The threat posed to the city’s progressive galleries and queer artists following the reelection of the conservative AK Party this May suggests profound changes still to come

Hours after Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his conservative AK Party triumphed in the first round of presidential and parliamentary elections this May, Turkey’s authoritarian president emerged on live television. The autocrat, relaxed and smiling, was opening the new building of Istanbul Modern, Turkey’s first modern art museum. Here stood the populist who campaigned on a post-truth, anti-queer platform for months, waxing lyrical about Istanbul Modern’s place in Turkey’s cultural tourism industry and attacking “vandals” who protested against his government in 2013’s Occupy Wall Street inspired Gezi Park protests. For a moment, I spotted one of the museum’s founders joking with Erdoğan’s chief of communications, who engineered the AKP’s anti-LGBTQ discourse. It was an embarrassing sight. After the ceremony, friends in Istanbul’s artistic communities mocked me for being so surprised. Was I not aware that Istanbul Modern, which sits on the city’s precious coastline with the Bosphorus strait, had benefited from Erdoğan’s two-decades-long economic policies of public-private partnerships from the start? Wasn’t Erdoğan one of the architects of what the New York Times memorably named in 2012 ‘the Istanbul Art-Boom Bubble’?

Istanbul Modern’s original location was a dry bulk warehouse built for Turkish Maritime Enterprises which was first repurposed as a venue for the Istanbul Biennial in 2003. Turkish private capital began transforming the derelict place into a sleek art space, and a year later, Istanbul Modern was born. At the opening, the founders described the museum as ‘strong proof of Turkey’s European aspirations’ and thanked Erdoğan for ‘allowing the warehouse to be handed to the museum’. The rise of Istanbul as a potential hub for contemporary art in the Middle East was tied to the rise of the AKP from the get-go. By the time Istanbul Modern emerged, the three-year-old ‘conservative democrat’ party was engaged in membership negotiations with the European Union.

As the AKP’s ‘European aspirations’ fizzled over the following decade, Istanbul Modern, a symbol of the best-of-both-worlds era of Turkey (cool, liberal, and Islamic) in the wake of 9/11, began to appear anachronistic, increasingly so after 2013’s Occupy Gezi events, when the government no longer concealed their rigid core and clamped down on thousands of progressive activists. By 2022, one of Istanbul Modern’s nine board members, a former AKP apparatchik, could freely express support for Russia in its illegal annexation of Ukraine, proclaiming, ‘If Russia falls, Turkey will get divided’, and calling Turkey’s NATO membership ‘shameful’. Not surprising, then, that “nobody cares about Istanbul Modern any longer”, as Kültigin Kağan Akbulut, who runs the pro-LGBTQ art journal Argonotlar, put it so lucidly to me recently. The museum’s team surely wanted to leave that legacy behind with the new building, I naively assumed before Erdoğan’s opening ceremony. So what were they thinking?

In 2014, the Genoise ‘starchitect’ Renzo Piano was commissioned to design the new Istanbul Modern and two years later, the original museum building was closed to the public. Since then, Turkey has seen numerous political, cultural and sociological transformations. With its arts patrons, journalists in jail or exile, and its 150-year-long parliamentarian democracy legacy in tatters, Turkey has shifted to an illiberal state since Piano began work on the new building. Yet you couldn’t tell any of that from the reopening of Istanbul Modern’s artistic offerings this summer. Always Here, a pop-up exhibition funded by Bank of America, brought together works by a set of women artists from Turkey, including Nilbar Güreş and Güneş Terkol. Istanbul Modern also commissioned works by two male artists: Olafur Eliasson’s Your Unexpected Journey, a site-specific installation of three geometrical spheres furnishing Piano’s transparent central stairwell, and Refik Anadol’s Infinity Room Bosphorus, a room of mirrors splashed with wave-like patterns that claim to explore how data is ‘related with the continual transformation of the Bosporus caused by weather’.

