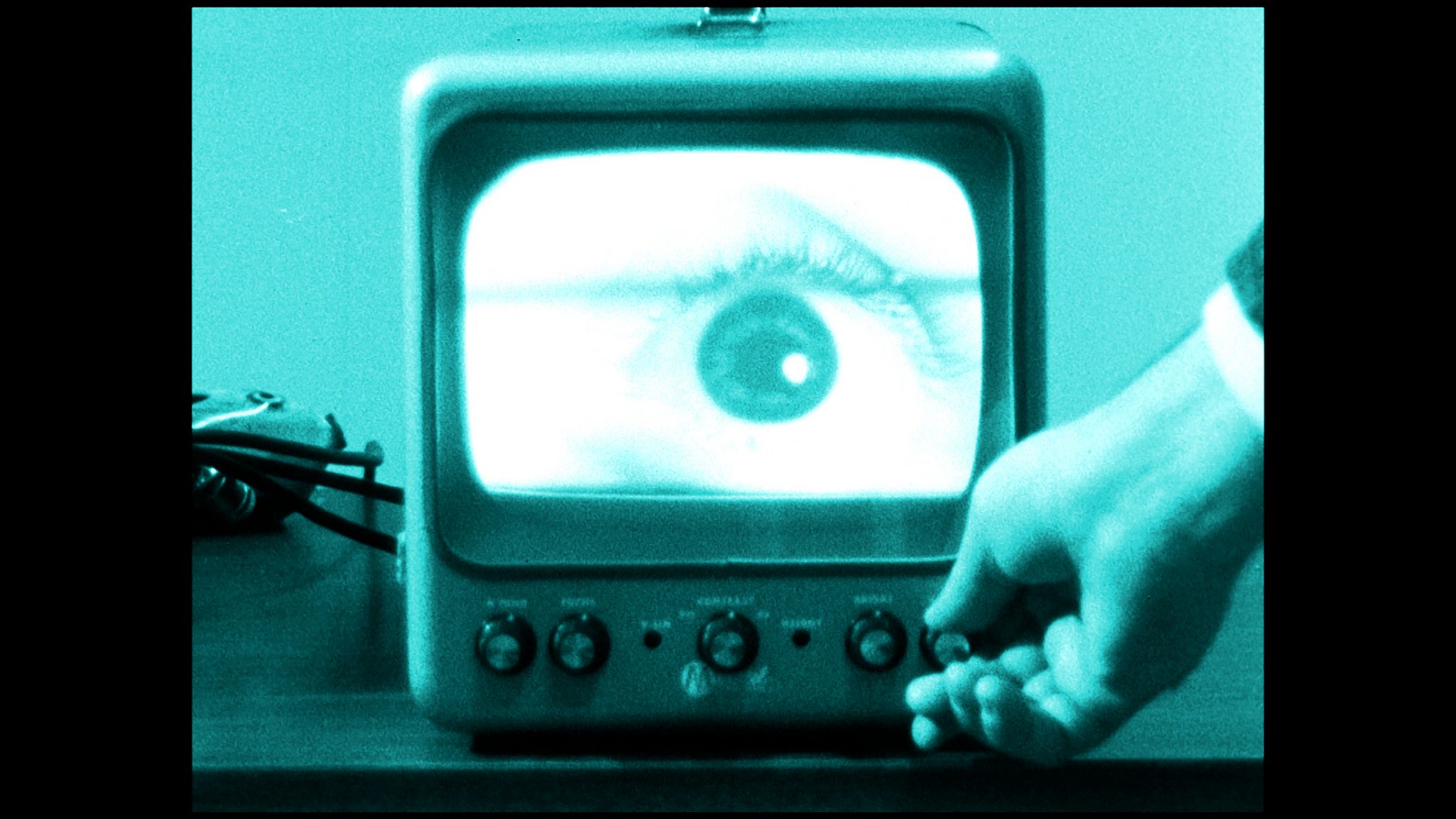

If, like me, you really enjoy watching Adam Curtis films, then starting this week you’re in for a treat. Can’t Get You Out Of My Head (2021) consists of six films, all around 75 minutes long: his first true series since 2011’s All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace, and his longest since Pandora’s Box, way back in 1993. Judging by the rough cuts I’ve seen, if you’ve ever seen an Adam Curtis film before, you will not be surprised by what any of the episodes are like: Can’t Get You Out Of My Head both looks and sounds like everything else he’s ever done, and is built around roughly the same themes. Billed as ‘An Emotional History of the Modern World’, the series is primarily focused on the conflict between individual and collective authority, the rise of anti-democratic technocracy, and our felt inability to act transformatively in the world.

