From ‘NGO aesthetics’ and OKish painting to the increasingly blurred lines between culture and high-end lifestyle: 2022 in the artworld

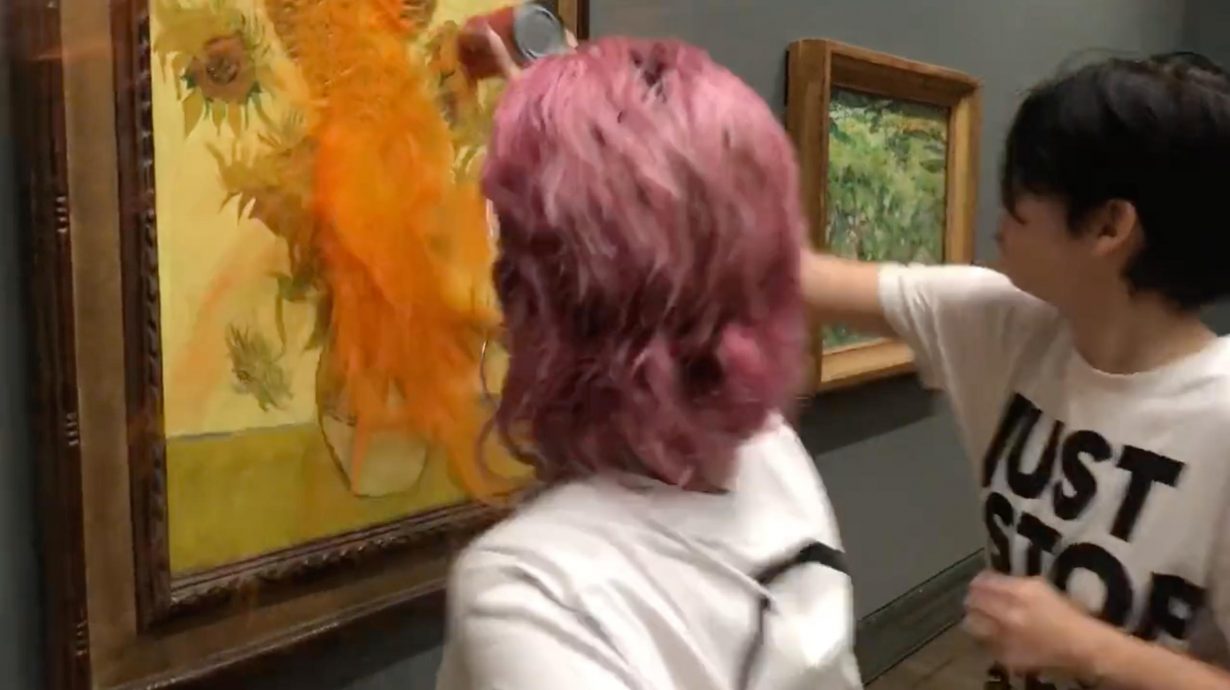

To misuse Édouard Glissant’s best-known metaphor, the contemporary art scene in 2022 resembled an archipelago. And one, moreover, in which there was limited interaction between its scattered isles. The Island of No Money, for example – as exemplified by the so-called ‘NGO aesthetics’ of ruangrupa’s problematic but conversation-changing Documenta and by a substantial tranche of reparative, ‘care’-inclined institutional programming – appears far removed from the Island of Almost All the Money, aka the auction houses. In the latter, prices of $100–150 million for a painting are being normalised (and if you were buying a Warhol Marilyn at Christie’s this May, make that $195m), and hardly anyone in these gilded salesrooms is looking at those noisy, righteously indignant protestors chez No Money, with their resistance to commodities and fondness for limited-time events, music, food, etc. The chief manner in which protest and expensive art connected this year – aside from ongoing fundraisers for Ukraine, where seven Banksy murals also showed up recently, and Pussy Riot funding themselves by performing at Art Basel Miami Beach – was through the Gen-Z media savvy of the Just Stop Oil activists. The latter’s divisive, virality-chasing dousing of glassed museum artworks with comestibles more arguably constituted 2022’s most visible aesthetic innovation, inside of galleries at least: mixed media for end times.

