From Rory Pilgrim in London to Tenzing Dakpa in Kolkata, our editors on what they’re looking forward to this month

Tadáskía

Museum of Modern Art, New York, 24 May–14 October

The breakout star of the last Bienal de São Paulo gets her New York debut with this commission, curated by the Studio Museum in Harlem’s Thelma Golden. In the Brazilian version she showed her loose-leaf book Ave preta mística (Mystical Black Bird, 2022), following a flight through a dreamlike world, each page pinned to a painstakingly applied immersive pastel mural on the walls and ceiling of the space. In the centre of the room: three sculptures made of bamboo, straw and cattail, with offerings of fruits placed in front of them. For the visitor, it felt like entering a prayer room in which the artist was meditating on how subjects are formed through scraps of identity, half-remembered histories and family tales; personhood ultimately a mutable, evolving creation. Oliver Basciano

Rory Pilgrim: pink & green

Chisenhale Gallery, London, 17 May–21 July

Multimedia (in the sense that he works across many different mediums, rather than activating a visual, sonic and experiential maelstrom) artist Rory Pilgrim’s work tends to involve the activation or creation and empowerment of communities in order to effect societal change. Their 2022 project RAFTS included a filmed concert, community drawings, meditations on a raft’s symbolic history and relevance, while evoking Britain’s ‘small boats’ migrant crisis – the extinction (rather than solution) of which is currently consuming the governing Conservative Party; the nation’s mental-health crisis and more general systemic inequalities (which the Conservative Party is desperate to maintain). Following their Turner Prize nomination last year, Pilgrim comes to the Chisenhale to present a work that ‘rethinks the emotional and ecological impact of law’, the artist’s engagement with communities on the Isle of Portland, and features a screenplay, live performance and music. Nirmala Devi

