The curator explores the legacy of quilting in Black art history as a sociopolitical practice, and its potential for reimagining artmaking today

The New Bend, curated by Legacy Russell and currently on view at Hauser and Wirth, New York, looks at the raced, classed and gendered traditions of quilting and textile through the work of 12 contemporary artists. Its title is an explicit reference and homage to the quilters of Gee’s Bend, a Black women’s cooperative set up on a former slave-owning plantation in Alabama and which, since the 1960s, have become known for their intergenerational quilting practices and their striking, modernist compositions. Borne out of a necessity to recycle scraps of fabric, the quilts have in recent years garnered institutional attention, including a major retrospective at New York’s Whitney Museum in 2002, The Quilts of Gee’s Bend. The show’s artists – Anthony Akinbola, Eddie R. Aparicio, Dawn Williams Boyd, Diedrick Brackens, Tuesday Smillie, Tomashi Jackson, Genesis Jerez, Basil Kincaid, Eric N. Mack, Sojourner Truth Parsons, Qualeasha Wood and Zadie Xa – respond to this artistic lineage in their work, reiterating the need to remake art historical canons.

Russell is an artist, writer and the executive director at The Kitchen, New York. Her recent book – and artworld-sensation – Glitch Feminism (2020) looked at the emancipatory potential of the digital space through the work of artists seeking to rewire systems of race, gender and sexuality and the way identities are performed – Juliana Huxtable, Sondra Perry and Sin Wai Kin among them. Here, Russell explains how a similar multifaceted approach informs The New Bend, tracing the legacy of this part of Black art history and interrogating the entanglement of the medium with class and gender and subsequent distinctions between craft and art.

Clarity Haynes Can you describe your first engagement with the Gee’s Bend quilts and how it informed yoursubsequent relationship with the work and your thinking?

Legacy Russell I don’t remember the exact moment that I first saw a Gee’s Bend quilt. I remember that we had some books, and a poster in the apartment that I grew up in. This was part of the visual vernacular of my being raised in a Black family and growing up in the East Village. It was probably not until I was in graduate school that I came into a greater awareness about how it could exist across visual culture. I think it’s really important to talk about this, because I learned about Gee’s Bend quilts inside of my family and domestic space, but it was not taught inside of the classroom space. Black thought, feminist thought and queer thought often comes in through the lessons that we learn from our chosen families. I think that’s really part of the task and challenge to tackle here – the questions about what is and is not standing inside different models of scholarship and academy and how things are canonised and then brought into the world as part of a broader discourse.

CH When you were studying art history, were you thinking, ‘I can’t believe that this is not part of what we’re learning about?’ I know that you love abstraction.

LR Yes, and the histories of abstraction and modernism that are taught in art history 101 are often dominated by a certain type of white cis-male benchmark. Then within the conceptual framework of abstraction, and incredible scholars like Édouard Glissant, abstraction and opacity come into intersection with each other. Those are really important discussions that I’ve felt deeply committed to as a curator, researcher and student of art history. Queer abstraction and Black abstraction have done important work to crack open and draw attention to some of the failures of pedagogy as tied to abstraction and modernism.

It’s not an uncommon experience for students who have studied art history for years to not know about Gee’s Bend. The 12 artists in the show have different stories about how they have arrived at this knowledge. For some of them, this exhibition was one of those turning points. Awareness of Gee’s Bend, a network and community – especially a community of women who are doing collective, economic, cooperative, political work – can be so instructive to artists here and now.

