The preexisting parameters for recognising ‘contemporary art’ as opposed to the ‘decorative’ show the unlearning still ahead of us

Colonialism is not a thing of the past, but has enduring afterlives. In Oman, which was once subject to Portuguese then later British imperial influence, some of these persist because the legacies of colonialism continue to structure our unequal world more broadly. British imperialism during the early to mid-twentieth century had a globally lasting effect on art and culture. A ‘denial of coevalness’, as cultural anthropologist Johannes Fabian described it in 1983, undergirded Britain’s self-appointed ‘burden’ of ‘bringing culture’ to its darker-hued subjects. Fabian identified how imperialism benefited from the erroneous claim that geographic distance from the West equals a regression in time. It served as a means of teaching people, both at home and abroad in African, Arab and Asian colonies and protectorates, what did and did not constitute ‘the present’; where ‘civilisation’ dwelt; and towards whose aesthetic tastes peoples of the Global South apparently, belatedly, marched.

The parameters for recognising what is contemporary art are still largely determined by wellresourced Western contemporary art institutions like New York’s MoMA, Paris’s Pompidou or London’s Tate museums, and in turn inform the major auction houses, biennials, university courses and art awards. Anish Kapoor’s Vantablack works (2016–), Damien Hirst’s formaldehyde animal works (1991–2017), Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds (2010), Marina Abramović’s performances (1973–), Ayşe Erkmen’s site-specific Kıpraşım Ripple (2017): these global artists and their diverse practices pose examples of works that have been recognised by major Western art institutions and curricula as, indisputably, ‘contemporary art’. I do not propose these artists perpetuate an imperialist understanding of art (Ai Weiwei’s Lisson Gallery show was cancelled in November 2023, for example, for his solidarity with Palestinians), but make an observation about the conceptual, largescale and resource-intensive works they have in common. While what constitutes ‘contemporary art’ can be an ongoing philosophical debate, concepts like the colonial ‘denial of coevalness’ show us that any temporally periodising word, such as ‘contemporary’, contains a spatial assumption within it. The characteristics of works like the above, which are recognised as ‘contemporary art’ in the West, share some similarities: they usually cannot be physically touched, cannot be easily recreated, do not have a practical function, are usually monetised for private ownership, are credited to an individual’s imagination and aim for originality over communal familiarity. Are these universal attributes or values of the ‘now’? These characteristics may not necessarily reflect the aesthetic forms and creative priorities of several visual cultures in the Global South. This is not to say artists should be restricted in terms of inspiration, form and materials to their own roots; it is about freely asking ‘why’, rather than assuming any

system of aesthetic valuation is neutral or ahistorical.

Omanis have not escaped the influence of this value system: the notion that art with decorative or cultural functions is somehow not really ‘contemporary art’, which must apparently be conceptual, largescale and resource intensive, persists here too, speaking to the Sultanate’s complicate imperial/colonial history. There is a distinct sense among many Omanis like Raya Al Maskari (who, like all artists I met, has a day job) that they are still taking ‘baby steps’ because ‘big conceptual artworks are difficult’ in terms of domestic sales and reception. At Oman’s Affordable Art Show, which was in its eighth edition in December 2024, participating artists lamented that local tastes and customs resonate with small decorative prints and objects, rather than largescale conceptual works such as site-specific installations or video art. This begs the question: should artists expect their community to change their aesthetics according to their artists’ tastes? Or, put differently, who does an artist seek to serve with their art? The answer doesn’t necessarily have to be ‘their own community’, but if they believe their local context is somehow not yet at artistic maturity, then it is worth critically examining what influences them to think so, before assuming the society must catch up to the artist. Asking why artists feel the need to measure themselves against parameters that are not those of their own community does not equal circumscribing their artistic freedoms. It is about being constructively critical of potentially underlying assumptions that some people have to play catch-up to tastes that may not be their own but those of the global art discourse du jour.