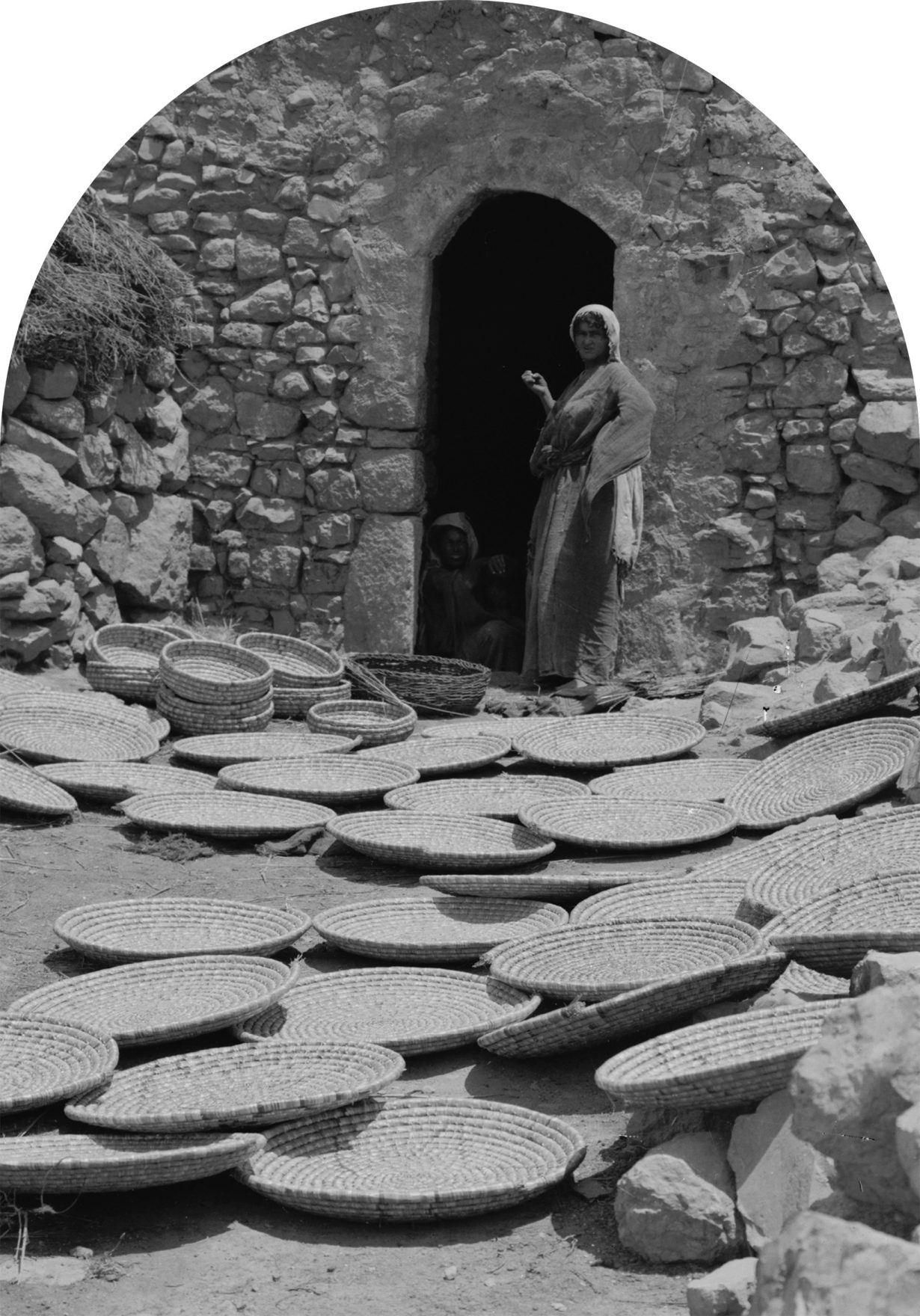

Dima Srouji: Charts For A Resurrection

Lawrie Shabibi, Dubai, 7 May–6 July

On a canal close to where I live, I sometimes pass a small group of people who are combing the shallow depths of the water with strong magnets. They’re in search of abandoned metal artefacts to repurpose, sell on, or occasionally display ornamentally nearby: twisted bicycles, mangled boat engines and all sorts of strange ephemera coated in a thick layer of rust. These are far from treasures exhumed from the deep but they reveal a desire to look beneath the surface, to bring up from below items left undisturbed for years and assign them new meaning. In the work of Palestinian-born artist, architect and researcher Dima Srouji, who is interested in the role of ordinary objects in identity, place and displacement, another kind of imaginary archeological site is activated. At Lawrie Shabibi in her first solo exhibition, she displays partially excavated hand-blown glass vessels in a nine-square grid installation, as if the digging were midway through; the ghostly glass replicas made by the artist stand in for the original ‘grave goods’ pulled from ancient tombs by western archaeologists in Palestine and Egypt throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. A series of photographic prints on aluminium bring into grainy focus the local ‘basket girls’ who were hired alongside the archeologists to extract artefacts from the ground that they themselves had cultivated for centuries, pulling from it their own heritage and collective memory for others to keep. Louise Benson

The Last Cage Down

The Mining Art Museum, Auckland Project, Bishop Auckland, 3 May–6 October

There’s a fair deal of art being made that attempts to memorialise history – witness, for example, the current Venice Biennale, with its emphasis on artists making images that recall and narrate the colonial-era struggles of Indigenous peoples. Political history gets forgotten quickly, and The Last Cage Down recalls a moment in British politics many in today’s neoliberal present would prefer everyone forgets. The 1984-85 miner’s strike was a turning point for British society in which unionised mine-workers confronted Margaret Thatcher’s conservative government, intent on closing down what was left of Britain’s coal mining industry – part of Thatcher’s ideological crusade to impose free market capitalism on Britain and break the power of the trade unions. The bitter yearlong strike was marked by violent confrontations between picketing miners and police, in particular the ‘Battle of Orgreave’ of 18 June 1984, in which 5,000 miners fought running battles with 6,000 drafted-in police, outside of the Orgreave coking plant in South Yorkshire. Forty years on, this show of paintings and sculptures by local artists, many of whom had been miners at the time, bears witness to the personal and collective experience of the strike, and its aftermath. As exhibiting artist Barrie Ormsby told Newcastle’s Evening Chronicle, ‘the miners’ defeat was the first domino to fall, knocking down the collective efforts of working people one by one – from dismantling trade unions to zero contracts. The strikes began 40 years ago but the impact is still felt today.’ J.J. Charlesworth

