To reduce the artist’s portraiture to merely a triumph of representation is to miss the point of her work

In Being Here, Barbara Walker’s retrospective exhibition at the Whitworth Gallery, the wall texts which accompany the six major series on display imply that her primary concern is the visibility of those quietly erased by environments of racial and gendered dispossession. This framing is partly to be expected, given that Walker is a Black woman figurative artist working in Britain, whose 25-year career is being acknowledged in her first major survey show. Using the work of Kerry James Marshall and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye as examples of intricate formal experimentation, critic John-Baptiste Oduor notes how the historic exclusion of Black artists from major galleries in Europe and America has produced what he calls a ‘moral response’ to their inclusion. It is a corrective, he finds, which often obscures the complexity of the work at hand and curtails critical engagement, particularly for Black figurative artists.

Walker’s earliest oil paintings, created as an art student at Birmingham City University between 1998 and 2002 (which form part of the Private Faces series) are vibrant portraits of members of the Afro-Caribbean community in Birmingham derived from photographs. The largescale canvases deftly utilise light and shadow to produce a stark and affronting visual language. Walker’s compositions direct the gaze of the viewer through prolonged experimentation with her subjects’ positioning. Yet descriptions of this body of work at the Whitworth reduce it to merely a depictive celebration of the strength and resilience of Black being. Ironically, these meditations on her subjects’ visibility have the inverse effect of concealing the technique that produced them.

