‘Pan-shamanism’, spiritual mediums, hidden histories, deep trauma, time travel – are these the base materials that will reshape contemporary China?

Wang Tuo is an artist interested in the possibility of a democratic revolution in China. His art – which spans film, performance, painting and drawing – meticulously interweaves his understanding of diverse times and spaces with fiction, mythology, archives, memory and instances of political turmoil. Beginning with historical events, such as the anti-imperialist May Fourth Movement of 1919, he recontextualises the modern histories that lie concealed behind China’s cultural censorship and state control.

Earlier this year, in The Second Interrogation, Wang’s first solo exhibition in Hong Kong (at Blindspot Gallery), the artist fed this concept through the loom of Chinese politics. Accompanied by recent paintings and drawings, the titular artwork (a two-part video from 2023) took the form of a fictional dialogue between an artist and a local Commissioner for Discipline Inspection, where Wang explores the role of art and the artist in contemporary China. At one point, the artist character poses the question: “Can art actually bring about change in the real world?”

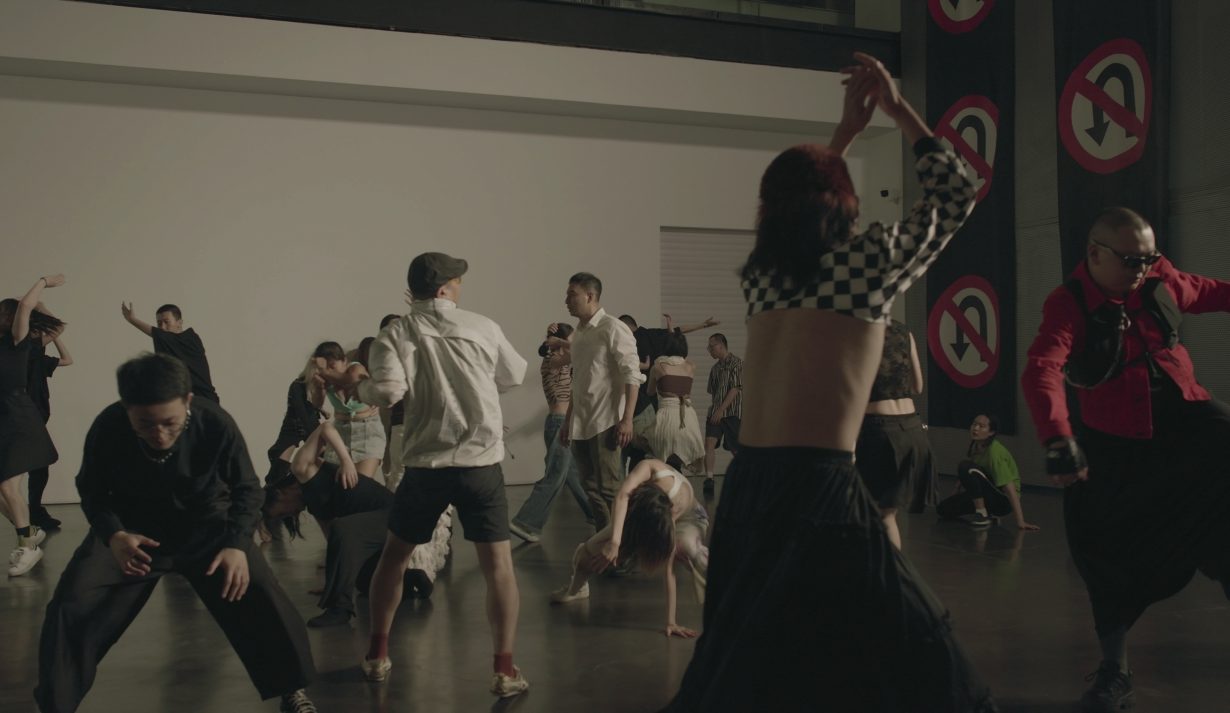

Wang situates his performance within scenarios that are at once scripted and open to interpretation: encouraging the actors to tap into their personal experiences, relationships, traumas and imagination. Wang presents human bodies as spiritual mediums: pseudo-shamans that are trapped in histories doomed to repeat, ritualistically synchronised across time and space, much like China’s attempts at governmental reform and managing censorship. The result of all this is what Wang calls ‘pan-shamanisation’, in which humans are conduits of historical consciousness: the living and the dead coexist to conjure a diachronic narrative that embraces both the passage of time and the events embedded in it.

The radical point of the dialogue in The Second Interrogation lies in the artist’s tribute to the 1989 China / Avant-Garde exhibition at Beijing’s National Art Museum of China (curated by Li Xianting, Peng De and Gao Minglu), a watershed moment in the history of Chinese contemporary art. One of the restrictions placed on the exhibition was that no performance art be included. Those consequently affected by this rule staged a series of seven performances: Datong Dazhang, Zhu Yanguang and Ren Xiaoying’s walked through the exhibition space in white sheets to demonstrate mourning rituals; Wu Shanzhuan set up a makeshift market stall from which he sold 30kg of shrimp to criticise the commodification of art; Wang Lang wandered around the museum dressed as an ancient Chinese warrior and terrorising visitors; Li Shan washed his feet in a plastic bucket to which he had attached a portrait of Ronald Reagan; Zhang Nian sat on a ‘nest’ of chicken eggs wearing a placard around his neck, which bore the pointed message: ‘No theoretical debate during my floating egg performance, lest it troubles the next generation’; Wang Deren threw condoms and coins at visitors as a comment on China’s increasing population; and Xiao Lu fired two bullets at her own installation with a pistol. These performances provoked controversy and, eventually, retaliation from Chinese authorities.

