From London’s gallery-hosting project Condo to Colomboscope 2024 in Sri Lanka and Icelandic painter Erró, our editors on what they’re looking forward to this month

Condo London 2024

Various venues, London, 20 January–17 February

Condo, the gallery-sharing initiative founded by Vanessa Carlos of Carlos/Ishikawa in 2016, returns to London after a four-year hiatus. The month-long edition promises the ‘evaluation of existing models, pooling resources and acting communally to propose an environment that is more conducive for experimental gallery exhibitions to take place internationally’, which all sounds very nice if it wasn’t held in the city’s quietest and most financially-arid month – a kind of January Sales for the artworld. Luckily, a few swallows might yet a summer make. Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili’s photographic experiments enact dreams in sheer gauzes and gloss, ghostly prints – and feature in a group show for LC Queisser, Tbilisi (hosted at Hollybush Gardens); Alexandre Khondji’s polished metalworks bring menace in conversation with Christopher Aque’s washed-out prints on linen for Sweetwater, Berlin (at Maureen Paley); Vica Pacheco, a musical artist whose hermetic, almost pristine pieces layer and warp vocal and field recordings, will have a solo for PEANA, Mexico City (at Public Gallery). As ever, the scent of an art-crawl isn’t far off – try guzzling six galleries from Soft Opening to Union Pacific in just 38 brisk-footed January minutes. Alexander Leissle

Colomboscope 2024

Various venues, Colombo, 19–28 January

Curated by Hit Man Gurung, Sheelasha Rajbhandari (both Nepali artists and cultural organisers), Sarker Protick (a Bangladeshi artist and photographer) and artistic director Natasha Ginwala, Colomboscope 2024, the eighth edition of the Sri Lankan visual arts festival, is titled Way of the Forest and features work by more than 40 local and international artists. The forest, in this context, is simultaneously a site of extraction, ecocide and genocide, and of deities, ancestors and nourishment (not to mention, in the recent local past, a bloody civil war). Each of the curators comes with their own take on the operations of those polarities, as a chance to embrace the potential of art in a multispecies world. Nirmala Devi

