Anthropologist, occultist, music historian, filmmaker, artist, paper-airplane collector, greeting-card designer, shaman- in-residence, consecrated bishop, gnostic saint and all-round hipster, he defied convention and any kind of categorisation – and now he’s the subject of a major museum retrospective

If you’ve never heard of Harry Smith, then perhaps the most obvious entry point is Anthology of American Folk Music. Released in 1952, this six-album collection of 84 blues, folk, country and gospel records was drawn from the then-twenty-nine-year-old, Oregon-born Smith’s own obsessive, itinerant and effortful stockpiling of obscure and out-of-print commercial 78s. (Moe Asch of Folkways Records convinced Smith to compile the album after the latter came to him, characteristically broke, attempting to hawk his collection for cash.) Anthology’s release was hugely catalytic: it led directly to the folk revival in 1950s America, thence to young people listening to politicised lyrics; from here, one can argue – as Allen Ginsberg has – that it led to a raising of political consciousness and the explosion of the counterculture.

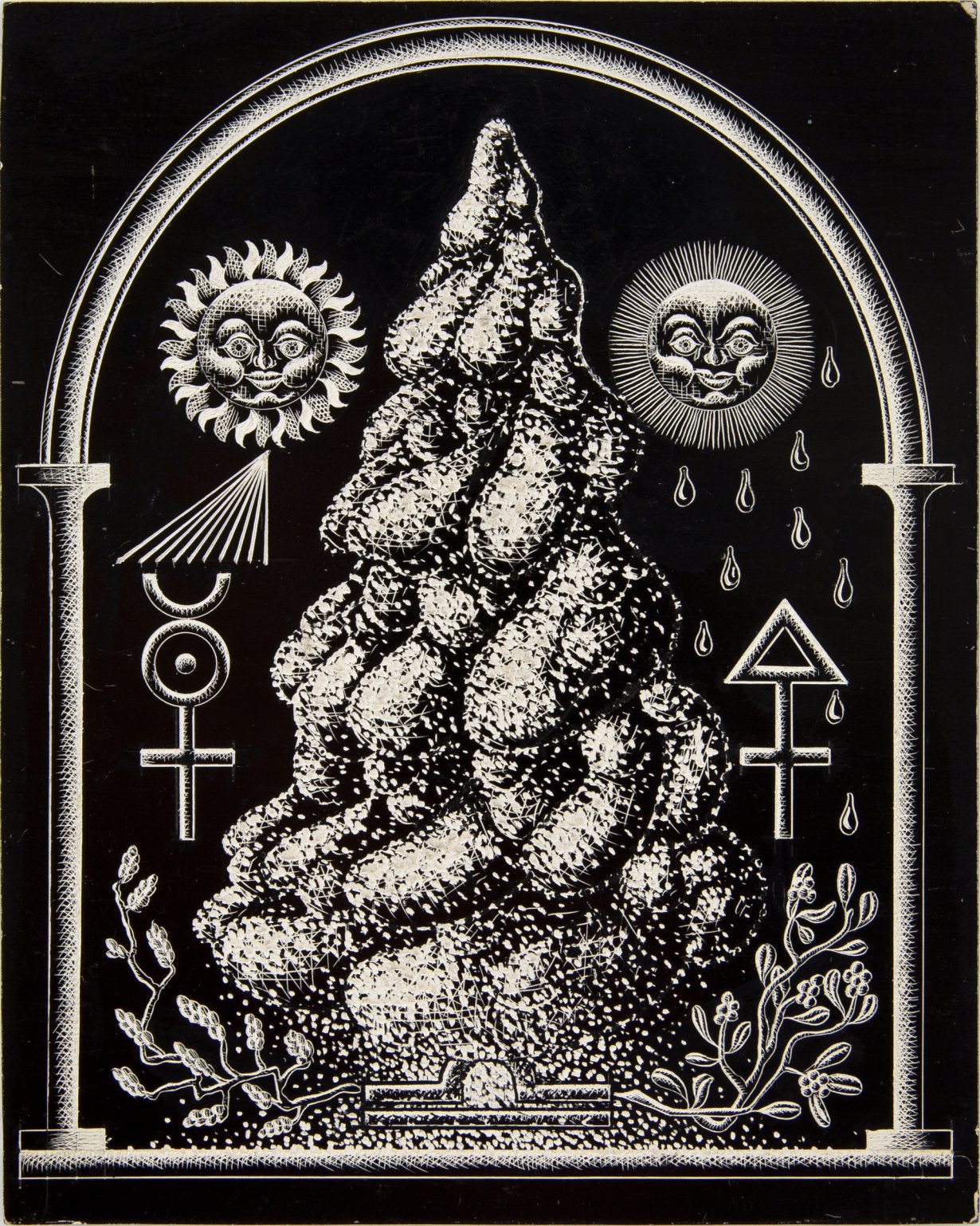

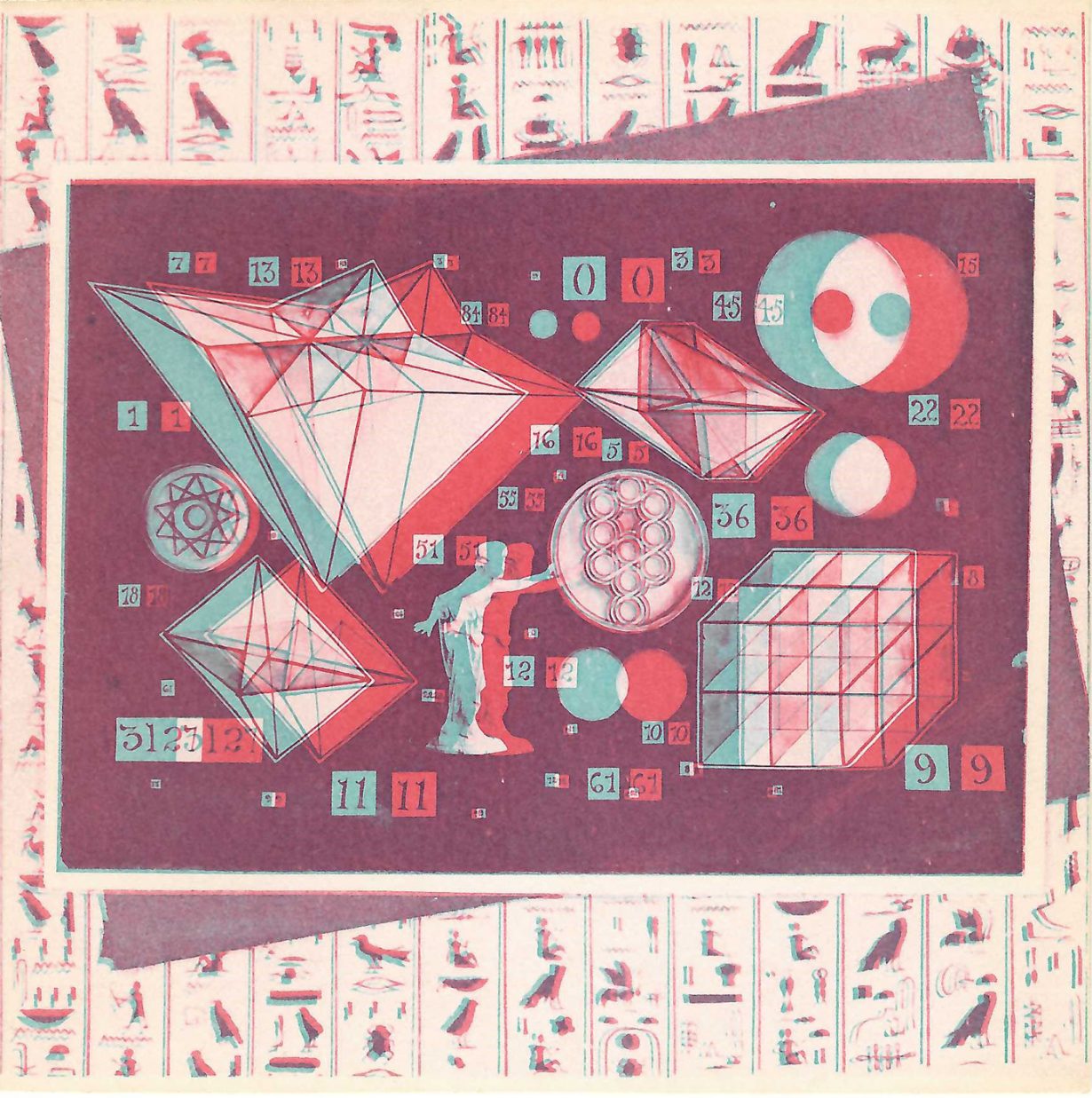

Indeed, Smith himself claimed to expect as much: ‘I felt social changes would result,’ he stated succinctly in 1968. This might seem presumptuous, but Smith was nothing if not an egomaniac. But note that the cover of Anthology, which features an illustration – from a book on mysticism by Elizabethan-era English physician and occultist Robert Fludd – of a musical instrument called a ‘celestial monochord’ being tuned by the hand of God; its three double albums are colourcoded red, green and blue to reference the dynamic elements (fire, water, air), and the songs themselves were dispatches from a fogbound lost world, full of ghosts, murders and spooky cockeyed meanings due to folk lyrics changing over time. Anthology, music critic Greil Marcus wrote when the records were reissued during the 1990s, was ‘an occult document disguised as an academic treatise on stylistic shifts within an archaic musicology’. It testified in its very packaging not only to the various levels on which its compiler was thinking and working, but also to the cosmic power of culture.