Walking through the galleries, I was reminded of 2014, when Istanbul Modern placed Rainbow, a 7.5 m x 15 m neon installation by the Turkish-Armenian artist Sarkis on its facade in what many read as a political gesture. The rainbow didn’t feature on the front of the new building. Instead, Istanbul Modern contained Sarkis’s work inside a gallery devoted to the artist. Call me naive (again), but to attend the opening of an international modern art museum in the middle of Pride Month and encounter no sign of, or reference to, the queer community, still came as a surprise. “There is a cunning homophobia and transphobia in these institutions”, Istanbul-based artist Marina Papazyan explained to me over the phone. Papazyan, who uses they/them pronouns, expects “silent collaboration” with the state from Turkey’s art institutions in the post-election era. “They’ll push LGBTQ people to more solitude in a plausibly deniable way. Possibly, artists will feel some things are no longer possible in Turkey, and this will soon solidify into a cunningly altered novel status quo.”

Since 2014, when Erdoğan became president, verbal and physical violence against LGBTQ communities has slowly risen and Pride and Trans marches have been banned. Last year, Turkey’s president branded Turkey’s queer communities ‘deviants’ who threaten Turkey’s ‘family structure’. He promised to ‘tackle’ the LGBTQ ‘issue’ for good. In response, many NGOs collaborated with and supported LGBTQ causes: The Citizens Assembly, for example, offers professional support to LGBT asylum-seekers in Turkey. Not so Istanbul’s sleek art institutions and museums, many of which are partly funded by the government. While local bars and clothing brands added rainbow symbols to their social media avatars to express solidarity, Istanbul’s major art institutions have remained silent on LGBTQ rights for years. For Emre Erbirer, a culture manager and programme curator who uses they/them pronouns, this is a moment in which “you’re either with us or we no longer exist”. The rainbow, they said, “has turned into such a hate object today that Istanbul Modern can’t display it outside their building. They lack the courage, both institutionally and on a personal level.” Such deference has haunted art institutions since Erdoğan won the May elections.

