Filipino-American artist Carlos Villa – the subject of a retrospective at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco – accessed his diasporic identity through the intercultural solidarity between minority groups

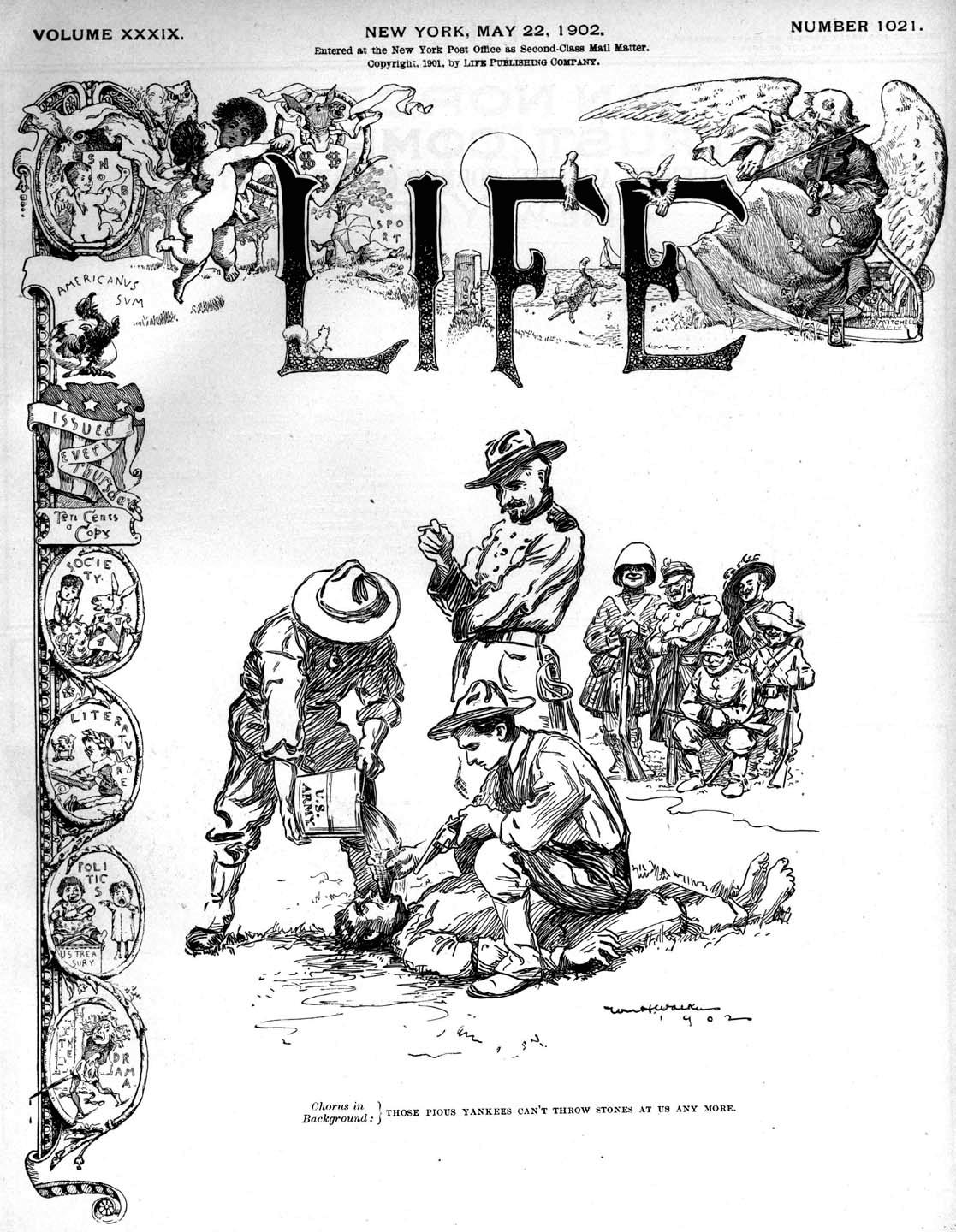

Currently on show at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, having toured from the Newark Museum of Art, where it was on view at the beginning of this year, Worlds in Collision is an overdue first retrospective of work by Filipino-American artist Carlos Villa. It arrives at what feels like a critical juncture of American cultural history, in which American culture’s marginalised voices are now being recognised by its major institutions. That voices from the Filipino-American community, following centuries of invisibility and contempt, are among them (for now at least) is particularly apt; it’s often forgotten that Rudyard Kipling’s famous phrase ‘the white man’s burden’ was first applied to Filipinos (over whom the poet suggested the US should take colonial control) in an 1899 poem about the Philippine–American War. In it, Filipino people are referred to as ‘new-caught sullen peoples,/Half devil and half child’.

Born and raised in San Francisco, Villa studied and later taught at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI, co-organiser of the Asian Art Museum exhibition, for over four decades starting in 1969). Among those he educated were contemporary Filipino-American artists Paul Pfeiffer and Michelle Lopez, and it’s consequently no surprise that the Asian Art Museum show is accompanied by a concurrent second display at SFAI itself.

All that said, Villa spent much of the 1960s in New York, adopting the popular minimalist aesthetic before returning to the Bay Area in 1969 to pursue more ‘authentic’ forms of self-expression: “Not to do a Filipino art but to do an art of my own,” he explained to Paul Karlstrom in 1995, during a recording for the Archives of American Art’s oral history programme. “To do a visual kind of excavation of things to bring me closer to my own root – whatever that root was, being Filipino-American.” And here, perhaps, lies the rub for Villa in particular, but also for those more generally trying to configure a diasporic identity: with little in the way of a precedent for Filipino-American art history – and indeed a ‘lack’ of access to Filipino art history (‘there is none’, Villa was famously told by San Francisco-based abstract-expressionist painter Walt Kuhlman, when he asked his senior how to research it), Villa was forced to articulate his own sense of diasporic identity by looking to other underrepresented cultures around him.

