On the politics of the facemask and the faces underneath

Viruses do not infect for political gain, or to produce economic instability – they infect in order to reproduce, regardless of who their hosts are. This was understood even during the fifteenth century, when Chinese doctors first developed variolation (administered nasally via insufflation) as a way to accomplish immunisation against smallpox, caused by the variola virus. And yet, to many people today, COVID-19 is ‘accidentally on purpose’, and its hosts are ambiguously ‘East Asian’. Aside from placing Chinese people in the firing line of xenophobia and global division, this perspective tends to hide the fact that were COVID-19 not simply a ‘Wuhan virus’, it might present an opportunity to rethink the systems of global ecological destruction, our planetary illness (ours, at least, in the sense that we caused it), which has been mutating asymptomatically since the early nineteenth century, if not earlier (perhaps since Columbus set sail, but going back, in any case, long before ‘where is Wuhan?’ Google searches peaked). If COVID-19 really has communalised us, then presumably we will all have ‘Asian immunity’ soon.

But in the twenty-first century, political and economic systems do not ‘remove’ people and bodies in the ways they once did. How this pathogen will affect parts of society that were already in ‘crisis’ is unclear. There are no neon signs, just dismay to the brain and a foreclosure of the heart.

January

In early January, living in Beijing, we started to receive hints of an invisible tsunami that was about to hit. Full force. Chat groups began to stutter raw concerns; I’d never seen someone cry on WeChat before. Meanwhile, I found myself lost in the beauty of the passing winter, in the hutongs. In 2020, January really is the cruellest month.

This was before the term ‘COVID-19’ was coined, before any deaths had been officially reported in China, and all we had were the yao yan, ‘informal news’ reports, from which to piece things together. It was like using a fan outdoors on a windy day. Clues stayed in the ether for only a few hours, choked off by an expanding algorithmic grip. (How greatly the West misunderstands the potential of clicktivism.)

In the period just before the Lunar New Year, information became clearer: images and facts started to grow from between the cracks in Hubei province’s capital city (the city remembered for kindling the 1911 uprising that overthrew China’s last imperial dynasty). Nevertheless, the fragmentary WeChat posts, and the gong zhong haos that publish them online, left yawning timeline gaps. An exquisite corpse of information for us to play.

