A sprawling group show at Frankfurt MMK explores what it means to live with, care for and value bodies with disability

With the phrase ‘crip time’, academic Alison Kafer refers to the imperative for a new way of thinking about and understanding time in a way that acknowledges different lived realities. By borrowing a phrase most often associated with disability studies, this sprawling show with 41 artists, almost all of whom experience disability, aims to explore what it means to have, care for and value bodies and minds with different needs – an approach in which definitions are often set aside in favour of seeing things anew and from different perspectives. Some works play explicitly with the notion of time itself, including Shannon Finnegan’s clocks that are divided into days of the week rather than hours and have hands moving at various tempos (Have you ever fallen in love with a clock?, 2021) as well as Sharona Franklin’s Crip Clock (2021), which features six silver spoons holding pills arranged like six stationary clock hands, the spoon handles meeting in the centre and extending outward so the bowls appear where one might expect to see 12, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10; time here is marked not by seconds or minutes but by a medication schedule. Other pieces, meanwhile, address different spectrums of disability – everything from modes of communication to interdependency to the cost of medical care to the effects of HIV/AIDS, depression and substance addiction.

On the ground floor, Emilie Louise Gossiaux’s two papier-mâché sculptures show her guide dog, London, standing on hind legs as if dancing, welcoming visitors to the exhibition. The works are backdropped by Christine Sun Kim’s giant mural Echo Trap (2021), which uses musical notation to concretise the American Sign Language sign for ‘echo’. In another room, Liza Sylvestre, in her video Wha_ i_ I _old you a _ _ory in a language I _an _ear (2014), recounts a childhood memory about hearing: she would turn on a boombox, place her hands on the speakers and turn the volume up to the maximum level. In the video’s first half, she stares into the camera, focused, enunciating every word clearly, but in the second half she recounts the memory by enunciating only the parts of each word that she can hear (“with so much”, for example, becomes “wi_ _ _o mu_ _”), the sentences turning into fragmented letters and sounds as tears well up in her fixated eyes. Nearby, golden-wrapped candies from Felix Gonzalez Torres’s Untitled (Placebo – Landscape – for Roni) (1993) spill out from a room that is usually accessible only via stairs; by covering the stairs with candy, the piece renders the space inaccessible to all. London, meanwhile, later makes another appearance in a series of Gossiaux’s drawings, one of which combines their bodies, a reference to their dependence on each other and inseparability.

Courtesy the artist and MMK, Frankfurt

Over the next two floors, personal experiences continue to be reflected in works like Michelle Miles’s video hand model (2018): images of hands holding objects are paired with audio and corresponding captions that relate her engagement with a modelling agency which, after receiving her headshots, wanted to sign her. When they discovered she used a wheelchair, they revoked the offer and said she was of no use to them, to the industry. Both Jesse Darling and Emily Barker point to the burden and cost of healthcare systems. For Epistemologies (Part of a series) (2019), Darling filled eight archival binders with blocks of concrete, alluding to the psychological weight of navigating healthcare systems. Nearby is Barker’s Land of the Free (2012/21), a framed bill from Northwestern Memorial Hospital for $506,088.35, the amount due after her insurance company had paid their share for her stay at the hospital. This is complemented by Death by 7865 Paper Cuts (2019), a towering stack of only three-years’ worth of Barker’s photocopied medical bills and lifecare plan.

Elsewhere, in the six-minute video Black Disabled Art History 101 (2015), Leroy F. Moore Jr. offers exactly what the title suggests, telling the abridged stories of people like Skelly, Wise and Apple, aka Israel Vibration, aka three people who met in a rehabilitation centre, were kicked out for their beliefs in Rasta, found themselves homeless and started singing on the streets, and are now regarded as the founders of reggae.

