Baggy terms such as ‘Global South’ and ‘Global Majority’ are useless, because you can’t address what you can’t describe

Half an hour into my first Equality, Diversity and Inclusion meeting, I was asked by a well-meaning white colleague to stop saying ‘people of colour’ and to replace it with the ‘correct’ term: ‘member of the global majority’. Suitably chastised, I hung my global majority head in shame (even though ticking the ‘Mixed-Other’ box all my life had hardly made me feel part of any majority). But even then I couldn’t help wondering if the language we use to navigate identity might be obscuring more than it reveals.

Terminology has always played a central role in how we understand global structures of power. From ‘colonies’ to ‘Third World’ to ‘Global South’, the lexicon used to describe the inequitable distribution of wealth and power has evolved alongside the systems that create the haves and have-nots of our world. And yet, even as we adopt more inclusive terms (I grant that ‘person of colour’ troublingly implies that the ‘person’ bit without the qualifier is, de facto, white) these can fail to capture the root causes of the structures they purport to describe, or worse, can serve to sugarcoat them.

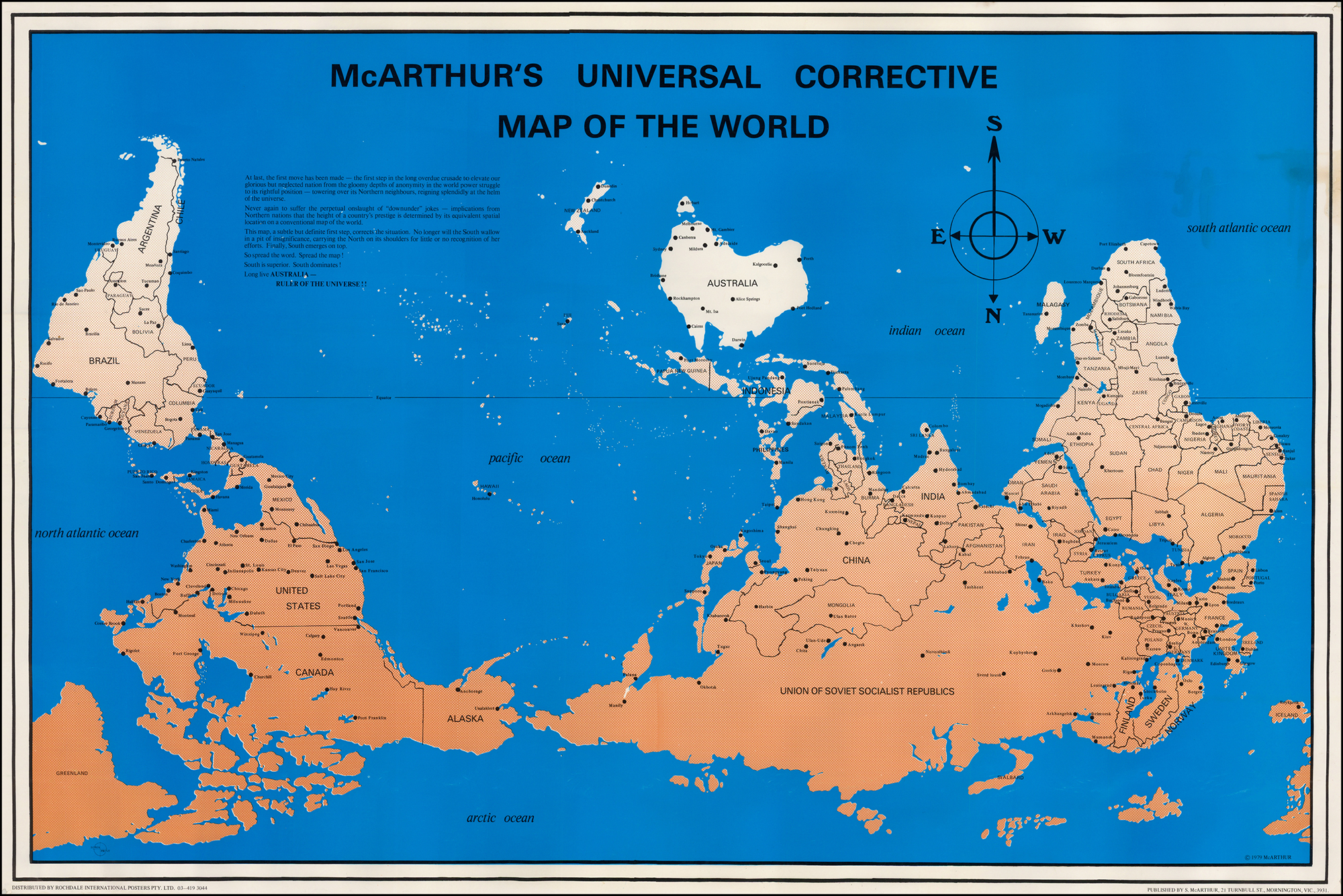

Take ‘Global South’. Coined by American scholar and activist Carl Oglesby in 1969 to highlight disparities between nations that industrialised through imperial pillage and those whose development was derailed by it, the term is criticised by scholars of decolonial theory for cultural flattening. Marxists propose the term ‘global proletariat’ instead, but the jury is out on who that refers to in primarily agricultural countries. During the 1950s and 60s, ‘Third World’ as a positive term of association had African, Asian and Latin American advocates, but their attempts to turn this into real economic and political alliances did not survive US interventionism and the oil crisis of the 1970s.

As it stands today, emptied of Oglesby’s economic words like ‘pillage’ or ‘imperialism’, the term ‘Global South’ is a catchall. Those who celebrate it as a shared geopolitical orientation impossibly group super-rich states like Qatar, the UAE and Singapore, as well as rising juggernauts like China or India, alongside the likes of, say, Lesotho or Yemen. If it captures neither current power dynamics nor real material differences, the term loses analytical usefulness.

