Are states and philanthropists truly interested in paying artists for ‘doing what they love’? Or does the proliferation of quasi-UBI programmes point to a future of increased control over who gets to be an artist?

The pandemic has had many detrimental effects on the arts, but recently the Western artworld has developed a peculiar form of ‘long COVID’, whose key symptom is the demand for a special form of income for artists, with a plethora of initiatives cropping up that single out artists as uniquely deserving of support in the post-pandemic reconstruction. In 2021, for example, the New York City Artists Corps promised to employ artists in droves to restore the creative and tourist economies. Ireland is poised to launch a €25 million guaranteed income (GI) pilot for artists. And numerous programmes, such as Creatives Rebuild New York (CRNY), are currently trialling versions of universal basic income (UBI) targeted at artists. For the 2,400 creatives selected by CRNY, who are now a cool $1,000 a month closer to making rent, such initiatives may be a blessing. But are states and philanthropists truly interested in paying artists for ‘doing what they love’? Or does this proliferation of quasi-UBI programmes point to a future of even lower artist incomes and increased control over who gets to be an artist?

Blueprints for Universal Basic Income date as far back as Thomas More’s Utopia (1516). The aims of the spate of recent trials of UBI in countries ranging from Namibia to South Korea have included reducing child malnutrition and promoting local businesses, while a programme launched this spring in Wales is directed at young people leaving social care. Figures as far apart on the political spectrum as Britain’s former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn and Tesla’s Elon Musk have advocated much wider applications of UBI that would see living-wage-level payments distributed to entire populations.

For all its appeal, UBI is a neoliberal con designed to disenfranchise vast parts of society and undermine the earning power of all but the capital-owning elites. In a world where human labour is rendered obsolete to the extent that a significant portion of the workforce would be paid to stay idle, the human itself will become surplus to requirement. This is not because work is intrinsically necessary to human dignity but because when the worker has been stripped of their ability to produce, it won’t be long before they are also deprived of the means of democratic participation. We are already seeing the beginnings of this process: American commentator Joel Kotkin observes the millennial generation’s lack of interest in the world of work or political participation. Add to this the so-called ‘great resignation’ (the phenomenon of rising rates of workers quitting their jobs in recent years) and a future where, in Kotkin’s words, a ‘managerial elite delivers food, housing, and pleasure to unemployed and demotivated plebs’ is on the horizon. Despite this, polling in Britain suggests that more than half of the UK public support the introduction of UBI, a figure only set to rise as the population is battered by yet another cost-of-living crisis.

But a guaranteed income for artists is neither universal nor basic. Some of the over 30 trials currently underway in the US – whose collective price tag is, according to the Financial Times, $150m – are committed to selecting recipients at random in the vein of earlier experiments. Others, however, expect artists to contribute to communities in return for payments. A scheme in Minnesota perversely asks artists to make work that ‘demonstrates the need for guaranteed income’, as though to prove that a person forced to labour for the $500 a month this scheme provides will remain dependent on handouts forever. A trial run by the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (YBCA), in San Francisco, makes a virtue of its ideological bias and boasts of ‘randomly’ allocating 95 percent of payments to individuals from marginalised groups.

In many ways these schemes are no different to traditional grants, fellowships or residency programmes, which continue to abound. And like the earlier formats, these guaranteed-income projects have their political motivations. Ireland’s artist GI pilot ostensibly aims to resurrect the country’s minuscule visual art scene while dispensing with the Irish government’s manifesto commitment to trial UBI. YBCA pays race reparations despite such positive discrimination likely being illegal when public funds are involved. Others are straightforward, if modest, investments in socially ameliorative art practices accompanied by stricter-than-ever evaluation criteria. What’s new is the all-encompassing nature of these schemes. Whereas previously anyone could have been an artist in Ireland so long as they were happy to declare themselves as such on the census, the Irish state has now decided that it ‘needs’ no more than 10,000 artists. CRNY turned away some 19,000 applicants.

