What do voyages into the unknowable depths of the ocean reveal about the human impulse to confront the horrors submerged within ourselves?

‘WORLD’S LARGEST METAPHOR HITS ICE-BERG’, the front-page headline of a 1912 newspaper hollers; ‘TITANIC, REPRESENTATION OF MAN’S HUBRIS, SINKS IN NORTH ATLANTIC – 1,500 DEAD IN SYMBOLIC TRAGEDY’. Despite the grainy photograph and the period fonts, though, this isn’t a real report, but a 1999 mock-up by the satirical newspaper The Onion. I thought about it after the more recent doomed voyage of the Titan submersible, which imploded on a trip to the shipwreck of its namesake on the seabed of the Atlantic last week. Along with the extended information vacuum of the search (perfect for speculation among Twitter punters, TikTok creators and TV ‘experts’), and the almost cartoonishly appalling violence of its ending, one of the reasons that the Titan story gripped the public imagination so strongly was surely that people got to make that same joke all over again. It was too good to be true: the Titanic was already a morality tale about the folly of rich people claiming technological mastery over the oceans, laden with dramatic irony, and now they’d gone and done it again! The jokes took on a recursive quality: would there be submersible tours to visit the wreck of the submersible tour?

Those who fail to learn the lessons of history are, of course, doomed to repeat them. If the Titan’s passengers were so fascinated by the significance of the Titanic, the punchline went, then perhaps they shouldn’t have forgotten the missteps that led to the tragedy. But I think any failure to learn the Titanic’s historical lessons wasn’t down to forgetting, but down to obsessive remembering – and re-remembering. This accident happened partly because the Titanic is a crime scene to which we just can’t help returning; a grave that we just can’t let rest. Even before James Cameron’s 1997 film, it had already become a story about class and gender. But the deep sea is also a profound, long-standing human metaphor for our own psychic, murky depths; the submerged parts of ourselves that we can never quite seem to fully leave behind, compelled instead to repeat and revisit. As Ted Hughes put it in his poem about fishbone flotsam, ‘Relic’: ‘Time in the sea eats its tail’. For Sylvia Plath, the sea carried particular emotional resonance after moving inland as a child following the death of her father; in ‘Full Fathom Five’, written three years prior to ‘Relic’, she describes how the ‘unbeaten channels of the ocean’ figure forth ‘origins unimaginable’.

The 1997 Titanic movie gets at this with a bookending frame narrative, in which the modern-day, elderly protagonist Rose joins a research expedition to visit the site of the wreck, and recounts her ill-fated story. The deep-sea explorations of the researchers mirror Rose’s own excavation of the memories which, as the final shot of her bedside photographs suggests, moulded the rest of her life. In one scene, the younger Rose is shown making a risqué joke about how a fellow passenger’s preoccupation with the ship’s size might suggest an interest in the work of Dr. Freud. ‘Who is this Freud?’, the man asks; ‘is he a passenger?’ The moment is meant to characterise Rose as a modern, enlightened free thinker among moneyed dullards. But it’s also a hint that, as much as it’s about the sinking, the Titanic movie is about how best to account with the past selves that shape us in the present. Freud himself, of course, enthusiastically seized upon the paradoxical spatial logic of downward, inward exploration to explain his theories of deeply submerged aspects of the self.