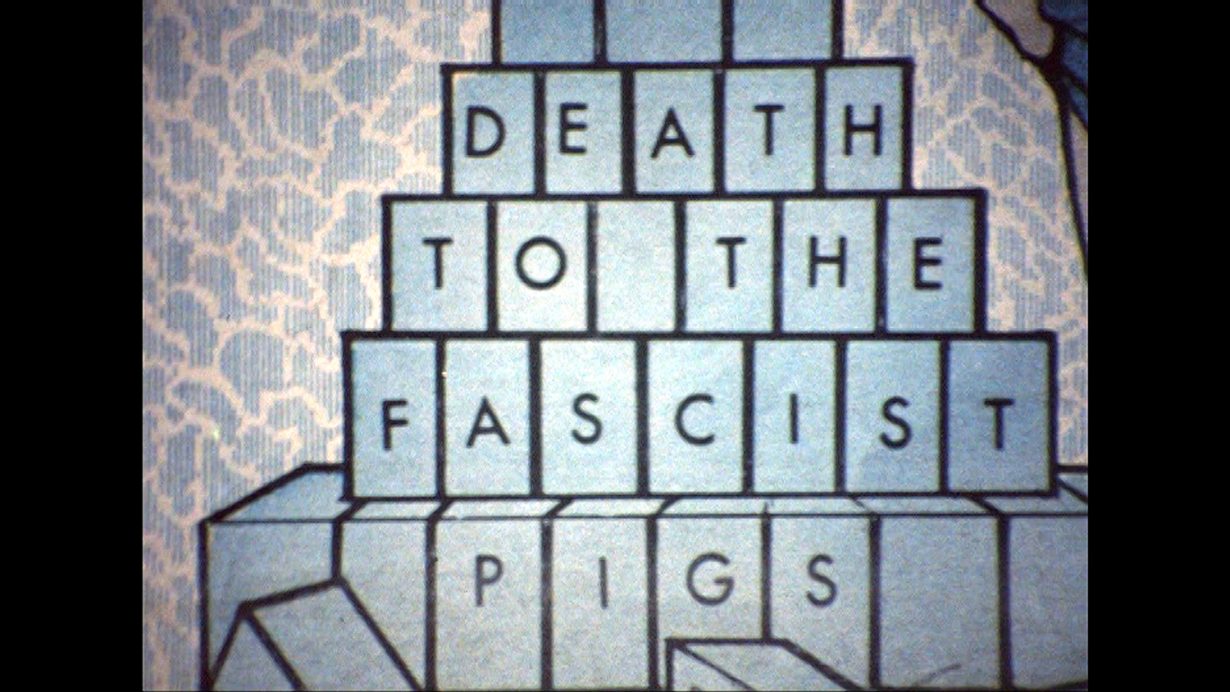

Where the series does distinguish itself, however, is in terms of its ambition and scope. The narrative that Curtis presents spans the whole of the globe – although it is especially focused on America, the UK, China, and Russia. Its structure often feels like that of an epic postmodern novel: to tell his story, Curtis picks out certain strange, conflicted (anti-)heroes – individuals whose successes, failures, contradictions and ambiguities mirror the more general, global forces they exist within. Among the most prominent of these, whose stories run over several episodes, are Michael de Freitas, aka Michael X – slum landlord, gangster, radical black rights activist, and murderer; Jiang Qing – wife of Chairman Mao, architect of the Cultural Revolution, and fiercely ambitious radical individualist; and Eduard Limonov – trendy Soviet émigré novelist, punkish enemy of global financial capitalism, and fascist. Along the way, Curtis introduces us to a whole host of other histories and individuals – taking in everything from the rise of conspiratorialism, the collapse of the coal mining industry, the life story of Tupac Shakur’s mother Afeni, the West German student movement, the Voynich Manuscript, and trans rights.

In each case, the lives Curtis portrays are used to illustrate the tension between individual autonomy and collective authority – a tension which often manifests itself directly in the actions and motivations of these particular individuals. In Curtis’s telling, as ever, attempts to strengthen the individual against a sick society, while often motivated by noble ideals, are ultimately self-defeating – because they end up weakening the collective to such an extent that we are left unable to resist the rampant, globalising forces which now reign supreme and dominant over seemingly everything in the world. Curtis’s heroes struggle, as we all do, like an animal against its trap, bleeding to death in its increasingly frantic efforts to tear itself loose.

This is all very interesting – but, for all I am a helpless Curtis stan, from the films I’ve seen, the series is not without its problems. These problems stem largely from the fact that Curtis is, by his own admission, ‘fundamentally a historian’ – and that he is also, we must add, fundamentally a historian who isn’t really interested in economics. Curtis is brilliant when it comes to detailing developments in the superstructure – our culture, our institutions, our ideas and systems of power. But he is much less able to link these developments to the material base on which they are built. If Curtis is anything, he is a reverse Marxist, for whom the superstructure ultimately determines the base. This, I think, is where the accusations of aestheticism which sometimes dog Curtis are most justifiable.