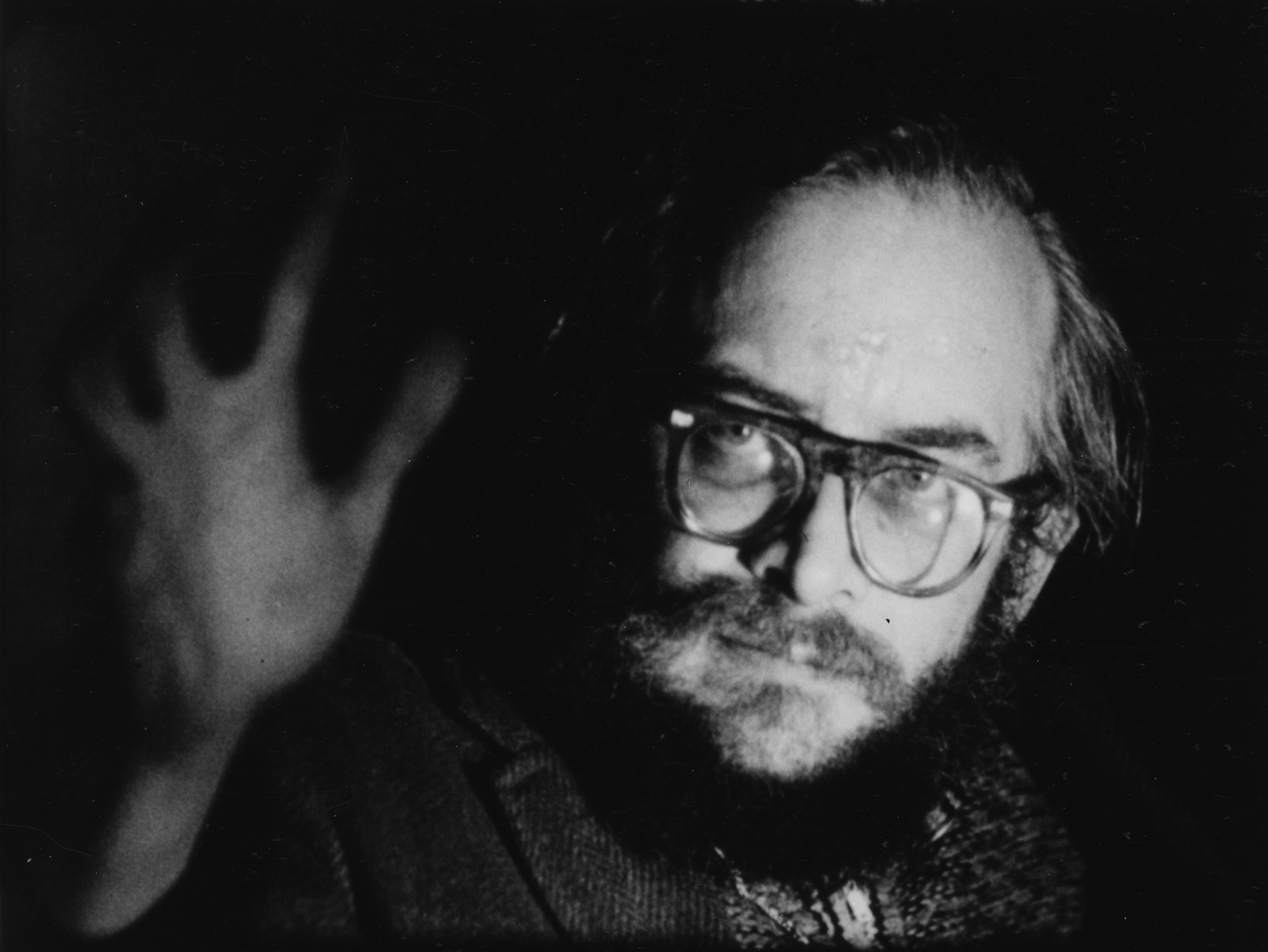

Harry Everett Smith, who was born in 1923 and died in 1991, was a lot of things. Wikipedia describes him first as a polymath, then as an ‘artist, experimental filmmaker, bohemian, mystic, record collector, hoarder, student of anthropology and a Neo-Gnostic bishop’. The title of an unbridled oral history that Semiotext(e) published in 1996, meanwhile, rolls all his roles into the phrase American Magus. Does any of that help to articulate what Smith was? Perhaps not, but there is the promise of a clearer reflection in New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art’s upcoming retrospective exploration of Smith’s many-sided activity, Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: The Art of Harry Smith. (This year marks the centenary of Smith’s birth, and the publication of John F. Szwed’s new biography, Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith, was clearly timed to fit; the museum’s exhibition, however, has been in the making for around a decade, due to various false starts and rethinkings, and wasn’t deliberately planned for this year: as with many things in Smith’s life, strange forces were at work.)

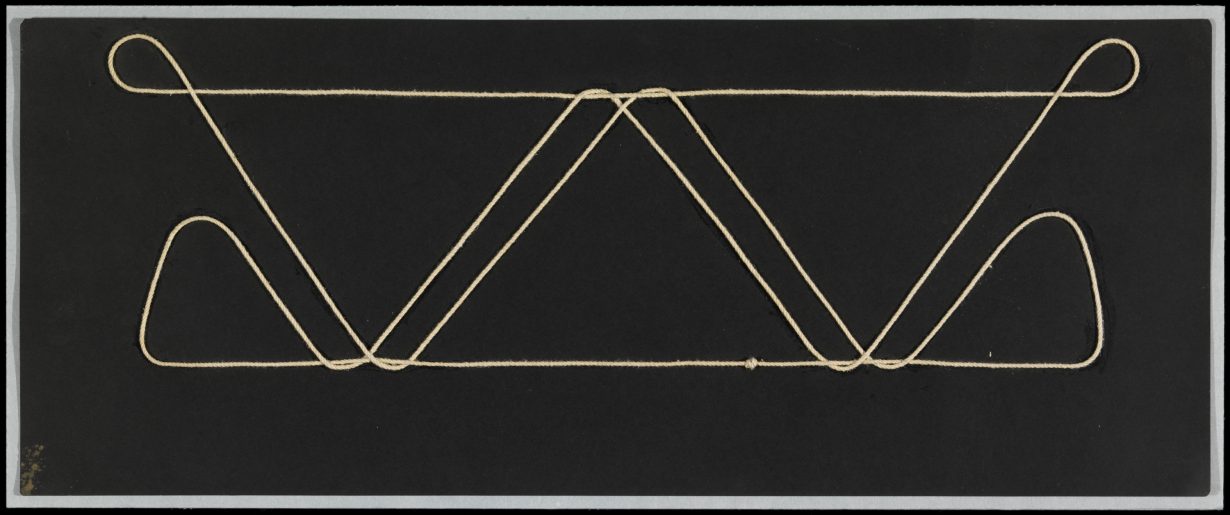

Indeed, a simple outline of some of the items in the show suggests the bewildering range possessed of this obstreperous hipster-Zelig, who was known equally for spectacular erudition and for loudly chewing out his friends and, on occasion, smashing up his own work. If Smith’s self-characterisation was primarily as an anthropologist – the discipline in which he trained – and a preserver of cultural artefacts, we see on display documentation of his teenage recordings of Lummi Native American rituals and dances on a reservation in Washington during the early 1940s. Around the same time, he began collecting string figures, seeing in them evidence – the same coded designs showing up in wildly different places – of mass migrations that eluded the history books. Meanwhile, he was starting to make paintings and hand-painted films; by the late 1940s, living in San Francisco, a city that was then rather more avant-garde than New York, he was creating films to accompany bebop musicians; he then began making patterned abstract paintings, full of circles, loops, connecting lines, paisley blots and ladderlike forms, based on the improvisations of Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk et al.