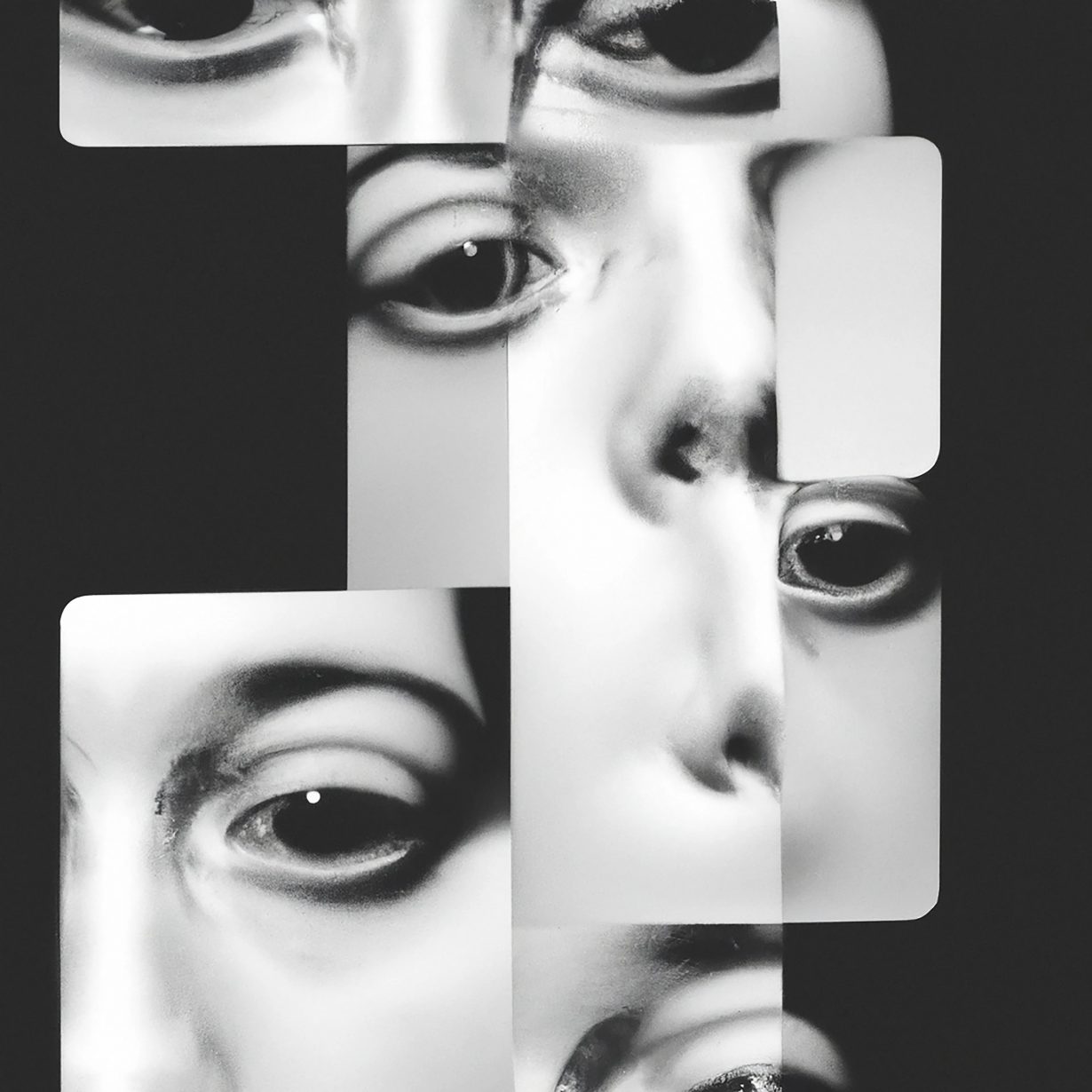

Photography Through the Lens of AI

Foam, Amsterdam, 31 May–24 August

It would be easy to use ChatGPT to write this preview. Maybe it is. The increasing difficulty of differentiating between what’s human-made and what’s machine-manipulated is, in part, addressed in Foam’s latest multifaceted project Photography Through the Lens of AI. The differentiation is made more complicated when you consider that, in most cases, humans still have to implement the use of technology – for whatever task its assistance the tool is required – in the first place; in the case of photography, technology has long been used to manipulate images, from chemically-produced photos in darkrooms to the use of Photoshop, and at present, an AI-generated image doesn’t simply come into being of its own accord. Yet. The bigger issue tackled in Photography Through the Lens of AI, which includes two exhibitions, a special-focus magazine and a ‘digital presentation’ on its online platform, is how AI is influencing the way in which images are conceived and perceived, and whether this marks a shift in photographic practice. The lines between human- and machine-creativity become blurred in the group exhibition Mirror Mirror, which ‘explores the intersection between art, technology, and society, highlighting how the recent advancements in AI impact our relationship with images, ourselves and our perception of reality’. Alongside this, Paolo Cirio presents a solo exhibition titled AI Attacks, which focuses on how AI systems and the use of large datasets impacts societies – particularly when it comes to the technology’s misuse ‘by (governmental) institutions and in public spaces’. If you were told the prompt for this text included an instruction to make it 300 words, would you believe it was authored by a bot? Fi Churchman

Tenzing Dakpa: Weather Report

Experimenter, Hindustan Road, Kolkata, 25 May–27 July

‘One’s sense of self is inseparable from the spaces we create’ said India-born, second-generation Tibetan photographer Tenzing Dakpa of his best-known body of work, The Hotel, a presentation of which was one of the standout displays at the last Kochi-Muziris Biennale. This lyrical work (begun on return visits after the artist left home in 2004) documents the establishment (people, décor, furnishings, animals and plants) in Gangtok, Northeast India, that his parents (and, necessarily, the rest of the family) ran – both a home and a workplace, a transient space and a permanent dwelling, personal and impersonal at one and the same time. At Experimenter’s Hindustan Road Gallery he presents two bodies of work, Manifest and Weather Report, which document human and non-human impacts on the natural environment. The first depicting the aftermath of forest fires in North Goa (allegedly started by humans trying to ‘tame’ the local ecology); the second the effects of climate, seasons and time of day (what a philosopher such as Immanuel Kant would suggest are the things that no human can control). Dakpa, however is more interested in Buddhist philosophies, preferring to reference ‘bardo’ – the liminal place in which consciousness deals with the end of one life and the beginning of the next. Nirmala Devi