The common hallmark of all the above is extremity, along the vectors of finance and feeling. Outside of this there were – as always – some great individual exhibitions; but this isn’t a top-ten list, as single shows don’t tend to concretise trends. Contrarily, as was apparent if you foolhardily entered any art fair this year with ambitions other than ethnography, the commercial scene (aka the Island of the Rest of the Money) remains primarily infatuated with OKish painting. In an upgrade on the last few years, though, the market increasingly favours both kinds of OKish painting, figurative and abstract, like that bar in The Blues Brothers that offered both kinds of music, country and western. Plus, it’s skewing younger and towards figures comfortable being profiled in fashion magazines, with galleries increasingly keen to chivalrously rescue adept young daubers like Anna Weyant, Louise Giovanelli and Jadé Fadojutimi from spending any time languishing in the post-graduation wilderness. In museums, too, and on the level of plaudits, representation continues to improve for women and artists of colour – Black women won the Turner Prize and Golden Lions at Venice this year – though, according to the latest Burns Halperin Report on the demographics of institutional purchasing, this isn’t translating into museum acquisitions, and the relative permanence and visibility they represent.

Moving on, let’s fly over that flashy, recently minted Island of NFTs. As a marketplace, at least, it almost sank during this year’s cryptocurrency crash, when values for said New-Fangled Tulips (did I get that right?) fell by 60% between Q2 and Q3. The separation of technology and pure speculation in this case, nevertheless, might not be a bad thing. NFTs themselves seem likely to survive as a format, and to evolve as artists consider them less as static objects, like a dumb cartoon image, than as virtual assets bundled with physical ones, or as dynamic processes – Ian Cheng’s recent 3FACE (2022), for example, a bespoke portrait of sorts that modulates based on the evolving contents of the buyer’s cryptocurrency wallet. (Art that banks on a well-heeled audience revealing their assets was a micro-trend this year: see Brooklyn art collective MSCHF’s ATM Leaderboard (2022), again at Art Basel Miami Beach, a cash-machine scoreboard of visitors’ account balances.)

Such an alliance of generative art like Cheng’s – whose time has been coming for decades – with the decentralised economy of NFTs feels, although nascent, like a more salient use of the technology than the somewhat ridiculous and roundly criticised launching of Hilma af Klint NFTs via the what-is-this-timeline pairing of Acute Art and Pharrell Williams’s digital art gallery, GODA. Tech, too, is driving another emergent narrative: the democratisation of image-making, thanks to newly non-glitchy AI programs like Dall-E 2, Midjourney and the like. Artists are using such programs themselves: in the case of Jon Rafman’s recent work, fiddling with prompts to locate new territory in abjection and grotesquery (albeit without generating anything as creepy as Loab, the nightmarish female figure who keeps inexplicably popping up in AI art). But seemingly everyone else is having a go too and the resultant images circulate widely, which is beginning to result in sheeny visual weirdness becoming counterintuitively familiar.

In terms of infrastructure, earlier this year unconfirmed rumours swirled that the luxury brand LMVH was buying, or extending a line of credit to, Gagosian. The consensus was that even if it wasn’t happening, it was highly thinkable, even logical: Gagosian, too, is highly corporate and a luxury brand, its client base overlaps with that of LMVH – whose owner Bernard Arnault is currently the world’s richest man – and art in any case is increasingly swirled together with other aspects of high-end lifestyle as ostentatious proof of wealth. (See also Hauser & Wirth’s art-filled fancy hotel in the Scottish Highlands, a stone’s throw from Balmoral, plus their restaurants, pubs and members’ clubs; Frieze founders Amanda Sharp and Matthew Slotover’s London restaurant Toklas; and Slotover’s recently opened hotel in Margate.) When art itself is just a lifestyle trinket, of course, qualities like recognition factor and superficial attractiveness become more important than anything else, which makes matters quite dull for anyone who associates art with being challenged. Super-rich people plundering and despoiling everything of worth is a twenty-first-century narrative that has yet to go into reverse, so we can safely expect more of that in 2023, even if we don’t know quite what form it’ll take. (A mega-gallery hasn’t bought an art magazine yet, thankfully, though that doesn’t stop the likes of those mentioned above creating their own.) But another thing that doesn’t change is that art always reacts to itself, turns on itself. And if you don’t like a given island, choose another.