In Can’t Get You Out Of My Head, history can end up seeming just like a bunch of stuff which happened – because one important man decided this, and then someone else on the other side of the world came up with something else, but then those turned out to be just fantasies, and then Bill Clinton got elected, and so on and so forth. There is rarely any particular notice taken of the fact that sometimes things happen because people need to pay rent, or to eat. We drift forever, in a world that has conspired to make us alone and stupid and lost, and if we ever try and do anything good then we are so stupid and lost that it must inevitably go wrong, and end up making everything even worse (arguably Curtis is himself guilty of a form of the ‘Oh Dearism’ he has critiqued as being endemic in television news).

It would be better if Curtis aspired to be less of a historian, and more of a philosopher. Because what he has his finger on in Can’t Get You Out Of My Head is not just a historical problem, but a philosophical one: the question of how the individual is related to society; of why we feel the need to distinguish ourselves in some way from the rest of the individuals who comprise our world, and whether that might ever be possible within a functioning collective. Are we necessarily alone and weak; would we be lost in any crowd? Might we ever strive for anything more, anything grander and more beautiful, than the fatalistic isolation of neoliberal technocracy, or the parochial violence of fascistic nationalism?

Curtis’s series is full of people who have failed in their endeavours because they have misconceived the relationship between the individual and society in some perfectly commonsensical, but philosophically quite basic ways. Clearly, one key lesson from these films is that we need to start thinking about the distinction between individual and society quite differently – in the interests of liberating us from the hostile forces which, as Curtis shows, by now reign almost completely victorious over us all (I have my own ideas about how this can be achieved through philosophy – but unfortunately, I don’t have space to detail them here. Read the early Marx though, and G.E.M. Anscombe, and Iris Murdoch). History can be exemplary in this endeavour – but only through philosophy can we obtain the sort of critical distance from reality necessary to think about our world in a transformative way.

Adam Curtis, Can’t Get You Out Of My Head: An Emotional History of the Modern World, 2021, premieres on BBC iPlayer on 11 February.