What will the excess artists do? Here lies the artworld’s biggest taboo: how many artists are ‘enough’ and who gets to decide? Past decades have seen a meteoric rise in the supply of arts graduates, only a fraction of whom have been able to find employment in the creative industries. Despite also rapidly growing, the artworld has become accustomed to an overabundance of available labour, and this has contributed to the suppression of pay for art workers. Campaigns by the likes of the US’s W.A.G.E. highlight that unpaid labour remains commonplace in the artworld. However, hardly anyone entertains the idea that a mural artist would attract a higher honorarium if they didn’t compete with ten others for the same commission, despite the inverse situation currently driving up wages elsewhere, such as in the hospitality sector. Artworld dogma is that there must always be more art and more artists, at whatever consequence and whoever’s cost.

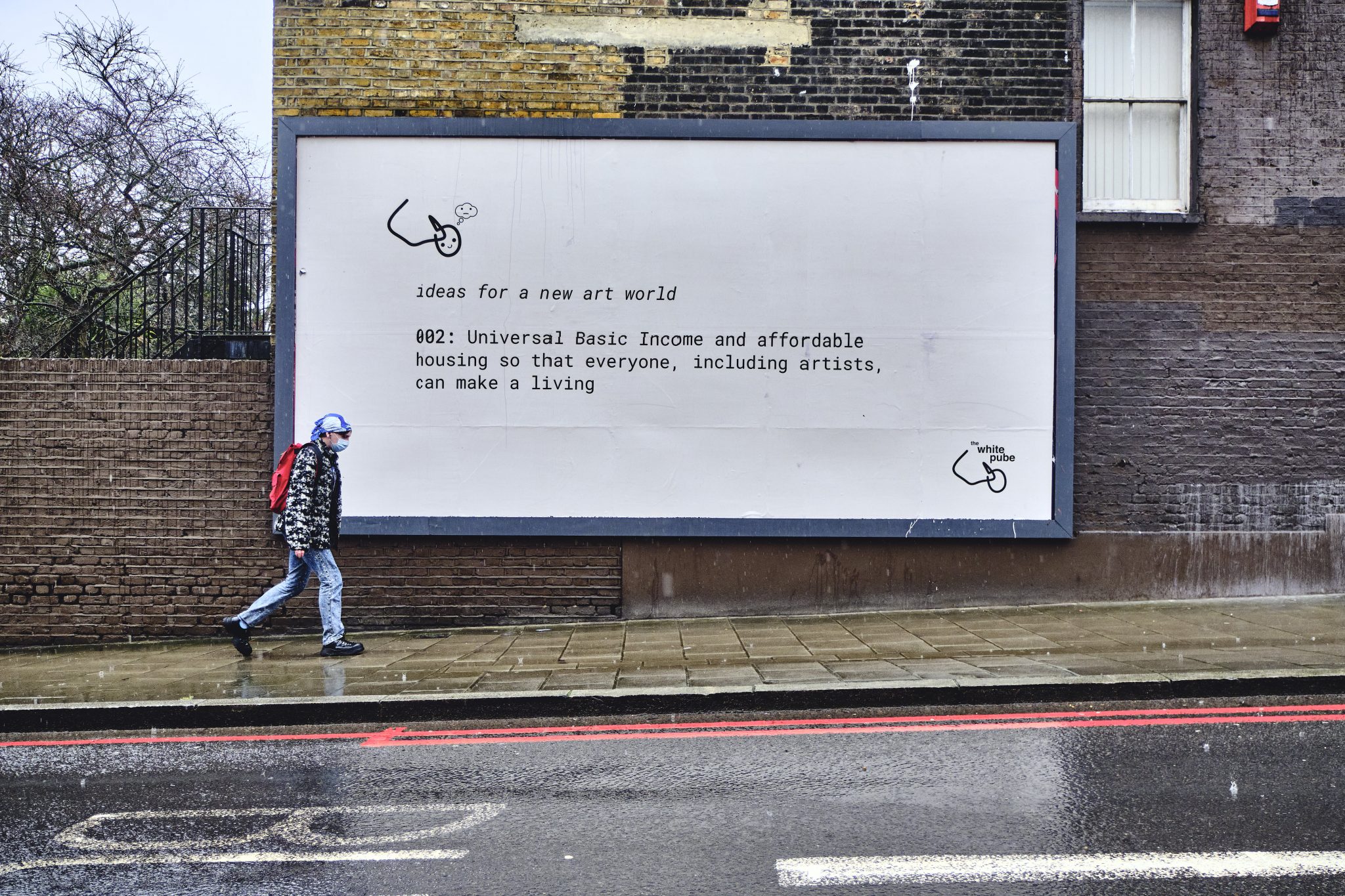

If, as reports consistently show, the artworld is plagued by in-work poverty, is welfare the answer? Artists’ GI makes a mockery of the ‘art work is work’ slogan, whose double-edge confusion was illustrated by art-writer duo The White Pube’s 2021 poster campaign demanding the introduction of UBI ‘so that everyone, including artists, can make a living’. How does anyone make a living on a state handout? Shouldn’t we be rewarding artists for the work they do within the labour market, in which artists are subject to the same supply and demand mechanisms as nurses or lawyers? We already have state and private funders to correct for market failures, but when is enough enough?

