In the artist’s exhibition at Pace London, Liquid a Place, we begin to to think of water as space of resistance, liberation, terror, conflict, oppression, refuge, extraction and pollution

New York-based Torkwase Dyson’s upcoming exhibition at Pace London offers something of a paradox: the show is titled Liquid a Place, dominated by three large, imposing, mainly black solids. There’s an immediate disjuncture between expectation and consummation: between what you are conditioned to think by the freeflowing implications of the title and what you sense from these static, solid objects. Confusing? Well, life is. You’re gonna have to think a bit. Dive in. Explore.

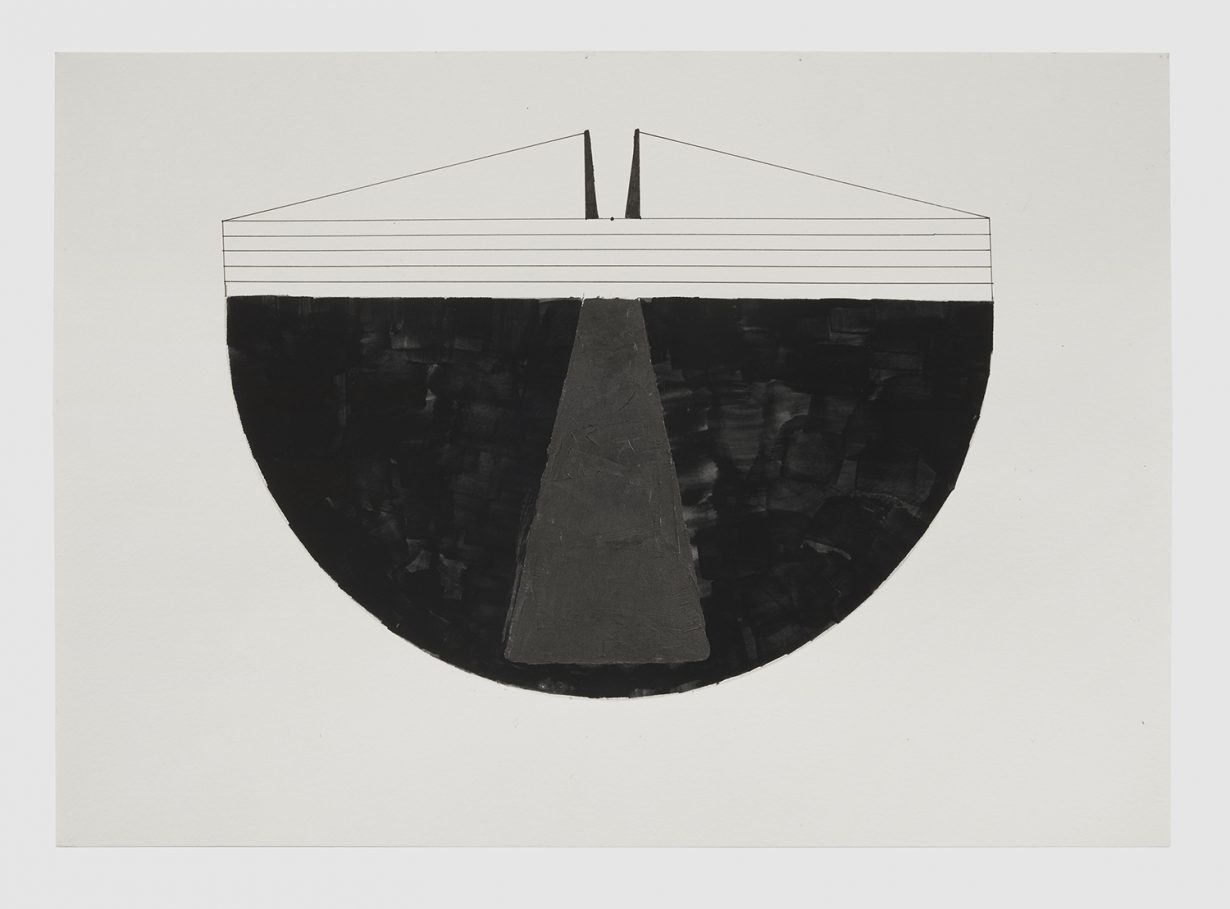

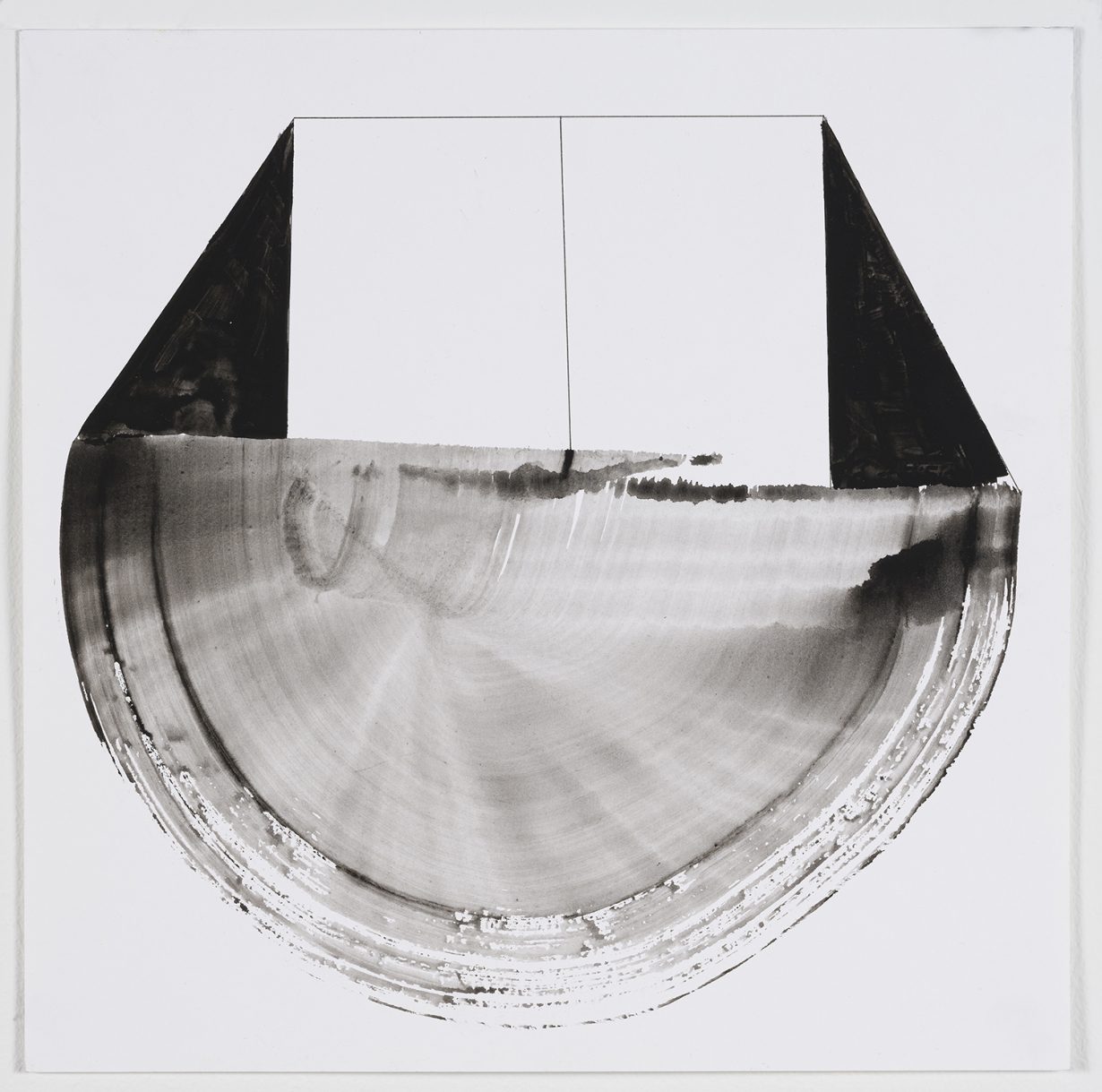

The sculptures, which are semicircular in form, rest on the centre of their arcs with a triangular void running along the sagitta. Perhaps the void is a gateway, perhaps a shelter. As a whole, though, it generates a sensation that is curvy and leggy – for those of you not interested in the purer geometry. It is as much anthropomorphic as it is architectural. The sculptures are accompanied by a sound installation, and over the opening three days of the exhibition, the space and the sculptures will be activated by a series of performances, featuring dancers, poets, artists, curators, performers and academics. A network of Black bodies assembled during research trips to and into London and from among the artist’s previous collaborators. Other bodies that will introduce new or shared trajectories in response to Dyson’s work. Ricochets, if you like. An element of instability or fluidity in contrast to the stability embodied in the sculptures themselves. Even Dyson is unsure about how, precisely, that will flow. That triangular space, its interior surfaces coloured white, is scaled to accommodate the height of the tallest performer (188 cm): a potential container of sorts, a kind of angular womb.