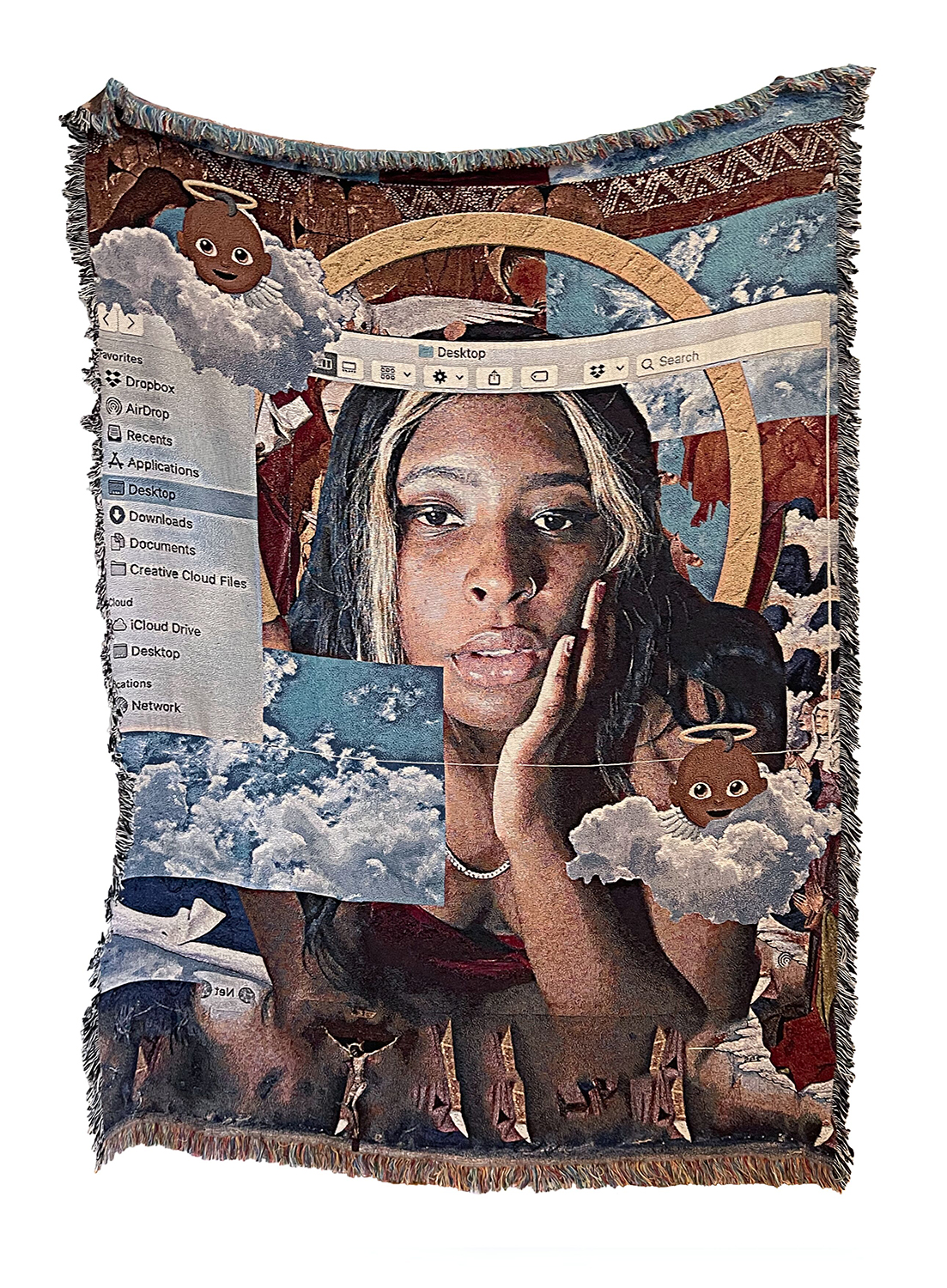

CH The show illustrates that wonderfully. The Jacquard loom played a crucial role in the development of early computing technology. One of the artists in the show, Qualeasha Wood, uses a Jacquard loom to make work that expresses the way, among other things, digital and material experience can’t be separated. Are there any other examples from the show that illuminate the connections between textiles and the digital?

LR Sadie Plant’s Zeros and Ones is an interesting text because it underscores the way that the history of computing and the history of weaving are deeply intertwined. There’s a great discussion about how the early computers were actual human beings. From the period of weaving as a technology, moving into what it is to embody computing – to literally be a computer. And who those people were, as labourers, often gendered labourers.

When we think about where those things intersect with American capitalism, it expands into a discussion about the machine. We know that this is race, gender and class history – the bodies that have been indicated as machines inside of capitalism, and how that has been instrumentalised to advance certain goals economically and otherwise. Thinking about the history of the pixel, we can consider a pixel as a stitch. What Qualeasha’s work shows us is that there are these interwoven, complex machinations that live inside of these histories and the ways we can analyse them.

The way that the digital intersects with our understanding of the material comes up as well in Tomashi Jackson’s work. Tomashi uses printing processes and the act of cutting to bring abstracted imagery into painterly form. We see it in Diedrick Brackens’ work as well; Diedrick is thinking deeply about the traditions of being a weaver. He often speaks with such care and vision about carrying on that history, really claiming it, like “I am a weaver”. Naming that as a category, taxonomy and designation.