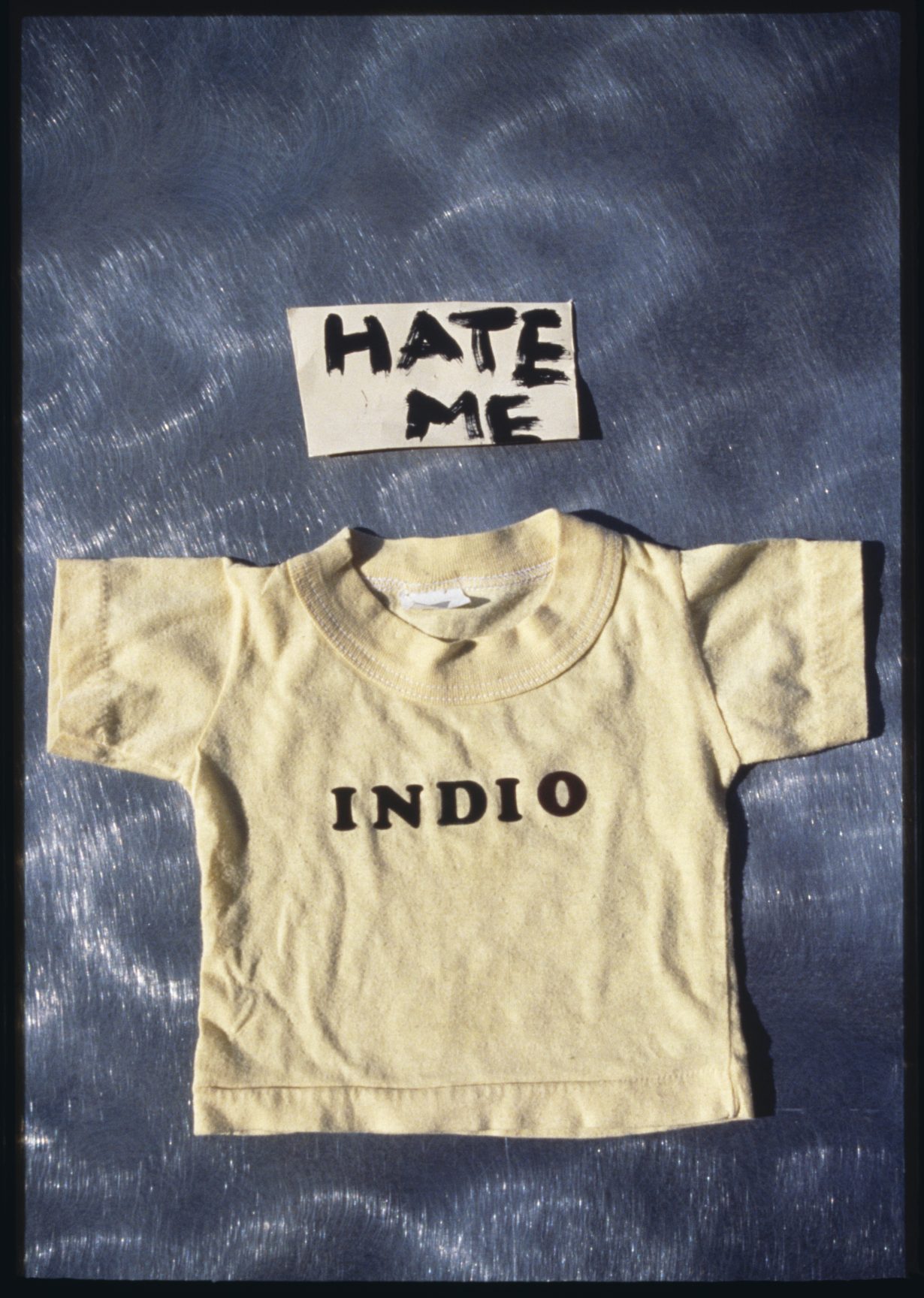

His elaborate overcoat garments, like Second Coat (1977), for example, were inspired by Native American ceremonial robes as well as Congolese nkisi figures. On the coat’s inside, he incorporated his own fingernails, saliva, blood and semen, further (and literally) immersing himself into the various indigenous traditions to which he looked for inspiration. His multimedia works adopted influences from native traditions around the globe because “in using [materials] from those kind of traditions,” he explains, “… [I was] extending what I knew of modernism to what I just discovered about these cultures… To bring about an answer or a way that I could become Filipino American.” Perhaps Villa felt a further kinship to these indigenous cultures, knowing that the Spanish colonisers of the Philippines called native Filipinos indios, just as they had done to indigenous peoples of the Americas.

The exhibition’s catalogue, however, labours to justify Villa’s modernist tendency towards incorporating other cultures into his work: art historian Lucy Lippard assures us that ‘Villa never appropriated, but he invented and paid homage’. Yet Villa’s quest to manoeuvre his Filipino-American identity in the later twentieth century must have been informed by the comradery he found between minority groups in the US, as demonstrated in the formation of Northern California’s social movements. Most important to Villa’s understanding of identity was the Third World Liberation Front of San Francisco State University and University of California, Berkeley – coalitions of Black, Latin American and Asian American student groups.

In the twenty-first century, however, the language used to articulate identity has evolved and become more complicated. In the last decade or so the term ‘Filipinx’ has entered discussions among the US diaspora as a gender-neutral alternative to ‘Filipino’ or ‘Filipina’, and as such is largely used by younger millennial and Gen Z generations; many in the Philippines and among the Filipino diaspora are reluctant to accept the term, however. They argue that ‘Filipino’ is inherently gender-neutral, that the letter ‘x’ is not present within the Philippine alphabet and that, for some, the ‘x’ suffix is another form of ideological imperialism. (Precolonial Tagalog, which forms the basis of Filipino, is largely gender-neutral; for example, the pronoun siya indicates he/she/they, while the precolonial people acknowledged five genders.)