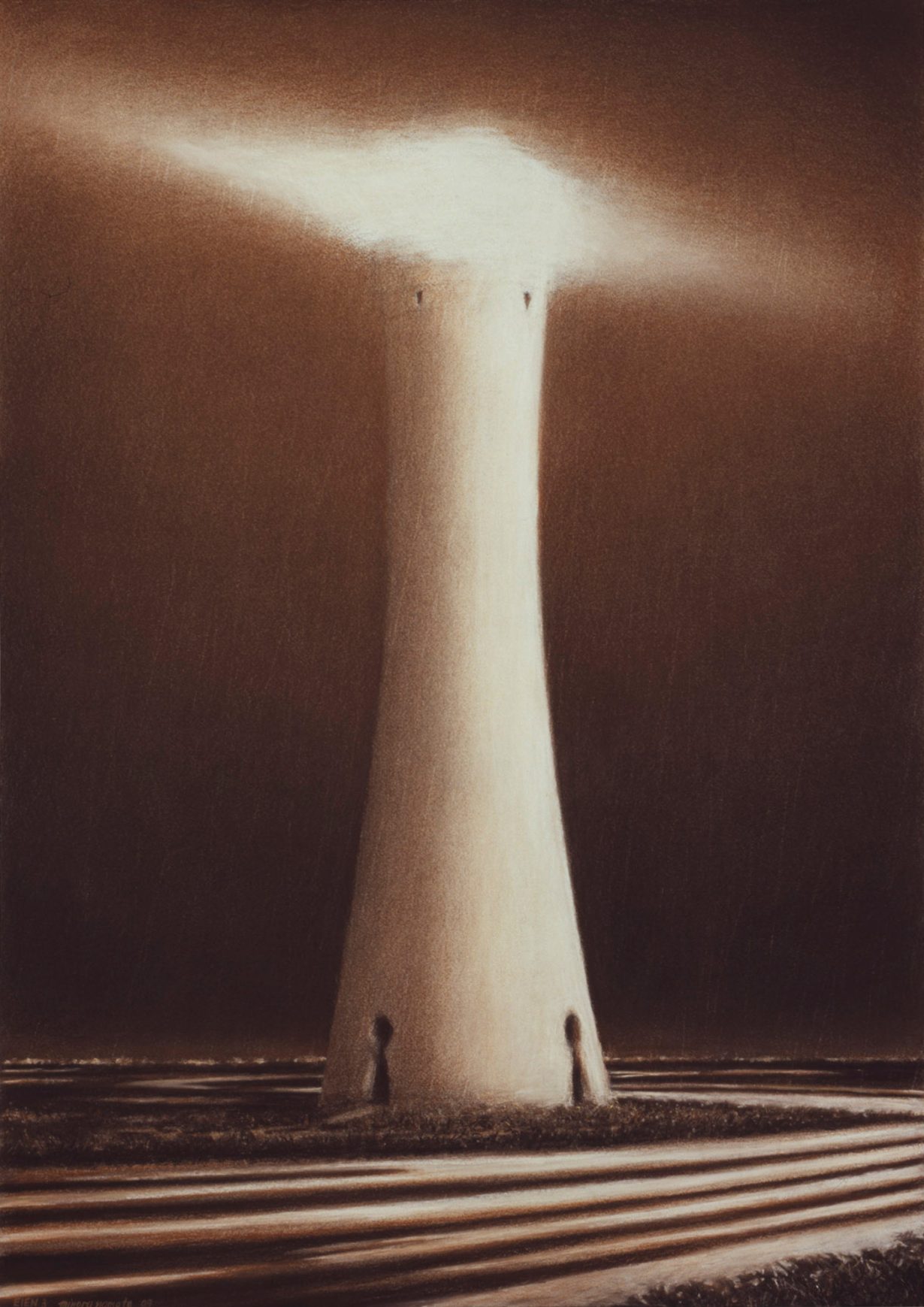

Minoru Nomata

White Cube, Seoul, 12 January–2 March

The surreal, fantastical architectural monoliths in Minoru Nomata’s paintings look at once like works of a Sienese master, vistas from a Victorian sci-fi or pieces of Soviet-era Constructivist monuments; Bernd and Hilla Becher’s industrial ruins (Seeds-14, 2004) or other-worldly footages of extraterrestrial contacts (Far Sights-3, 2009). Imbued with a stillness, as if existing outside of time, these protruding structures paradoxically gesture towards both the future and the past, and are perennially shown mid-construction. Having hosted a major survey show at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery earlier this year – whose title Continuum deals with time and continuity – the exhibition 映遠 – Far Sights at White Cube will explore the idea of space, distance and liminality. Yuwen Jiang