The artist in The Second Interrogation at one point gives a talk recounting these performances; the film itself is narrated by an actor playing the performer Datong Dazhang, who died by suicide on New Year’s Eve 2000. By retelling these moments in relation to 1989’s Tiananmen incident, Wang questions whether there is any value in continuing the task of establishing the freedom of artistic expression that his predecessors failed to achieve over three decades ago. While those ghosts from the past seem almost to roar in the face of their subjugation, in the exhibition a series of unfinished portraits of Wang’s compatriot artist-friends (“Weapons”, as he calls them, during our interview) hung on the wall as if to testify to a possible future – one in which freedom of expression is not a threat. Says the artist: “To decide to live is the original power of the powerless; it is also the weapon of the weak in everyone’s hands.” By juxtaposing the past and the present in this way, Wang articulates the ways in which art scrutinises current sociopolitical conditions through the lens of history and how an artist might weaponise their practice for social resistance.

At another point in The Second Interrogation, the artist fires a gunshot into the air. The gesture acts as a nod to Xiao Lu, who recounts in Wen Pulin’s 1989-2009 documentary, Seven Sins: 7 Performances during 1989 Chinese Avant-Garde Exhibition, the moment she fired two gunshots out of three at a mirror that formed part of her installation Dialogue (a pair of phone booths), after which she was arrested. Wang supplies a glimpse of revolutionary thinking against an authoritarian system in The Second Interrogation, the shot fired into the air by the artist a reincarnation of Xiao Lu’s missing third bullet. A bullet that audiences may or may not interpret as symbolic of the possibility of a gradual revolution in the hands of those who understand what belongs to them and how to own it.

In a dimly lit red-wallpapered room at the Taikang Space in Beijing, two leather armchairs sitting on top of decorative carpets welcomed viewers into the artist’s exhibition A Little Violence of Organized Forgetting (2016). Wang arranged the exhibition like a theatrical set to elaborate on the mythology of family bonds and their traumatic ruptures; the result felt more like standing in a living room of phantoms. There he premiered Meditation on Disappointing Reading (2016), a video based on American writer Pearl S. Buck’s 1969 novel, Three Daughters of Madame Liang, long banned in mainland China for depicting a Chinese family tragedy during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). After discovering the book while studying painting at Boston University, Wang tells me that he found Chinese online databases had all but erased its existence, leading him to consider the connotations of ‘absence’ in the writing of history. In this sense, an archive isn’t a mere system of preservation but one that reflects specific regulations about what can and cannot be said. In other words, an archive is never neutral; it is shaped by the sociopolitical order within which it operates. Thus Wang asks whether or not ‘the archive’ ever enables us to look at official narratives without simultaneously requiring us to ignore the possibilities of an alternate historiography.

In Meditation on Disappointing Reading, Wang intertwines the lives of two women. Onscreen a female character prepares food in a ritual to summon spirits: a ghost appears to tell a tragic story from a third-person perspective, inspired by a chapter of Three Daughters of Madame Liang. As an intertextual way of summoning an absent archive, Wang translates the chapter into Chinese via Google Translate, thus yielding a confused grammar that deliberately obscures the banned source as well as the details of the era during which it was first written. While the translation program’s disjunctured reading leaves the audience disoriented, the gist of Buck’s story remains lucid. Wang presents a deft metaphor for the archive, with an ambiguous connection between a person who is allowed to read the novel and the person who cannot access it, a story retold by ghosts who represent a haunted narrativisation of collective trauma.

A similar kind of “double wounding”, as Wang puts it, of combining disparate moments takes place in his video Tungus (2021). Filmed in Wang’s hometown of Changchun, in Jilin province, which is geographically adjacent to North Korea, Mongolia and north-eastern Asia, the video raises questions of ethnocentric nationalism, border crossing and diaspora. Threading together narratives of two soldiers and a scholar attempting to escape from the tangles of the Chinese Civil War (1945–49), the film nods to the contemporaneous Jeju Uprising (a precursor to the Korean War) and the 1919 May Fourth Movement, and also incorporates still images of illustrations of The Peach Blossom Spring (fifth-century author Tao Yuanming’s mythological story of a utopia in which inhabitants have escaped the civil unrest of the Qin dynasty to live oblivious to reality). Blurring time and space, the historical landscapes of Changchun and Jeju Island become a backdrop of collective memory that reveals the commonalities between the civil wars. By interweaving human narratives with the political circumstances of northeastern Asia, Wang uses pan-shamanisation to uncover the ways in which collective memory has been reshaped by ideological hegemonies that seek to revoke historical trauma.

The archive – as a system for storing knowledge – is subject to constant mutation, adaptation and manipulation in which cultural memory isn’t guaranteed to be kept intact from past to present, from generation to generation. Wang presents his audience with the possibilities of writing different historical endings that challenge those dictated by authoritarian systems. And in giving space to those underrepresented human stories, Wang demonstrates how one can deploy what anthropologist James C. Scott describes as the ‘weapons of the weak’.

Wang Tuo is shortlisted for the Sigg Prize 2023