In a 2019 conversation titled ‘Passing as Americans: Filipinx Perspectives on Contemporary Art’, artists Lopez, Pfeiffer and Josh Kline, alongside curators Alex Klein and Joselina Cruz, discussed how contemporary Filipino-American artists navigate their diasporic identity. While it is rare for any of the three artists to overtly implicate their Filipino heritage in their artworks, they all tackle nationhood, imbalances of power and the lure of spectacle. Lopez is an interdisciplinary sculptor known for minimalist industrial installations such as Ballast & Barricades (first shown in 2019 at ICA Philadelphia), in which interweaving multimedia structures made of metal dangle from nine-metre walls, and formally evoke bamboo. In an accompanying catalogue, writer Aruna D’Souza describes how in its ‘importation of the language of bamboo… Ballast & Barricades forces us to recognize the similarities, and therefore the possibilities for solidarity, that tie the poorest American workers to those in other parts of the world’. Kline’s dystopic multimedia and moving-image practice criticises the annals of capitalism and its attendant effects, from nationalism to the climate crisis. He premiered his 16mm sci-fi film Adaptation (2019–22) at LAXART earlier this year, which warns of the catastrophic effects of ‘irresponsible politics and economics’, particularly those pertaining to the Global North. Lastly, Pfeiffer is perhaps best known for his eerie explorations of spectacle and mythologies, particularly in sport; Three Figures in a Room (2015–18) is a 48-minute multimedia installation of Manny Pacquiao and Floyd Mayweather’s 2015 fight, in which the latter was victorious. Pfeiffer isolates certain noises like the thumping of boxing gloves on flesh from the roar of the audience, magnifying the irony of sport’s simplicity against its commercial pageantry.

The 2019 conversation between these three artists (edited and published in the catalogue for Lopez’s Philadelphia show) centred on the notion of ‘passing’; Pfeiffer and Kline’s Euro-American names allow them to traverse the artworld without a multicultural signifier, but Lopez and Villa witnessed what the former called ‘unconscious discrimination’. She expounds: ‘the cultural branding of a name gets into people’s psyche and it’s more powerful than we think’. That said, in making work that does not obviously reference their heritage, the notion of ‘passing’ may also apply to Kline, Pfeiffer and even Lopez’s artistic practices. They recognise the double-edged sword that comes with being an artist with a multicultural background, against which they (and their work) can be susceptible to either being whitewashed or, in Lopez’s words, ‘fetishized through this Western lens of what Asian identity means’.

But while recognising their ability, in varying degrees, to ‘pass’, these artists also acknowledge in the 2019 conversation that the very notion of passing is rooted in ‘otherness’ – as Pfeiffer said, ‘[Passing is] experienced in the form of internalised self-hatred… If there’s any self-awareness of passing, that means you already understand yourself to be different, even fake… To speak of passing at all implies a process of internalised violence and oppression that becomes an indelible part of your internal makeup, your very way of thinking and being.’ Villa similarly experienced this self-loathing as a violent internalisation of the historic white, anti-Filipino sentiment: in Hate Me (1994), Villa photographed a T-shirt embroidered with the word ‘Indio’ just below a hand-painted card that read ‘Hate me’.