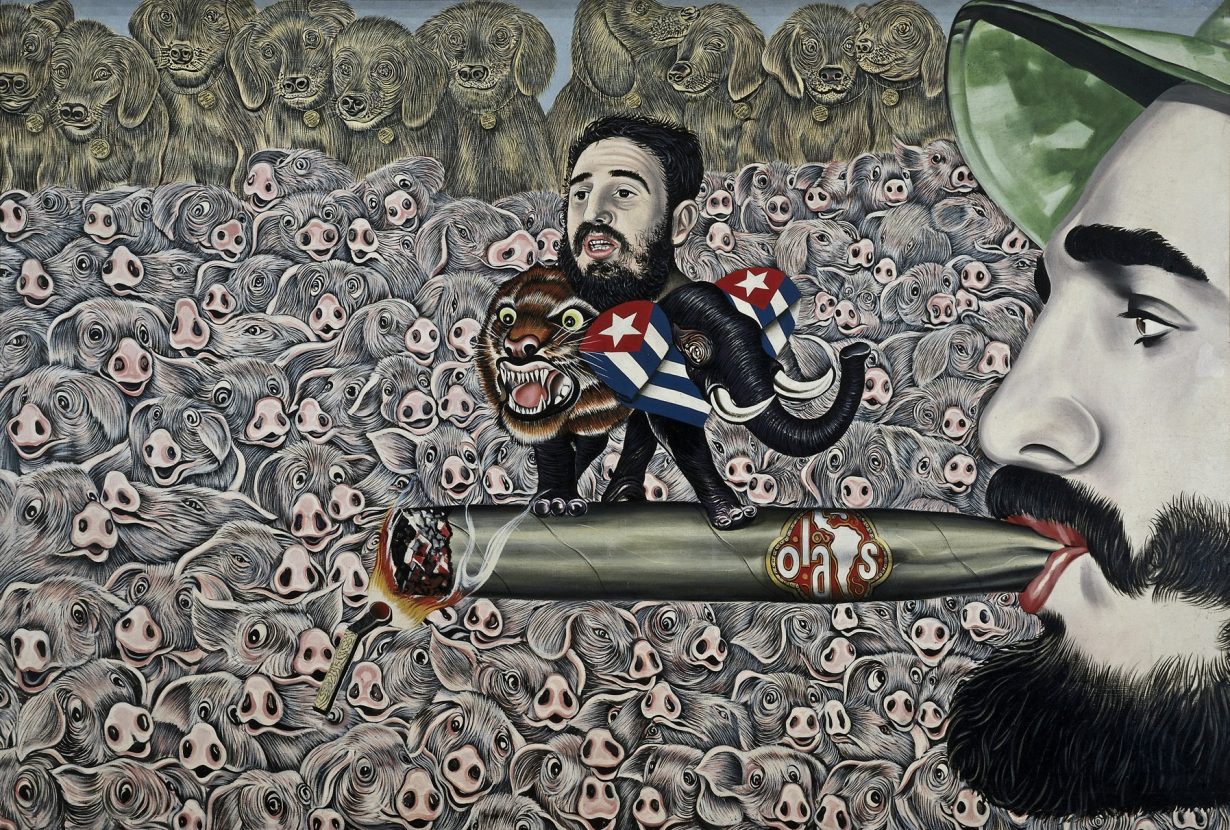

Gambit – Erró, Chronicler of Current Affairs

Reykjavík Art Museum, 13 January–12 May

The Reykjavík Art Museum rehangs its collection of Erró collages and paintings annually, each cacophonously rich canvas an amalgam of images from comic books, current affairs, celebrity and advertising, picking out different themes from the ninety-one-year-old Pop painter and collagist’s long career. While the likes of Captain America, Miley Cyrus, and Pikachu are mainstays of his work, the curator of this edition foregrounds the Icelandic artist’s enduring political interests (although Erró’s use of the man of the super-soldier serum, Wrecking Ball songstress and the Pokémon are not without commentary), packing together works made in response to global conflicts, political crises, atrocities, the rise of national heroes and international villains in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, from the horrors of the Nazi regime to the Cold War, US-backed coups in South America to the conflict between Israel and Palestine and apartheid in South Africa. ‘I feel like I’m a kind of chronicler, a reporter for an organisation that stores all the images of the world, and it’s my job to compile them’, he said of this work. His American Interiors series shows the likes of Red Army troops and the Vietcong invading all-American suburban homes, playing with the cliches and propaganda of US lifestyle media, while his Chinese Paintings utilise and satirise CCCP imagery. Oliver Basciano

Lacan, The Exhibition: When Art Meets Psychoanalysis

Centre Pompidou-Metz, 31 December 2023–27 May 2024

Fun fact: Jacques Lacan and his wife Sylvia owned Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du monde (1866). And kept it hidden behind a secret panel. Surprising? Probably not, given that Lacan was a hugely influential psychoanalyst who proclaimed that desire begins with the (m)other. Perhaps visiting the Centre Pompidou Metz this January will aid you in considering this fact, as the museum is going to stage the first large-scale exhibition dedicated exclusively to Lacan, his life, work and enduring influence in the arts on topics ranging from gender and sexuality to language and philosophical structures. Artists to be included span a range of eras and mediums, from pre-twentieth century masters such as Diego Velázquez and Courbet to modern (René Magritte, Marcel Duchamp, Maria Martins, Constantin Brâncuși) and contemporary (Maurizio Cattelan, Cindy Sherman and Jean-Michel Othoniel). The exhibition’s curators concede that Lacan was – and is – controversial for his hot takes, but as Marie-Laure Bernadac states in an interview ahead of the exhibition, ‘[Lacan] doesn’t necessarily provide answers, but he paved the way on all of these questions’. Marv Recinto

Mary Lucier: Leaving Earth

Cristin Tierney Gallery, New York, 19 January–2 March

‘A succession of discontinuous moments occur then disappear, without the elemental structure of sequence.’ These words, which feature in the text of the multichannel video Leaving Earth, were found by Lucier in the final journal kept by her husband, the late painter and writer Robert Berlind, who died of cancer in December 2015. Lucier, a pioneer of video art and video installation, has made work on the subject of loss and regeneration for many years. In Noah’s Raven (1993) she explores the imprint of catastrophic phenomena on the landscape with footage shot in Alaska, the Ohio River and the Brazilian Amazon; in Floodsongs (1998), the installation presents the people of Grand Forks, North Dakota, a town devastated by the 1997 Red River Flood, talking about their lives before and after the disaster. In this new piece, she turns to a more personal and intimate subject matter, which like the other works is defined by a sense of loss and grief, but also of warmth and humanity. Lucier has described Leaving Earth as a work where ‘words, pictures, and sound become interchangeable, not serving as descriptions but as a rumination on reality and a form of coping’. The above quote from Berlind’s journal continues ‘And yet… I forget to fear death’ in another form of tender affirmation of life – that is, a form of coping. Orit Gat