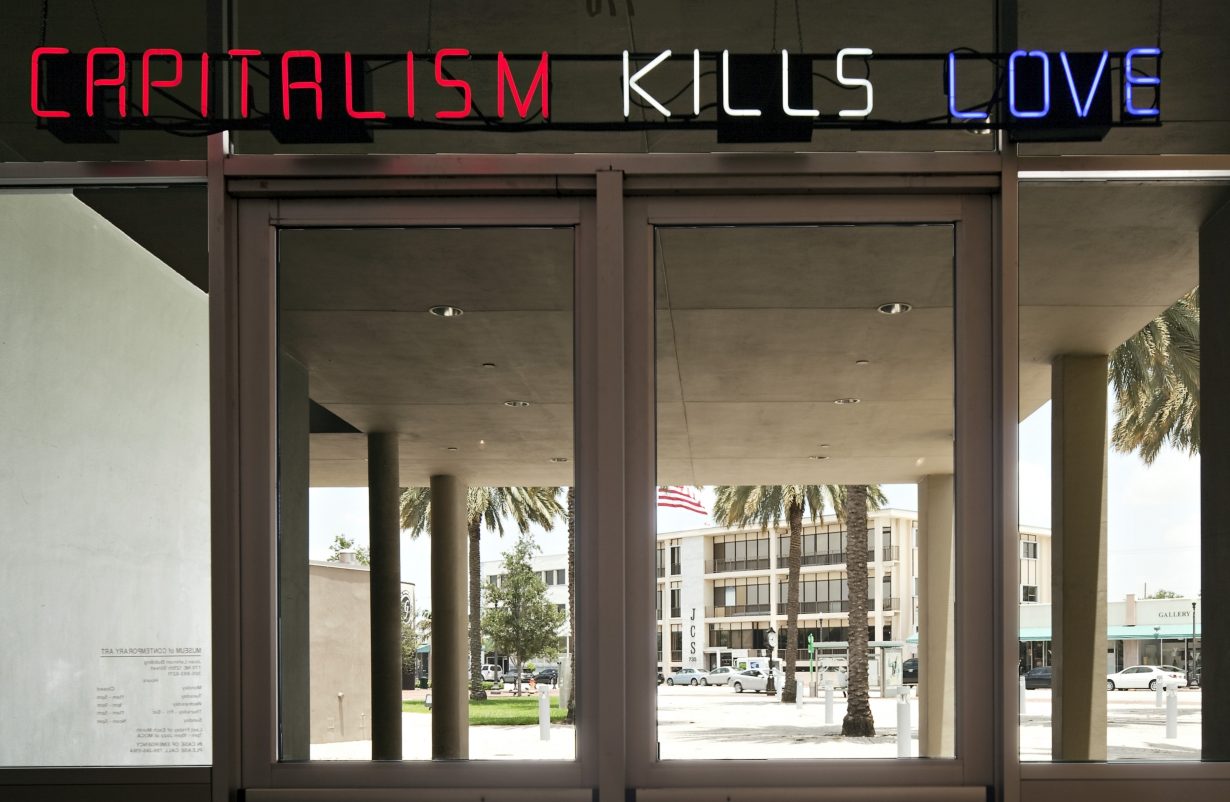

Cue arguments for art’s exceptionalism: YBCA reminds us that artists ‘shoulder the difficult work of making meaning from life in our world today’, while CRNY proposes a ‘too big to fail’ catch-22, claiming that ‘improving the lives of artists is paramount to the vitality of New York State’s collective social and economic wellbeing’. Add to this the self-satisfied praise for the creativity and critical thinking ostensibly unique to artists and one could almost forget that the very same artists serve the capitalist structures of the university, the museum and the auction house they were a moment ago protesting.

That guaranteed income won’t solve the underlying problem is made evident by the art market’s present detachment from the material realities of the majority of artists. The megagallery, paradoxically one of the few spaces in the artworld where high earnings are commonplace, already thrives on the oversupply of talent by simply turning most of it away. With GI, the blue-chip gallery would have the state’s collaboration in the branding of its roster as even more elevated from the grey mass of ‘Universal Basic Artists’, whose work is deemed worthy of only the minimum wage. And it is unlikely that any income guarantee would be significantly higher, because the state suspects that artists perversely enjoy their work and that the occasional declarations of public gratitude, in the form of those poster campaigns that artists are already happy to design for themselves, should be enough.

Not only will the GI artist be limited by the generosity of the public and philanthropic funding institutions, they are also unlikely to see the creative freedoms promised by UBI. As is the case today, the artist will have to choose between trying to climb the art-market ladder or complying with the politics of the institution. Failure to break through the closely watched gates of either will render the artist an outsider, except that there will be little glamour in this, since a multitude of other outsiders