It is equally unhelpful as an adjective – ‘a Global Southern country’ – because this ignores internal divisions of ethnicity and class. The interests of a subsistence fisherman from the Niger Delta and a Lagos property tycoon, or an Indigenous Amazonian and a Brazilian agribusiness executive, are opposed – live as they might within the same national borders. ‘Global South’ makes it harder to see how local elites (often beneficiaries of colonial legacies) function as power brokers. Given that the colonial officer of yesterday is now the local overseer at the Bolivian lithium mine or the Nigerian oil field, that is not good enough.

So, what could better serve our understanding? Maybe it’s more accurate to speak of ‘the neo-colonised world’: a term that captures how historically extractive relationships persisted and mutated. Today’s extractive empires are corporate and financial, not just national or hemispheric. What binds the neo-colonised isn’t always geography, but their exposure to systems of debt, land dispossession and resource plunder sanctioned by global institutions and local enforcers alike.

If our words to describe racial, sexual and gender identity have become more nuanced, our vocabulary to describe global inequity needs equal attention. Caring about our words isn’t pedantry; it’s about clarity of purpose. We can already see the dark consequences of language that obscures a power relation by calling it a ‘natural’ divide; that women’s ‘natural’ task is reproduction and therefore should not involve choice is a common refrain of misogynists today. If we use vague terms for global exploitation, we risk similarly naturalising the structures that uphold them – and weakening the solidarities that resist them.

‘The neo-colonised world’ is not a perfect suggestion, but it does resist the implication that global inequities are an accident of place. If our words can’t trace the lines of exploitation, we won’t know where to direct our political energies. Or as the comedian Vidura Bandara Rajapaksa puts it: “People used to group us in Sri Lanka under the ‘Third World’. It was a little mean, but at least it showed how the world viewed us. Now there’s the nicer term ‘the Global South’, which makes it sound like it was geography that fucked us.” It wasn’t.

Sarah Jilani is a lecturer in postcolonial literatures and world film at City, University of London

From the May 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.