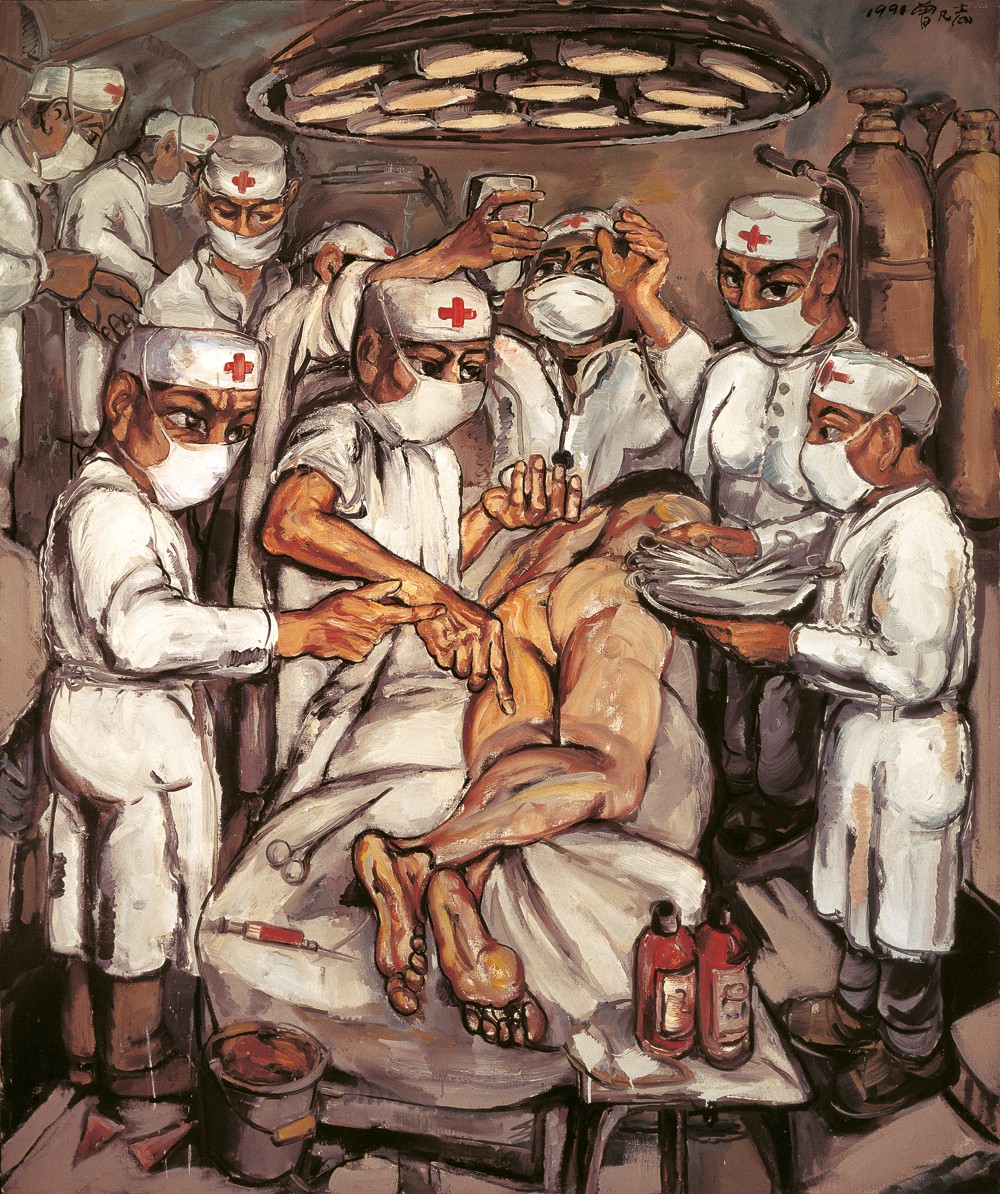

Despite this, or because of it, I witnessed a community rising up: colleagues and strangers coming together to support those on the frontlines, the original avant-garde. From museums to art fairs, we tried to find forms of solidarity and generosity as a temporary vaccine – a song we could all sing.

The first ‘quarantine’ gave us time to react – or not. And the heroes will never be known, not publicly. I’m reminded of On Kawara’s ‘Date Paintings’, not the ones we know of, but the ones he had to destroy because he couldn’t finish them by midnight. The result of his self-imposed strictures.

On 10 January, when Chinese scientists first sequenced the genome of the virus for the world to access, its mutation into a new form of bio-racism – which truly occurred when the virus appeared in Euro-America – was unimaginable to them. They were dealing with a new genetic identity that didn’t need a visa, skips the queue at the airport after a 12-hour flight and, when caught, nevertheless passes through. A new biopolitical ‘language’ emerged malignantly from the lips of mainstream media – one that would help create a rise in COVID-19 denialism. But what we needed was a new language to help navigate our heightened simulated reality – a new isolated interface – one that is being sustained by mobile applications and online location-based services.

Meanwhile, in China, at M Woods, we closed our doors and began to think about how social-media platforms might become a site upon which culture could reconnect, where artists might gather during the quarantine period. Given that art is now a battle against inarticulacy.

February

In London (and probably most places outside of East Asia), when I arrived there to reorient museum programming, things were different… it was business as usual: European and American news focused far more on the details of people’s diet in Wuhan and the geographical origins of the disease than the preemptive measures put in place there, which in hindsight should have been considered globally at the same time. The diminishing of scientific voices may not be culturally specific. Inexplicably, here COVID-19 wasn’t happening – or rather it was, but only among the Chinese and their diasporas, or more crudely, within urban areas branded ‘Chinatown’. Inevitably, as an immigrant, I never fear this ‘home away from home’ and visit anyway.