This is important because these classifications have been segregated from one another in art history. The idea of being a weaver or artisan lives separately from this idea of being an artist. To allow those traditions to live in the same space and time is an important political act. And it is deeply reparative inside of histories that have done real harm work by forcing these categories to live separately without acknowledgment.

It’s interesting too to think about Tuesday Smillie’s relationship to the banner, a material that indicates a message and can exist inside of a space of protest but also in a parade. It can be festive, but it’s also a material of refusal, a moving architecture that reveals and deletes, or redacts information.

CH I was thinking about motion, too, about banners and flags and how some of the works in the show hang from the ceiling, and others invite movement around them in space and a looking into or through. Others lean or hang on the wall. Why is the motion of the viewer through the space important?

LR Typically in a group exhibition there are considerations about how each work can hold its own space, but I felt excited about bringing these different artists into dialogue with each other, and about how the curatorial framework could be less sterile and rigid. It was important to me that it not be displayed heavily on top of the work, but rather that the works themselves dictate how the framework should perform.

I was committed to this idea of what it means to splice and to stitch and to abstract an image, but also to create a new image by doing some of that remixing, and having the visual experience of the exhibition space allow for different sight lines to go literally through the work. To have opportunities where you can look through works into other works and begin to see the relationship between artists, and between media and materials. Speaking as a curator, I’m situated in the continuous intersection of art and technology, but I’m also deeply invested in performance, and the performance of objects. I think that objects are not objects; they are proxies for so many other things, and they’re always living and moving and dynamic in that way.

For that reason, the exhibition becomes about movement and movement research, encouraging people to look through and look up, look down and walk around. Actually, those are opportunities to come into a deeper awareness of our separation between body and machine. The relationship between a history of objecthood and a history of performance and movement.

CH In thinking about the artists and their different involvement with Gee’s Bend quilts, I saw that Diedrick Brackens is on the board of the Souls Grown Deep organisation. Eric N. Mack’s Proposition: for wet Gee’s Bend quilts to replace the American flag – Permanently was in the 2019 Whitney Biennial. And I think at least one of the artists in the show made work in homage to Gee’s Bend quilts specifically for the show. Could you talk more about the meaning of the quilts to the artists and their work?

LR Eric N. Mack, Tomashi Jackson, Basil Kincaid and Dawn Williams Boyd are artists who have been very pronounced about Gee’s Bend quilters being their ancestors. These are artists that are drawing on them in a direct familial kinship; they feel that very deeply. Other artists like Zadie Xa, Sojourner Truth Parsons, Anthony Akinbola, Eddie Aparicio and Genesis Jerez are in conversation with Gee’s Bend, in that there is an intersection with their work and also a departure from it.

Zadie Xa is Korean Canadian and is based in the UK. She creates work that often brings together a lineage of a feminist Korean history, exploring the language of a kind of feminist shamanism in Korean tradition. She is bringing together some of those traditions alongside a direct citation and celebration of Gee’s Bend. As you enter the gallery, you see one side of these amazing banners that are a more traditional approach to pointing to what the Gee’s Bend quilting practice looks like, and on the other side, her own life experience and tradition is in direct dialogue. These are things that the artists in very different ways are thinking about, and they are also bringing their own traditions, from inside their own diasporas. This is an integral part of how this can all be organic and keep living.

CH The Freedom Quilting Bee was formed by Gee’s Bend quilters at the height of the civil rights movement and played a big role in the development of that community. Tuesday Smillie is one of the artists in the show that makes work that references protest banners and queer pride celebrations. The theme of resistance and social justice is really strong in this show – is there a politics to quilting?

LR The question of politics stands inside of every one of the works that are in the room. For example, Dawn Williams Boyd is fearless and courageous in the ways she is taking a very traditional approach techniques that have been handed down across generations and applying them in an entirely new way by bringing in a conversation that engages American media and broadcast. These are really tender moments.

Diedrick Brackens’s work often engages head on with the ongoing HIV and AIDS crisis, shedding light on how Black and Latinx people are disproportionately impacted by these histories as they intersect with the social and cultural impact of processes such as gentrification. Having the exhibition sited in Chelsea, the apex of so many important histories and the enduring contributions of people of colour and queer people over time, makes that all the more resonant and urgent.

These artists are thinking about the ways that those different traditions and histories come into clashing conversation. They recognise that the process of production is always political, especially if you are coming from a historically oppressed, marginalized history. They are courageous, because they hold that space. Through their work and their machinic production, they are aware of themselves as producers and drivers of those technologies, and they think deeply about our relationship to labour through and beyond the artworld.