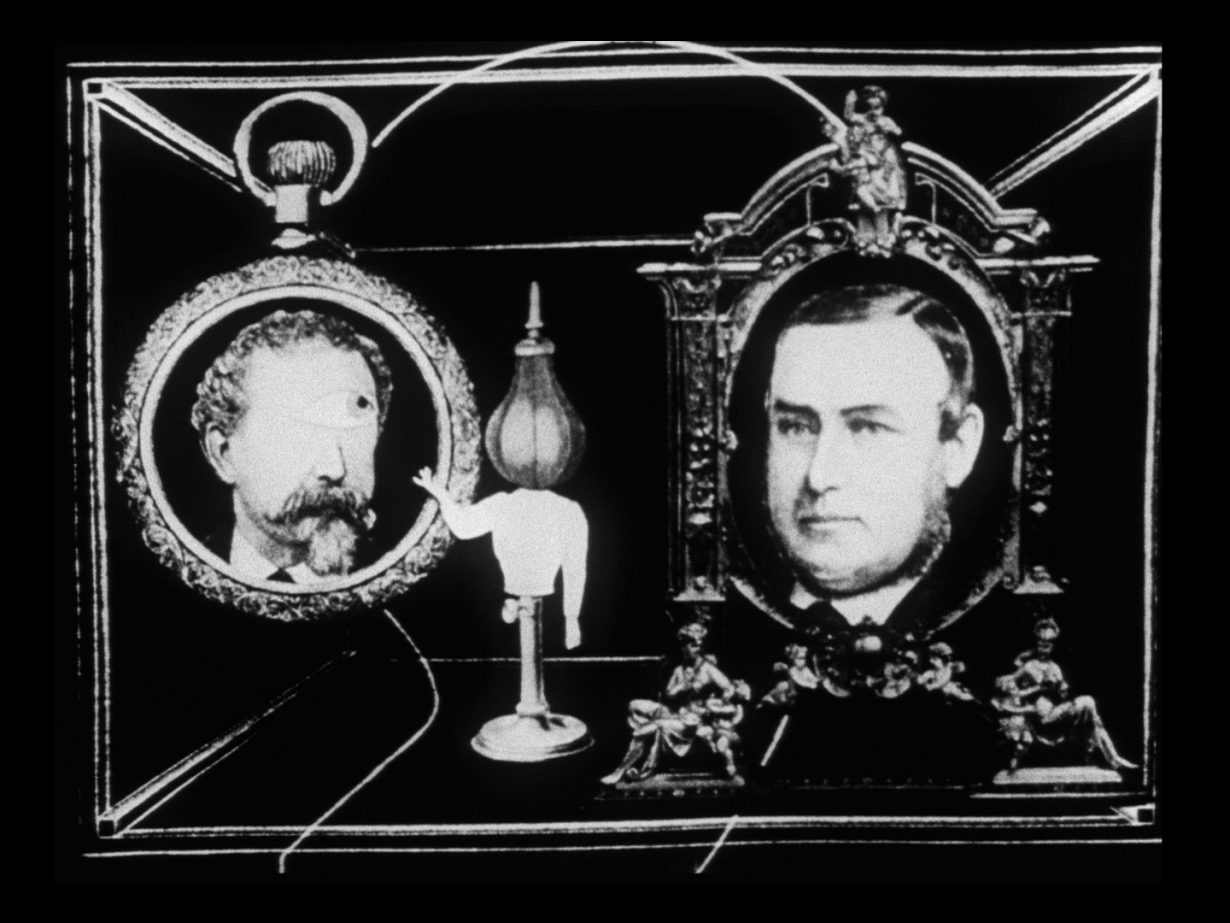

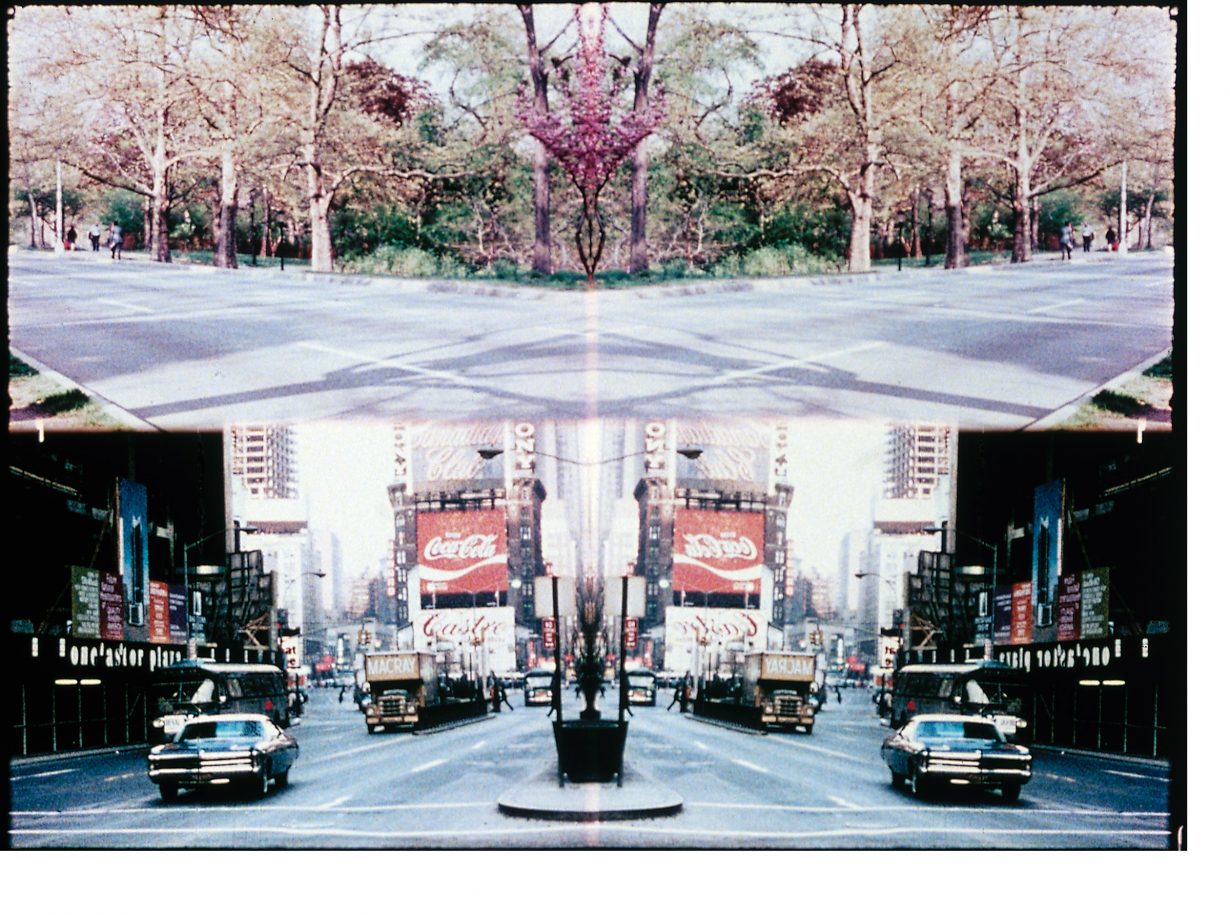

In New York, where Smith lived from the 1950s onwards, he met Ginsberg (who became a longstanding supporter); began studying mysticism in earnest, particularly Kabbalah and the works of Aleister Crowley; and alongside other pursuits (meticulous scratchboard illustrations and drawings; amassing a vast collection of found paper airplanes) made increasingly ambitious and intricate films. Some of these, like the black-and-white animation using cutouts from Victorian catalogues to depict a series of alchemical transformations, Film No. 12: Heaven and Earth Magic (1957–62), were supposedly meant to run for six hours (the existing cut only lasts for one). Others, like Film No. 18: Mahagonny (1970–80, rarely seen outside of this show), were ensnared in production difficulties, and the various custodians of Smith’s work have strong opinions on how they should best be shown. (Smith himself at one point wanted to present this work on a tipped-up boxing ring, referring back to a 1920s staging of the Brecht/Weill opera from which his film’s title is borrowed.) Amid all this, he made (during the 1950s) Kabbalistic designs while working at an adventurous greetings card company founded by poet Lionel Ziprin, collected huge numbers of tarot cards, popup books, gourds, Seminole textiles and Ukrainian painted Easter eggs, among other things, and studied myriad languages and dialects. As the Whitney puts it in the show’s press release, he ‘created a life and practice largely outside of institutions and capitalism’, though another way of putting that is that he expected support from others for his genius and existed in constant financial chaos and, after much of his work was stolen – seemingly by film production creditors in 1964 – disconsolate drunkenness. In his last years, he was ‘Shaman-in-Residence’ at the Buddhist-inclined Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