London’s roads were characteristically tossed and wet, the wind still full of someone’s Tesco bag – a pleasant embrace. Institutions and businesses remained open, and Asian international students were not much more than an unwelcome speed bump placed in a bourgeois neighbourhood. It is as if your neighbour has suddenly woken up imprisoned in the 36 chambers of ‘yellow peril’ – not ‘Wu-tang’, but ‘Wudang’.

At a friend’s opening, I was asked by a group of strangers if they could take a photo of my friends and me (we were all wearing masks and gloves). We declined, and this prompted a variety of responses (I wouldn’t know about them all – I stopped listening). It was like a scene from Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962): no one believes that we have come from the future, and that soon there will be no more toilet paper (a sixth-century Chinese invention, if you want to play that game, which would be ‘invented’ in the ‘West’ only during the nineteenth century).

I reminded my European friends that kissing is forbidden, and that soon political maps would be redrawn. It’s fine, an ‘informed’ friend told me, our government’s top scientists have recommended washing hands. The online university of Facebook has started to give out degrees in virology: now everyone is an ‘expert’. A sense of relief fills the circle. I visualise the speed of misinformation moving like an ‘asymptomatic’ sneeze through an overcrowded District Line train as I leave, dolefully.

Inexplicable, to me then, was how we were both ‘virus’ and living – not alternately but simultaneously. The US Surgeon General tweeted that masks ‘are NOT effective in preventing the general public from catching #Coronavirus’. This made me feel, strongly. Imagine if indigenous peoples had had test kits during colonial expansion. Living on the Musqueam (xʷməθkʷəy̓əm) Indian Reserve as a teenager, I learned that European ‘contact’ and novel diseases defined the genetic make up of sovereignty and ‘reconciliation’ for First Nations peoples occupying unceded territory.

Since then, wearing a facemask has become a dividing issue in global-health information and governance. Power and violence are exercised at a distance, and the mask has become an identifiable antagonism, within the psyche, for the ‘West’, threatening its inhabitants’ rights of ‘freedom’ (like using chopsticks to eat chips – nothing is safe). As a result, mandatory health policies in East Asia have taken on a biopolitical dimension for East Asians and their diasporas.

For most of the already marginalised, quarantine is not an option – finding a bed is hard enough.

To be clear, the disease hasn’t just left its mark on Chinese culture. It has become the very device it was designated to be by Euro-America, marking even those who are not ill, and have never been to China: diasporas. No exceptions for those abroad. Even Southeast Asians now? For some, not looking the ‘same’ has become a survival project. But there is no dodging this draft. (Remember when ‘Asians’ were OK a few diseases ago? When Crazy Rich Asians rewrote the narrative for the general public?) But who’s free from this, anyway? The centuries-old disjointed status that diasporas have enjoyed as ‘semidetached’ observers in North America and Europe couldn’t have been reversed faster.

We have a name now – ‘COVID-19’ – and soon, I suspect, the shared ‘naked life’ will come for those who already had no way out. Where ‘normal’ never existed, but ‘diversity programmes’ made you feel that it might. The Chinese have no monopoly on being victims of xenophobia. (The target is not only ‘us’.) Especially the parts of society that the colonial and neoliberal immune system deems to be a virus. Europe and the United States haven’t introduced forced lockdowns yet – I guess the economy really is ‘special’, right? In a recent Skype with artist Tehching Hsieh, we spoke about the one-year performances he began while living in New York as an illegal immigrant from the 1970s onwards. I wonder how performances such as his Time Clock Piece (One Year Performance 1980–1981), which involved punching a time clock every hour for a year, might offer more insight into our current ‘quarantine time’ versus our ‘postquarantine time’. Hsieh reminds me that we are all isolated but united together through time, and that freedom of movement, for many, is already conditional. I hope this long exposure to solitude doesn’t desensitise us, and the politics of the facemask in the West become an obscure footnote to the common condition of community care that connects our shared cultural experiences in our interdependent, crumbling world.

Victor Wang is artistic director and chief curator of M Woods museum in Beijing