CH That’s an important aspect of this exhibition that goes all the way back through the history of the Gee’s Bend quilts. I’m thinking, too, about the intimacy of the quilts. You have described the show as ‘a love letter to the women of Gee’s Bend’. There’s a feeling here of reaching back through time and honouring the past and present of ancestors and lineages. I also thought of the AIDS Memorial Quilt, and I’m moved by the ways that quilts can address loss and underscore ideas of family and relationships.

LR That’s another big question, remembering the exact moment where I learned about the AIDS Quilt as a collective action. That was also something that came in my homeschooling, as in pedagogy at home. Also because I went to Quaker school; it was something that’s a big part of thinking about questions of social justice and civil rights. It’s a really sobering and necessary line to draw, when we think about these different models of collective work, cooperative work but also asking for a certain type of reparations. In many of these histories there is so much that has been taken. Within the context of the unfolding histories of civil rights, social justice inside of the United States, as much as there are victories that have been earned and hard-fought-for, they also continue to just be deeply eroded.

We’re in a situation now where it’s less than 48 hours since the Supreme Court reinstated racial gerrymandering in Alabama, which is where the Gee’s Bend quilters began. It’s important to talk about the fact that these things are inextricably intertwined, that this is a living history and not a romantic, purely aesthetic history. Something I think is dangerous is the idea that material can be studied purely as its form, rather than its context. It’s important to talk about how slippery that can be and to see the ways that artists take things back and reapply them. And hopefully give us some new proposals about what the world should look like.

CH Yes. There is a tendency to romanticise the quilts, which is often noticeable in how they’ve been written about.

LR I think it’s also really interesting that quilts are a material that is domestic and associated with a certain leisure or comfort. Part of what I think is amazing and instructive about Gee’s Bend quilts is that these are family trees. These are maps. These are archival documents. It’s important for us to not look at them as materials that should be fetishised and consumed through the lens of a static leisure. Rather, they need to be vivified and animated, always. That feels urgent to keep centre in this conversation.

CH You’ve spoken about the importance of not only including these quilts as essential to the story of modernism and abstraction but of restructuring the way we think about the canon and art history. Recently the Hilma af Klint exhibition at the Guggenheim brought up similar questions. But there’s this tendency to just say, “Well, let’s insert this person, or let’s insert this practice.” I think what you’re talking about is very different from that. Can you say more about how this exhibition can function as a turning point for how we think about contemporary art and art history?

LR It would be remiss to not point to another exhibition that is doing a different type of quilting that I also have been involved in, Kahlil Robert Irving’s solo show that is on view at MoMA. Thelma Golden and I worked together on that show, and one of the conversations that I kept going back to with Kahlil was this idea of where art and craft have been segregated. We are necessarily tasked in this next chapter to do better work to interrogate why that is. These are not passive decisions. The history of museums and many institutional sites is rising out of a history of class and gender and racial sciences. These are deeply volatile sites that are having to do restorative work, to navigate the fact that they have been complicit with a certain systemic failure of care in how they have been built and founded.

Kahlil’s exhibition is one of many steps, of many different artists across generations who are doing some of that work to restructure, reshape and refocus our view. I think it’s an exciting moment because of the fact that this exhibition does not exist in isolation, but in the same place and time as many things that are asking questions about how to do this work better and also how to ask the public, ask audiences, ask next generations to come into a different level of responsibility, stewardship and caring for this next chapter of art history. That is really what my great hope is.

CH I do think now is a time when this kind of change is really taking place. You see it with Black Lives Matter and monuments coming down. Recently a monumental Simone Leigh sculpture took the place of a Robert E. Lee statue in New Orleans. It’s a time of openness, and rethinking – with the #MeToo movement as well.

LR And in terms of how we conceive of art and artists, quilting can be instructive because it breaks apart the entire idea of what an artist is supposed to be. This romantic, problematic idea of mastery, of a genius isolated in the studio, as opposed to opening up a collective model that requires dialogue and discourse and exchange, and contribution that comes from many different points.

Feminism teaches that, Black history teaches that, Indigenous history teaches that, queer history teaches that. This exhibition is looking towards that future and hopefully it’s an opportunity to build and accelerate towards it. Because certainly the arts will not survive if the traditions that have been established from previous chapters of art history are the only ones that are recognised. We have to do some work of reimagining.

The New Bend is on view at Hauser & Wirth, New York, through 2 April