This apparent diversity of interests and freewheeling mode of living – much of Smith’s compulsive material practice has been ‘found’ in the apartments of people with whom he couch-surfed, and some only exists in photographic documentation – looks like it could prove a challenge to curators, and equally result in a dry, archival show. But Fragments of a Faith Forgotten is unlikely to be that; first because its exhibition designer and cocurator is the artist Carol Bove, a longtime Smith aficionado (“Harry Smith is my religion,” she once said to me), whose involvement with his practice began when she incorporated a display of Smith and Ziprin’s collaborative work into a 2013 exhibition of hers. Bove has driven the present show forward since its inception, liaised between the various parties who claim stewardship over Smith’s archives, turned up new research, given shelter to multiple fragile archives and also designed what she describes as “exhibition furniture” for the exhibition’s scenography.

Additionally, Fragments very much looks like it’s going to present a take on Smith. In researching, Bove says, she discovered that contrary to his constant self-presentation as a ‘holy fool’ separate from – or above – the avant-garde of his time, which he professed to disdain and be outside of, Smith was in dialogue with and responsive to the artistic currents around him. That, apparently unknown until Bove quizzed the right people, he’d seen Jackson Pollock’s pre-Abstract Expressionist work at SFMOMA in 1945, and his own paintings’ highly similar aesthetics weren’t produced in a vacuum. That his mid-50s paintings based on jazz improvisations, meanwhile, which might be framed as backwards-looking post-Surrealism at the time, were more likely a cranky rebuttal of fashionable Ab-Ex aesthetics at a moment when the collectors’ market was developing in New York, and ‘selling out’ was first an issue.

At the same time, though, and despite this show being located in an art museum, Bove and the other curators don’t seek to reclassify Smith as ‘merely’ an artist (something he himself resisted) and thus reduce his wider ambits. His largescale collections of artefacts, and his habitual fashioning of links between apparently disconnected things (sound and image, for example, or ethnographic artefacts from seemingly different cultures), Bove sees as the outsize, one-man service of preserving a library, at least in microcosm; preserving human culture, even. And given that Smith studied hermeticism to a very high level – he was a consecrated bishop in the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica, the ecclesiastical wing of the secret society the Ordo Templi Orientis, who said a gnostic mass for him after his death, and canonised him this year as a ‘gnostic saint’ alongside William Blake, Giordano Bruno and others – it’s apparent that Smith had higher-than-human aspirations for self-realisation, and was courting some obscure energies. (In keeping with this, as Bove suggested to me, strange things start to happen when you engage with Smith’s work. A week after I began researching this text, a visitor to my home, whom I’d never met, turned out to have come directly from spending time with her friend Rani Singh, director of the Harry Smith Archives. It wouldn’t be too hard, equally, to imagine this show’s protracted gestation being due to Smith meddling irately from his cloud.)

Approach Fragments how you will, then. On one level, as is acknowledged by the show giving upwards of a quarter of its floorspace to a listening environment for Anthology, Harry Smith preserved some great old records, to galvanising effect; as he said when accepting a Grammy award for Lifetime Achievement in 1991, he was “glad to say my dreams came true. I saw America changed by music.” He was one of the great avant-garde filmmakers of his time (and knew it: in one of his scattered notes, he placed himself third behind Warhol – whose 1964 Screen Test of Smith is in the show – and Kenneth Anger). He’s part of a lineage of unclassifiable mystics, however much his cantankerousness and grandiosity might have obscured it. It’s 32 years since Smith died; he always said, characteristically, that his work wouldn’t be understood for at least 50. Now, in his old home- town, Smith is here again, but he’s also quite probably waiting for us around the bend.

Fragments of a Faith Forgotten is on show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, through 28 January