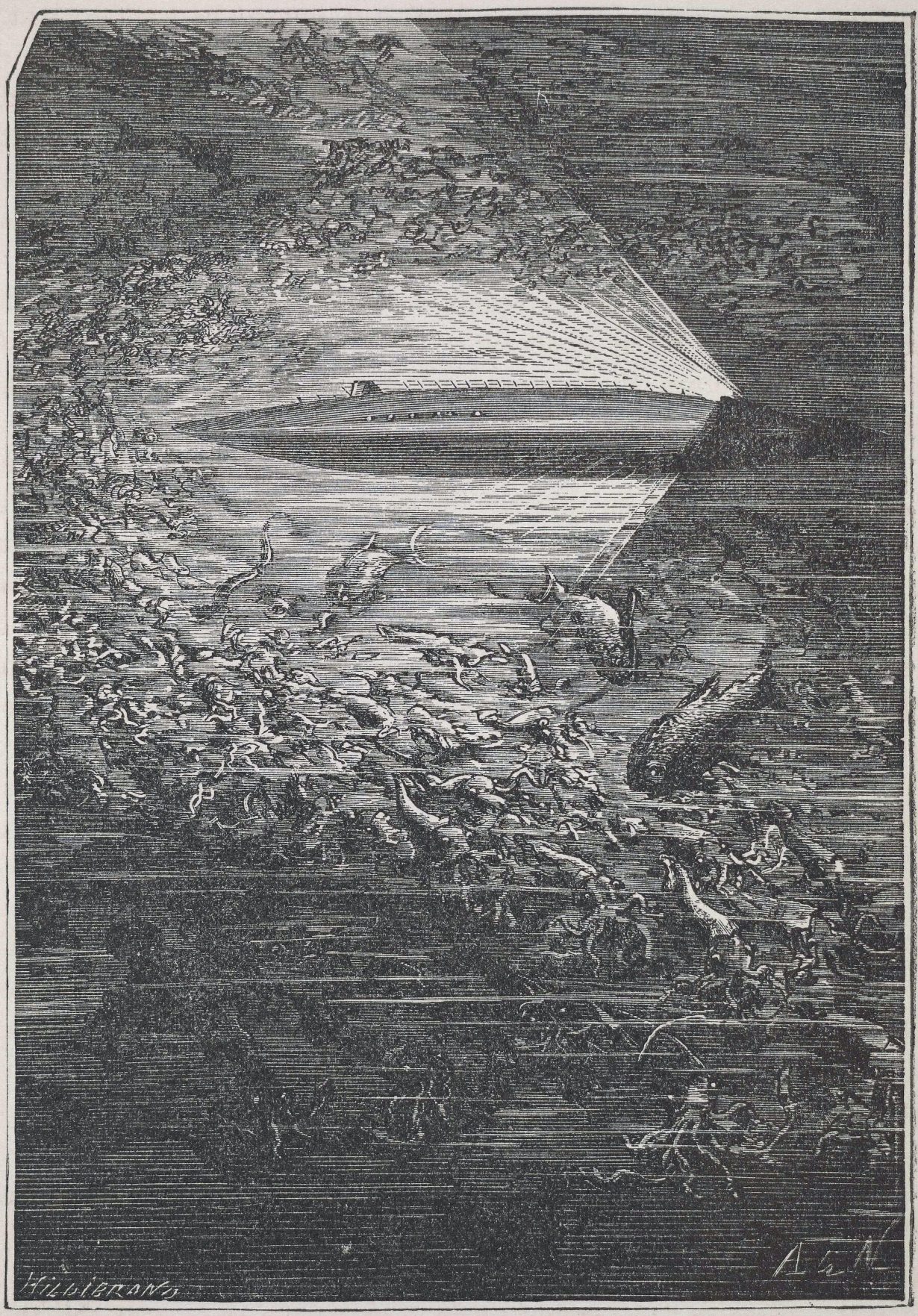

Decades earlier than Freud or the Titanic voyage, though, the cultural connection between deepest seas and darkest selves had already been articulated by Jules Verne in his 1872 novel, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas. With its giant squids and trips to Atlantis, the book has gained a justified reputation as a ripping, steampunk adventure yarn. But hardly anyone (with the exception of critic Sian Cain) seems to share my own sense of it as essentially a harrowing psychodrama. Its protagonist, Captain Nemo, takes to the ‘Nautilus’ submersible as a recluse from a civilised society he fervently, and mysteriously, despises. Nemo kidnaps our narrator, Pierre Arronax, with whom he establishes an uneasy intellectual and homosocial bond. But the longer he spends in the deep, the more Arronax’s narration is couched in terms of the threat of a descent into madness. As the episodic narrative reaches its denouement, his perception of reality begins to warp and bend under pressure: ‘I was troubled with dreadful nightmares… The clocks had been stopped on board. It seemed, as in polar countries, that night and day no longer followed their regular course. I felt myself being drawn into that strange region where the foundered imagination of Edgar Poe roamed at will.’ But whereas the key analogy of Poe’s Gothic horror is between spatial enclosure and psychological interiority – the trap door, the closet, the locked-up room – the terror of Verne’s novel derives from depth: the limitless vastness of it, and the submerged things that it conceals, both inherently of us and yet deeply other to us.

If Twenty Thousand Leagues is a pas à deux of the masculine psyche, taking place between Nemo and Arronax, British writer Julia Armfield’s 2022 novel Our Wives Under the Sea also positions itself in that tradition of submarine Gothic psycho-horror (‘The deep sea is a haunted house’, runs the novel’s opening line) but transposes it to the relationship between Leah, a marine biologist, and her wife Miri. The split narrative perspective switches between the months that Leah spends trapped on a submersible expedition gone awry and her return to the home she shares with Miri. It’s a far odder story than Titanic or Twenty Thousand Leagues, slippery and diaphanous like the deep-sea creatures with which Leah is obsessed. It’s also stalked by proper Lovecraftian darkness: not only Cthulhu-like sea monsters, but also the more acute terror of the realisation that we are all, ultimately, doomed to lose what we love. But again, the animating symmetry is between the sea and us. One of the novel’s two epigraphs is a quotation from Moby Dick (the other is from Jaws): ‘consider them both, the sea and the land; and do you not find a strange analogy to something in yourself’, Herman Melville writes; there is in all of us an island ‘encompassed by all the horrors of the half-known life’.

Armfield’s queer love story is one kind of reclamation and remaking of Melville’s analogy. Another, more grimly literal in origin, is the late American poet Lucille Clifton’s ‘atlantic is a sea of bones’. The bones, Clifton writes in the poem, are ‘my bones’, belonging to enslaved ancestors who were thrown off boats crossing the Middle Passage: ‘some women leapt with their babies in their arms. / some women wept and threw the babies in.’ Now, ‘maternal armies pace the atlantic floor’. In this Black cultural imaginary, linked to afrofuturist legends of ‘Drexciyan’ babies who swam from their mother’s wombs, the deep sea hosts psychic wounds that are not only personal but ancestral.

Today, in a different context, the oceans remain the site of death by racialised violence. Four days before the Titan imploded, a fishing boat carrying an estimated 700 migrants sank in international waters in the Ionian Sea, killing the majority of people on board, including up to one hundred children. As many have pointed out, the level of media interest in and sympathy for the people killed in the two incidents was predictably uneven. There was extended coverage of the lives, the families, the interests of the Titan’s passengers. Does anyone know much about the children who died in the Mediterranean? If the sea is a symbol of the hurt we carry deep within ourselves, it is also one – more urgently – of the violence we are capable of inflicting upon one another.

James Waddell is a writer based in London. He is a PhD student at UCL, researching distraction in 16th-century literature