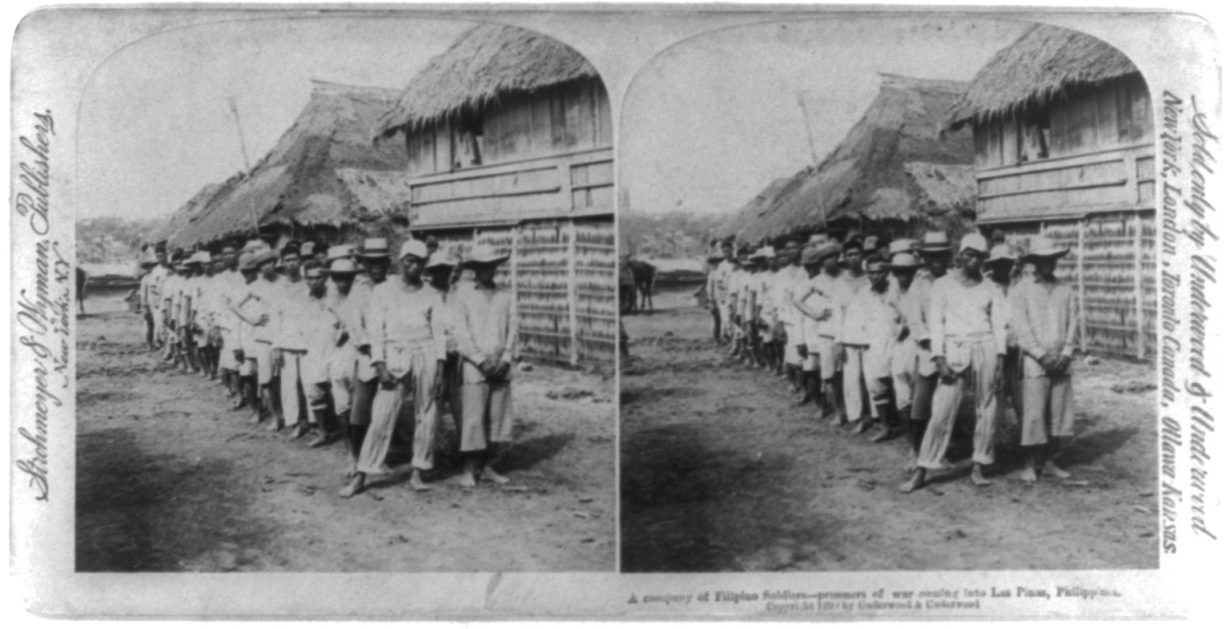

The US colonised the Philippines in 1898, precipitating a period of mass immigration of Filipinos to the US; following which anti-Filipino sentiment turned increasingly violent, including, during the Great Depression, male immigrants being accused of taking jobs and women from white men. During the Second World War Filipinos were legally considered American citizens as part of the us Commonwealth, and agreed to fight for America against Japan for benefits such as permanent citizenship and financial rewards. These were revoked with the Recession Act of 1946. Today, Filipino Americans are experiencing violence as an Asian ethnicity, with a 223.7 percent rise in anti-Asian hate crimes in metropolitan areas, according to the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino.

Despite this anti-Asian sentiment, ethnic minority groups are increasingly recognised in public spaces. With this, however, also comes the artworld and market’s commodification of identity – the exercise of identifying and utilising how cultural difference can be used commercially. Indeed, Villa’s exhibition has been touted as the ‘first major museum show of a Filipino American artist’ in blatantly inaccurate, flashy marketing – Pfeiffer, Kline and Lopez, not to mention many others, have staged significant solo exhibitions at major American institutions. In their discussion, curator Klein points out the corporate interests are antithetical to the very progressive and inclusive politics being instrumentalised: that inclusivity has resulted in a financially lucrative focus. Pfeiffer surmises that ‘identity is thought of in a very specific way in the us as having a currency… [identity politics] is really about a kind of economic structure that’s not about cultural difference at all’. Still, the cognisance of these structures returns agency to the artists who can remain critical of the institution and their own participation within it.

Villa, as one of the most recognisable Filipino-American artists of the twentieth century, accessed his diasporic identity through the intercultural solidarity between minority groups, using an exploratory approach that one might argue has widened the ideological discourse for these three younger artists. Kline, Lopez and Pfeiffer, for their part, have never shied away from their heritage but embrace its complexities within their lives and recognise the hierarchies of power latent within identity politics. As Kline tells me over email, “While our backgrounds absolutely informed the work we were making, it was not the subject or focus of our work. We all were asserting the same privilege as the white artists around us – to make work about whatever we were most interested in, regardless of whether it had anything to do with the countries from which our families had immigrated.” And now a younger generation are attempting to visually decipher and authentically articulate their own distinctly Filipinx experience through symbols of their third culture upbringing. Take, for example, Mikey Yates’s Christmas in California (Auntie Nen’s Apartment) (2021), in which he foregrounds a bottle of Filipino banana ketchup called Jufran. These gestures of introducing cultural signifiers specific to the Filipinx experience do not deny Kline’s statement, rather they synthesise the preceding attitudes with a contemporary consciousness that recognises a visible Filipinx culture in America. Perceptions and the ways in which identity is accessed evolves alongside cultural or historical developments; only time will tell what the next wave of Filipinx-American artists might make from their experiences of diasporic hybridity.

Carlos Villa: Worlds in Collision is on view at the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, through 24 October; a concurrent exhibition will open

at the San Francisco Art Institute on 21 September