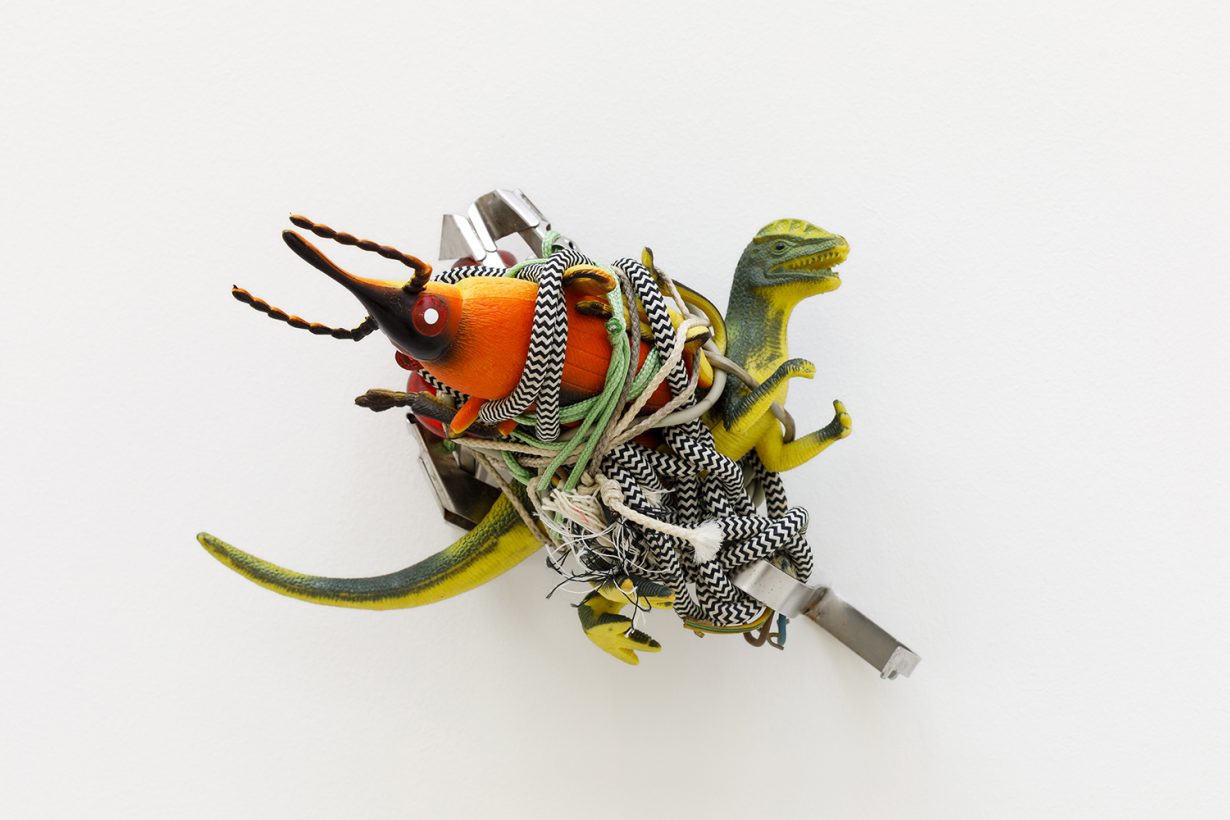

But among these explorations of experiences and ideas surrounding contemporary disability discourse are more obscure pieces. Take, for example, wall sculptures by Franco Bellucci. His beautifully and tightly wound knots of socks, rubber tubes, old tires and pipes convey a sense of pent-up anxiety, of rage, of determination. A toy pistol is contained in one, a dinosaur in another. Rather than his artworks, though, Bellucci’s biography appears to be what landed him in the show: he suffered a brain injury as a child and spent most of his life confined to a closed psychiatric ward.

Another curiosity is a wheelchair covered with a sheet of mirror foil by Isa Genzken (Untitled, 2006), who is diagnosed bipolar. The wheelchair could be read as a comment on the relationship between mental and physical health, or evident ‘disabilities’ compared to those unseen, but when placed alongside works by artists who are wheelchair users, it takes on a different air. The accompanying exhibition booklet, which offers indispensable insight and useful background on the vast majority of works in the exhibition, especially those that are more conceptual, problematises the work even further: Genzken is among the artists who were apparently deemed ‘too famous’ to warrant an explanatory text (the others missing are Wolfgang Tillmans, Nan Goldin and John Akomfrah, though Tillmans’s photograph of his medications, Goldin’s video installation about substance abuse and her sister’s suicide, and Akomfrah’s film on illness and death are autobiographical and more self-explanatory). With these inclusions, the show veers into the territory of tokenisation, seeming to categorise work solely based on biography or materials used.

Moreover, the only reference to contemporary disability issues in Germany is in For the 12 disabled people in Lebenshilfehaus (Area of Refuge) (2021), by Chloe Pascal Crawford, an American artist whose site-specific installation is a homage to the group of people with disabilities who died during the floods in southern Germany earlier this year. And in this context Gerhard Richter’s Tante Marianne (Fotofassung WV 87) (1965/2018) – depicting himself as a baby with his then-teenage aunt, who was later diagnosed schizophrenic and then murdered during Nazi euthanasia programmes – feels like an abrupt, unnecessary aside. Furthermore, both Richter’s and Genzken’s works point to the fine line between disabled artists and nondisabled artists who have relationships with disabled people. This line must be navigated carefully, from both curatorial and artistic perspectives: when it’s not, the result risks coming across as appropriation.

Zooming back out, to understand the show as a whole it is important to recognise ‘disability’ as ‘a site of questions rather than firm definitions’, as Kafer writes in Feminist, Queer, Crip (2013). At its best, Crip Time succeeds in exposing social and political injustices related to disability, as well as in helping a viewer reframe their own perception of what ‘disability’ is, notably through its refusal to provide definitions or neat categories. But to understand and appreciate a site of questions, there must also be a clear framework of the topic at hand. Here, the deeper I engaged, the more that framework – already vague and raw to start – seemed to slip away.

Crip Time is at Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, until 30 January