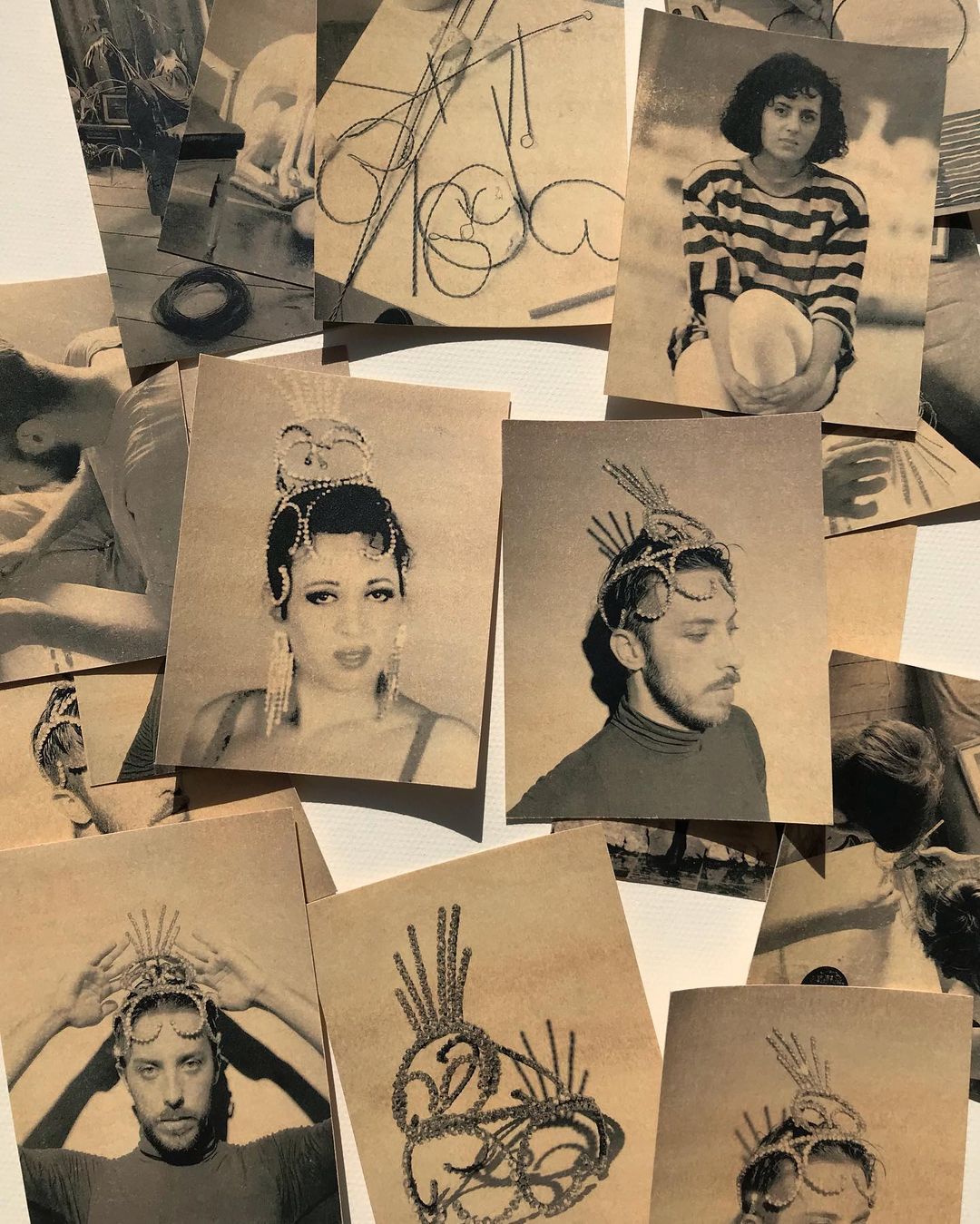

Independent art spaces are braver. They don’t rely on public funding and keep a principled distance from the Turkish state. DEPO, a former tobacco warehouse operated by the imprisoned arts patron Osman Kavala, and Kıraathane, a journalist-run literary cooperative that recently expanded into an art space and showed works by the imprisoned Kurdish artist Zehra Doğan’s work in Turkey, for the first time in 2020, have proved how change can come about with seemingly small but persistent acts of bravery. DEPO was the only significant artistic venue in Istanbul to host a queer exhibition during Pride Month this year. Resurgence in Fragments, a group show by Okyanus Çağrı Çamcı, Üzüm Derin Solak, and Furkan Öztekin (through 5 August). Featuring family heirlooms, whistles and Pride flags, the personal archives of these artists have morphed into a queer quill with which they write a history of their own. Another outspoken voice in Istanbul’s widely muted art sector is the Pera Museum, owned by the progressive Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation, whose film department curated a program for this year’s Pride Month. Who Wouldn’t Want a Better Story? (through 19 July) screens a flurry of fine queer films, including Peter Strickland’s The Duke of Burgundy (2014), Isabel Sanoval’s A Common Language (2020), and Days (2020) by the peerless Tsai Ming-liang.

Last month’s attack on ArtIstanbul Feshane, a restored nineteenth century fez factory, was a reminder of the current risks for art spaces who choose to platform LGBTQ artists in Turkey. Days after its opening, the venue’s inaugural exhibition was closed when conservative activists gathered outside the building on June 27, decrying Ingres (2015), a pointed work by the hyperrealist painter Taner Ceylan who placed the head of Ingres on the body of Princess de Broglie to illustrate Oscar Wilde’s famous maxim, ‘Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter’. This, the pro-government news network A Haber claimed, was ‘LGBT propaganda’ and part of a ‘perverted exhibition’. (The venue reopened hours after protesters dispersed.)

With Erdoğan’s reelection, it remains unclear what the future holds for the LGBTQ community. Akbulut, the Argonotlar editor, expects a significant clampdown soon. “They’ll shut down one of the smaller LGBTQ organizations. The government feels it needs to give something to its radical supporters. They’ll emphasise family values and wage an anti-rainbow culture war.” Papazyan predicts a subtle change: “in a few months institutions may start saying, behind closed doors, ‘Let us not support artists who identify as queer in their applications so as not to face problems.’” This “basic and banal reaction”, Papazyan adds, can become an “institutional mechanism designed to secure maximum self-preservation.” Erbirer was more blunt. “If you don’t stand with us now, our blood is on your hands. You’re guilty, because we’ve arrived at a point where you can no longer ignore what they’re doing to us.”

Kaya Genç is a journalist and novelist from Istanbul. His most recent book is The Lion and the Nightingale: A Journey Through Modern Turkey, 2019