Pakui Hardware: The Burn

carlier | gebauer, Madrid, 25 January–2 March

Ahead of their Lithuanian Pavilion at next year’s Venice Biennale, Neringa Cerniauskaite and Ugnius Gelguda – the artist duo who work collaboratively under the name Pakui Hardware – bring their quasi-medical installations to Madrid. Aluminium structures seem to expel glass-blown ornaments like resinous boils and inflammations; igneous wall-based pieces bear the fossilised impression of medical instruments, pill blister packs and Sosnowsky’s hogweed (invasive, poisonous to human skin and, thanks to Stalin-era overproduction, rife in the Balto-Slavic world). Pakui Hardware, quite refreshingly, take scar tissue literally as a mode of investigation into our bodies, lives and environments. Alexander Leissle

Indian Ceramics Triennale 2024

Arthshila Delhi, New Delhi, 19 January–31 March

Having garnered critical attention for its first edition in 2018, the open-submission Indian Ceramics Triennale’s return was hampered by the pandemic. Now it opens with approximately 50 ceramic-based artists and collectives showing work under the literal and metaphorical theme of Common Ground: ‘The ground we walk on is uneven. We are separated by privilege, politics, motivation, experience and access to knowledge, yet we remain bound by a common humanity,’ the curators write. The works that will feature range from Kate Roberts’s ceramic wall ‘drawings’ to an installation by Neha Gawand Pullarwar that links Stoke-on-Trent, the centre of British pottery manufacture, and colonial Bombay/present-day Mumbai, once the centre of Indian cotton manufacturing and trade. Oliver Basciano

Raven Chacon

Swiss Institute, New York, 25 January–14 April

In 2022, Raven Chacon became the first Native American to win the Pulitzer Prize for music for his composition Voiceless Mass, performed on Thanksgiving at a Milwaukee cathedral like a haunting lamentation for the voiceless. However, prior to – or perhaps leading up to – this prestigious recognition, Chacon’s decades-long multidisciplinary practice has advocated for Indigenous sovereignty and environmental justice while querying hegemonies of colonial power. Swiss Institute will be staging Chacon’s first institutional solo exhibition and including 25 years-worth of sound, video, performance and sculpture alongside new commissions and iterations of previous works like Still Life No. 4 (2015). The original features recordings of Chacon beating an old Pueblo drum from the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center collection. This new version takes recordings Chacon created from beating a long-untouched Diné drum, owned by the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, and plays them throughout the Swiss Institute in an open question of the politics and implications of space. For Chacon, these unanswered prompts new avenues: ‘We should embrace incomplete knowledge’, he said in a 2023 interview, so ‘there’s always the new possibility to say something that’s never been said before.’ Marv Recinto

Lubaina Himid: Lost Threads

The Holburne Museum, Bath, 19 January–21 April

An installation made up of 400 metres of Dutch wax fabric displayed throughout the museum – on the façade and in the galleries alongside the museum’s permanent collection – in Lost Threads the Turner Prize winner reflects the loaded histories that materials can carry within them. Just the name of the fabric Himid uses, Dutch wax, exposes its complex history: these textiles, recognised in contemporary culture as African cloth, are interwoven with colonialism, as the process of making this cloth was originally influenced by batik, a Javanese method of cloth dying that the Dutch colonisers of Indonesia brought back to Europe and then to West Africa along the transatlantic slave trade route. Lost Threads was first shown as part of the British Textile Biennial in 2021 in the barn of Gawthorpe Hall, a sixteenth-century country house in Lancashire. ‘When I develop creative interventions in historical buildings, I’m doing a lot of the work with fabric or found objects, but the building also does a lot of the work’ Himid has said about the work. The installation weaves through another layer of knowledge that is added on top of the site in which it is shown, a reminder that the complex histories of materials, objects and people are always present, especially in sites like historic homes and museum collections. Orit Gat