Intimacy rarely makes sense of things

Pond Society, Shanghai, 15 May–15 June

For the cultural theorist Lauren Berlant, intimacy was not a kiss or a hug between lovers (or not just that), but the moment in which internal desires meet wider society – closer to solidarity but with a greater emphasis on care and identity. Berlant’s amorphous idea ties the work of five western artists, brought together by curator Kyla McDonald, in their own public embrace. Lenz Geerk’s series of acrylic paintings, voyeuristic scenes of a couple in their apartment, provide the most conventional image of closeness (though they are dark and creepy); while Cathy Wilkes’ installation Untitled (2022-23) plays on the uncanny alienation of capitalism, and Joanna Piotrowska’s photographs, of adults in dens built from their own furniture, as if sheltering from an air raid, destabilise the sense of home. France-Lise McGurn and Caragh Thuring’s paintings, the former in which bodies intermingle with pop references, and the latter in which the human form is interchangeable with the architecture and urbanism that surrounds it, instead suggest that the intimate is ultimately a moment of friction between the self and beyond, a possible catalyst for change. Oliver Basciano

Danh Vo

Various locations, Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Brussels, 14 May–1 June

Vietnamese-born, Denmark-raised, Mexico-based artist Danh Vo has always presented a uniquely personal take on the grand narratives that shape our present – among them colonialism, globalism, and the processes of the adaptation and birth of cultures. Commissioned by the Kunstenfestivaldesarts (an international festival of performing arts) to present a new work in Brussels the artist has taken a 1970s Fiat hearse and converted it into a mobile flower shop, which articulates some of the universal vocabularies of death and rebirth. The mobile installation will pop up at various locations around the Belgian capital where visitors and residents can purchase unique bouquets that combine mechanical and floral elements, all of which are the result of a process involving young, trainee mechanics, art and floriculture courses, creating communities as a result of both the production and the consumption of the artwork itself. Nirmala Devi

Summer Show

Fondation Beyeler, Basel, 19 May–11 August

Stodgy and dusty old museums, full of static artworks that just sit there (or hang there) while you just look at them, are out, and not where it’s at. Which, if you’re an august institution with a fine (but fairly object-based) collection like Basel’s Fondation Beyeler, could be problematic. So this summer the Beyeler shakes things up with Summer Show, a project in which the entire museum and the surrounding parkland is taken over by a who’s who of contemporary art’s smart-set, including Arthur Jafa, Phillipe Parreno, Rachel Rose, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Marlene Dumas and quite a few others. The organisers, who include Parreno, artist Precious Okoyomon, the Beyeler’s top-man Sam Keller, curators Mouna Mekouar and Hans Ulrich Obrist, describe it, somewhat inscrutably, as ‘a dynamic rather than static proposal, an evolving ontological project that mirrors the complexity and diversity inherent in bringing together distinct artistic voices under one umbrella’. Modelled on such ambitious multi-form exhibition-performance hybrids as Obrist and Parenno’s Il Tempo del Postino, Summer Show looks set to scramble habitual exhibition conventions, with artists invited to intervene across galleries, gardens and terraces as much as the box office, shop, foyer and other spaces. The perfect antidote, then, to wandering the endless aisles of gallery booths at Basel’s other institution, Art Basel art fair, which opens its doors a month later. J.J. Charlesworth

Margaret Leng Tan: Dragon Ladies Don’t Weep

Queen Elizabeth Hall, Southbank Centre, London, 24 and 25 May

Video projections, 51-cm-high toy pianos, recorded text, spoken word performances, prepared pianos and miniature megaphones – these could only constitute the ‘orchestra’ of experimental music superstar Margaret Leng Tan, for whom the toy piano has become the primary instrument for delivering her version of the musical avant-garde. Peanuts creator Charles Schulz was – obviously – a fan, while Tan was also a frequent collaborator with John Cage during the last decade of his life and, later, with American painter Jasper Johns. The New York-based Singaporean’s instruments in past performances have also included cat-food cans and soy sauce dishes; she also holds the distinction of being the first woman to gain a PhD in musical arts from New York’s famed Juilliard School. Dragon Ladies Don’t Weep is an autobiographical journey through Tan’s career that incorporates themes of ‘memory, time, control and loss’ as well as the artist’s struggle to control her OCD: “Music is all about counting.” She told The Guardian a couple of years ago. “OCD is all about counting. It is a marriage made in heaven.” Nirmala Devi