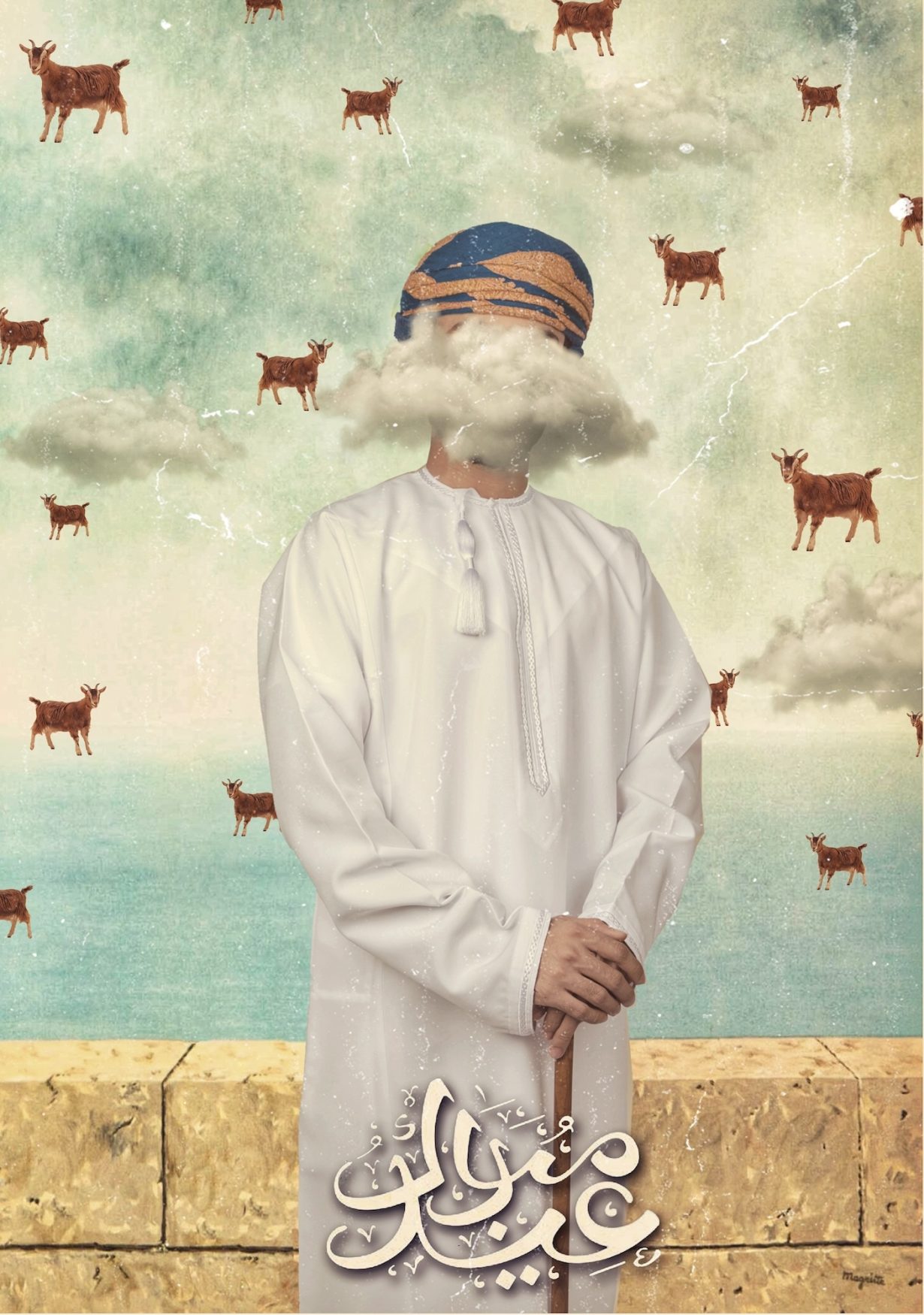

Omani decorative and culturally functional art may not have made much of a dent in that global art-discourse yet, but it is easy to see why it speaks to local tastes and buyers. It often conveys distinct senses of place related to the country’s complex history, often abstracting and playing with these. Its textile arts (especially women’s traditional clothing) feature motifs as diverse as Balochi, Sindhi, Zanzibari, Somali and Yemeni. At the aforementioned Affordable Art Show, works included paintings that reinterpreted Omani architectural shapes, such as the colourful doors found in its mountain villages (Safiya Al Bahlani); decorative sculptures made of found materials like fish bones from the country’s 3,165 kilometres of shoreline (Emerson Sumaoang, who makes works under the moniker Mhearts); and irreverent collages incorporating historic objects like the khanjar (dagger) alongside the kitsch symbol of a local 1990s childhood: a Chips Oman packet. None of these are largescale or site-specific installations, but they are evidently contemporary to the local context, where purchases of small works usually occur to support a favourite artist one knows personally, and

private collecting for home display is not an established practice because the domestic sphere is barred to nonrelatives. Evidence of what photographer Ahmed Abdullah Al Busaidi’s told me is all around: “After all, our grandfathers and grandmothers are artists, in their making of clothing and handicrafts, in storytelling.” But he too bookends this assertion, with the disclaimer that theirs is an art scene in its infancy. A system of valuation that assumes certain characteristics of contemporary art can make it difficult to shake the notion that certain places must eventually ‘catch up’ to others’ visual cultures.

assemblage. Courtesy the artist

It would not be hard for Oman to mimic the kind of works venerated in the Western biennale and auction house, if it so wishes. It has money and a tiny population, almost half of whom are under-18s; education in Western Art History can be rolled out, bursaries and materials provided. But is that something to be wished for? The Raneen art festival that ran in November 2024, which used its space across restored traditional houses (a combination of mud and carved-wood doors) in the country’s old commerce hub of Muttrah to exhibit site-specific installations, serves as an example. Its centrepiece, a giant moon in a courtyard – a touring work by British artist Luke Jerram that has been presented more than 300 times in more than 30 countries – was striking, but seemed more of a cool photo op for a day out with the family than anything particularly related to what Omanis are making and buying. There is no need to aim for more of the same when it neither promises local artists a full-time livelihood, nor a connection to the everyday historic sources of their inspiration.

That art with decorative or cultural functions is somehow considered ‘baby steps’ taken towards full-blown ‘contemporary art’ rests on assumptions that we find, among other things, in notions inherited from colonialism – like what is and is not of the ‘now’. It evidently still influences psyches, artistic practices and cultural economies around the world. The Western contemporary art world is free to judge non Western contemporary art as it wishes; the bigger problem occurs when its parameters are, consciously or unconsciously, internalised and reproduced by artists, curators and culture ministers in the Global South. Opportunities to revive and reinterpret local visual cultures and build upon a living aesthetic heritage are missed, and a promised land of contemporary art that is neither relevant nor indigenous to regional audiences is sought. Oman, with its emerging art market still reliant on local sales and tastes, may have a unique window of opportunity. How might its art community attempt to step outside of the Western contemporary art paradigm?

Sarah Jilani is a lecturer in postcolonial literatures and world film at City, University of London

From the Spring 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.