Governed by a spirit of openness, generosity and curiosity, Dyson’s work is generative in nature: the London exhibition is also accompanied by an album, a limited-edition dubplate featuring collaborations with and new works by Chicago-based DJ and producer Ron Trent, as well as music by London-based artist Gaika and Yoruba-American artist Ase Manual – its form a tribute to the means by which Black music has been disseminated across African and Caribbean diasporas in the UK. And at a time when, post virus-enforced seclusion, we are both longing for physical encounters with artworks as discrete objects and refiguring our expectations of art as something that does something – or has agency in whatever it is we mean by ‘the real world’ rather than sitting aloof or apart from it – Dyson’s work seems perfectly to fit the moment.

While she is fundamentally a painter of broadly abstract works, Dyson’s output spans a wide range of media, including performance, sound, sculpture and architecture. 1919: Black Water, a 2019 exhibition at Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery at Columbia University, featured drawings, paintings and sculptures created in response to the centenary of the ‘Red Summer’ of white-supremacist terror and racial riots across large parts of the US. Dyson’s inspiration derived from the history of Eugene Williams, a Black teenager who was stoned by a white man and who, as a result, drowned in Lake Michigan (Dyson grew up nearby). The riots that followed the Chicago police’s refusal to take any action against Williams’s attacker left 38 people dead and 527 injured, with a thousand black families made homeless. Dyson, through a series of abstract paintings and drawings that incorporate the languages of geometry, mapping and sometimes encrusted accumulations of pigment and colour washes and collaged flotsam and jetsam, which are then mirrored on the dark reflective surfaces of a series of sculpted geometric forms, focuses on Williams and his swimming companions, who had constructed a raft out of detritus gathered from the heavily polluted Lake Michigan (at the time, the boys recalled that the water in their favourite area of the lake would be, by turns, hot and cold depending on whether it was adulterated by effluent discharged by either Keeley Brewing or Consumers Ice Company) and used it to paddle and swim in a zone between the then segregated Black and white beaches, which is where the stoning took place. For Dyson the creation of the raft is an act of resistance, of ingenuity, of architecture both linked and opposed to the space that held enslaved Black bodies as they crossed the Middle Passage. A space that Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, in ‘Fantasy in the Hold’, a chapter included in The Undercommons (2013), describe as one that generated ‘certain abilities – to connect, to translate, to adapt, to travel’ – among its inhabitants, but more importantly ‘a way of feeling through others, a feel for feeling others feeling you’. Which might, in turn, describe Dyson’s London project. It’s notable, indeed, that when she describes the work, Dyson deploys words of a sensory nature: ‘intimacy’, ‘touch’, ‘movement’, ‘proximity’, ‘encounters’. Inescapably, after all that, the sculptural forms in the London show echo the curve of a ship’s hull, and those triangular voids another kind of hold and a play on nautical scale as well as architecture. They offer a potential hiding or conspiring space.

We begin to think of water as space of resistance, liberation, terror, conflict, oppression, refuge, extraction and pollution. In London, the River Thames, the locus of much of Dyson’s research for her show at Pace, carries its own histories of colonisation, community, commerce, trade, transport and the dumping ground of urban effluent. We might think about how we locate ourselves within all that. There is an element of nomadism in the story of the boys’ construction of the raft in Michigan, which Dyson would refer to as an act of architecture. An attempt to exploit a liquid geography in order to construct a free space: to connect, to translate, to adapt, to travel. Aspects of this were foundational to Dyson’s Studio South Zero (SSZ), a (definitively land-based) smallscale, solar-powered wooden studio-structure comprising half of a Quonset hut that the artist was invited to construct by Theaster Gates (supported by his Rebuild Foundation) in 2010. It’s at once a studio for solitary work and, following Dyson’s invitation to other artists (such as sound artist Duriel E. Harris) to use the space, a communal meeting place. A second iteration on wheels, built from recycled materials and conceived as an interactive space, was constructed in 2016 as part of the project In Conditions of Fresh Water. With it the artist and lawyer and social scientist Danielle Purifoy travelled from North Carolina to Alabama, documenting the experience of Black communities and the infrastructures and architectures they, as the pair described it, had to ‘navigate, negotiate and transform’ (the provision of clean drinking water and the biases and injustices inherent in its supply being one of them). It was, Dyson and Purifoy have written, ‘a black-within-black place, a living room where people gathered, lent a hand, asked questions, and offered their memories of everyday life and change in these communities, covering at least seven decades’.

A key part of Dyson’s work then is creating this kind of commons, whether it exists within a community or within the less obviously porous space of a gallery. It’s at once the creation of a space and the liberation from a defined place, through the tracing of the movements of Black and brown bodies in the world. A trace of the waters we hold and the waters we absorb, what we do and what is done to us. To liquidise a space, and to assert that what is fluid can be a place; to feel with and through others.

Liquid a Place is on view at Pace London, 8 October – 6 November, with a performance programme running on 7, 9 and 11 October