will be making the same bid for relevance. This has happened before: the official artworld’s desire for control over independent artistic activity saw the UK’s politically vibrant community-arts movement of the 1980s neutered and co-opted into the trend for publicly funded ‘participatory art’ since the 90s. Documenta’s recent unironic inclusion of a Dutch NGO in its list of artists, the per-head allocation of production budgets and the resulting exhibition’s impotence in the face of political challenges indicate where all this may be going.

What is the case for prioritising art-school graduates for GI when UK hospitals are opening food banks to support their struggling nursing staff? Is it the thinly veiled cartel protectionism that saw Serpentine Galleries artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist register the arts’ claim on the public purse just four days into the UK’s first coronavirus lockdown in March 2020? Is it the erroneous conviction that the arts are the key economic driver of the creative industries that was at the heart of the #artisessential campaign that proposed fast-tracking the arts for investment? Or the ridiculous claim that the art school contributes vitally to the medical industry, as put forward by the vice-chancellor of London’s Royal College of Art?

Between such demagoguery, false consciousness and genuine economic hardship, the arts became the unlikely site for this latest round of basic-income experiments. The inconclusive results of the recent Finnish UBI trial and the failure of US presidential candidate Andrew Yang’s platform in 2020 should have given pause to UBI’s staunchest advocates. When even the socialist journal Jacobin has understood that the short-term effectiveness of pandemic support schemes is no promise of UBI’s glorious future outcomes, we might wonder what makes artists into such compliant guinea pigs. The answer lies, as ever, in art’s exceptionalism: income guarantees will work for me, or for us, but they mustn’t become universal any more than the practice of art itself.