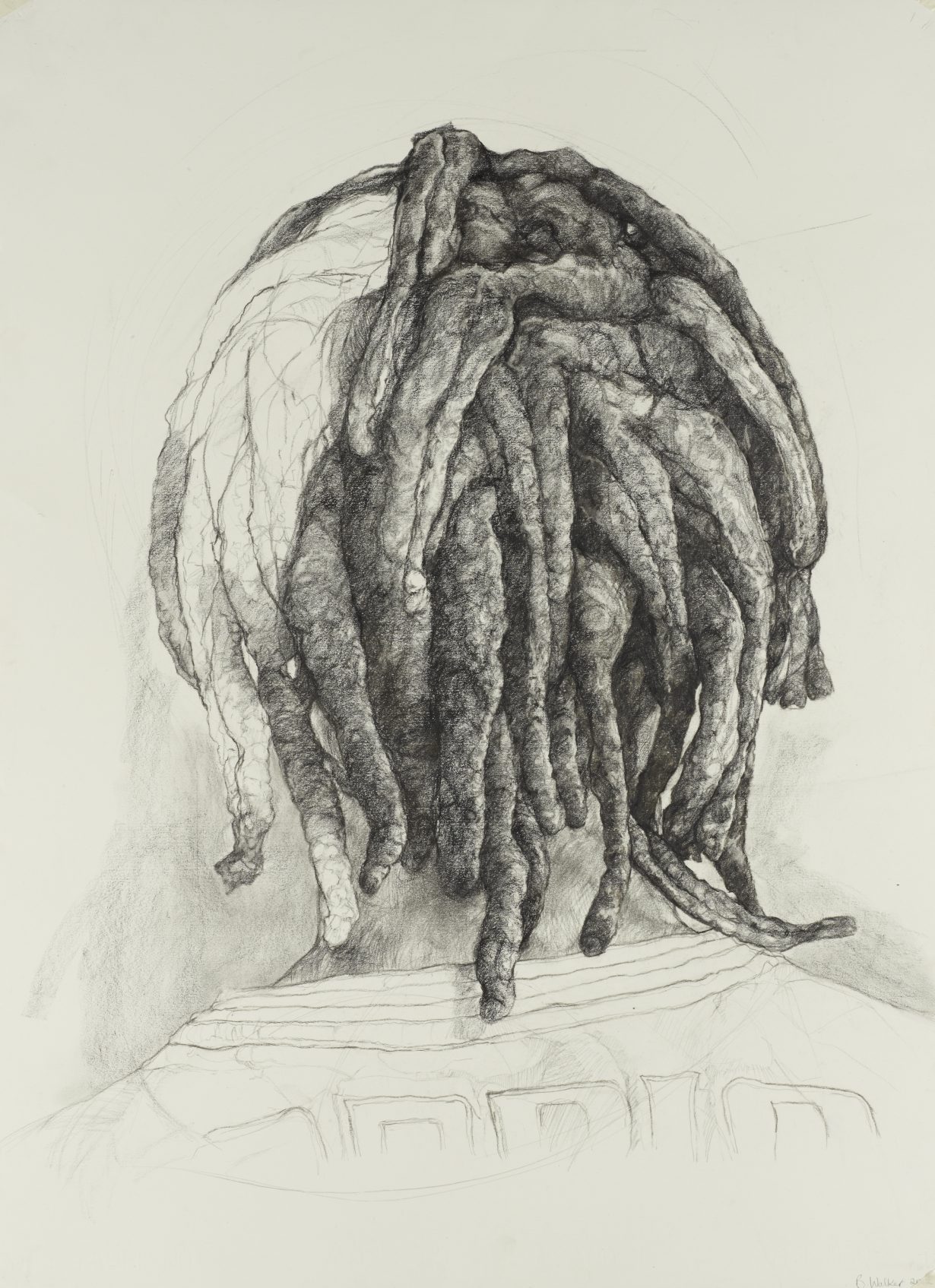

If visual art is a fertile medium for the discovery of what cannot be easily seen or comprehended, perhaps visibility is a compelling narrative worthy of examination. Walker herself believes in its potential. In the accompanying exhibition catalogue, she writes: ‘I love working with people who are not used to having their voices heard. People who are often made visible in the worst ways. I want to help make people visible in the best ways possible, by creating affirming images that speak of and to humanity.’ For Walker, visibility is less a self-evident preoccupation and more a conduit for the affirmation of Black life and presence. Indeed, the towering portraits in the Burden of Proof series (2022), mixed media with graphite, conté and pastel on paper, for which Walker was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2023, depict of members of the ‘Windrush Generation’ who have come to be defined as the victims of the Windrush scandal. In this act, Walker seeks to rescue the dignity of those whom the state has dehumanised, bringing these subjects back from the brink of erasure.

Her sitters are individuals whose de facto citizenship in the United Kingdom was revoked as a result of then-Home Secretary Theresa May’s implementation of the ‘Hostile Environment Policy’ in 2012. This policy introduced a new approach to immigration, one which forcefully thrust the onus to account for one’s belonging onto the migrant. The affective and physical reach of immigration control extended beyond national borders into the spheres of everyday life; routine ID checks of workers and raids of local businesses were legally mandated, while the Immigration Acts of 2014 and 2016 were designed to make it impossible for so called ‘illegal migrants’ to rent a house, a car, work or access healthcare. Walker intimately reflects back at us the human cost of such a policy using a drawing practice she describes as ‘a love letter’. The portraits, each detailed and deft with their iterative strokes, are layered on top of the documents that make the sitters ‘visible’ to the state and prove their right to remain in the United Kingdom – job descriptions from army posts, letters of recommendation from employers, a ‘Life in the UK’ Test. Every drawing is a sobering reminder of the bureaucratic necessity to justify one’s presence. You are not a person, Walker suggests, if you cannot prove it to the state.

Elsewhere in Being Here, we are told that the largest set of portraits in pencil adorning the wall of Whitworth Gallery will be washed away after the exhibition. The move is more than just symbolic; it is also a rejection of the artist’s authority to produce a subject through depiction and reproduce that subject via the display and circulation of work in a gallery space and art market. Art is not a means of accounting. Using the tools of visual representation, Walker asks, how does one render state sanctioned violence? The more ephemeral quality of pencil drawing also invites reflection on the question of impermanence. She succeeds in giving her subjects a sense of ontological security not because of who she depicts but how she depicts them. Her aesthetics express the knotty complexity of social life through form. Her forensic pencil markings, achieved through what Walker calls ‘labour intensive’ practices, long periods of physical exertion in which her whole body is used, emphasise not the audience but the sitter’s gaze, almost convincing us the portraiture may be enough to rescue them after they have been expunged.

But Walker’s practice is frustrated by the simple truth that it is impossible to account for a human being in their entirety: the state fails at it, and so does the artist. This is why questions of presence, belonging and visibility that so often accompany descriptions of her practice fail as descriptive paradigms through which to consider the significance of her work. In the case of the Whitworth, the question of visibility is always paralleled by another: visible to whom? What are the racialised dimensions of both looking and seeing, and perhaps most importantly, whose gaze (institutional and interpersonal) has the power to destroy, mutilate and deem a person insignificant? What one sees when they look at Walker’s work, depends, invariably, on who they are.

Radical aesthetics, the philosopher Marina Griznic writes, should seek to ‘expose the sensorial life of capitalism’s momentum’. Despite what the discourses surrounding Walker’s work would have us believe, the revelatory potential of her practice lay not in the exposure of subjects, but in the exposure of the structures that produce them as subjects, a revelation of the mechanisms through which hierarchies of value become attached to human beings. If drawing is a labour of love for Walker, a meditative, highly specialised account of people, places and communities – an attempt to create a ‘positive image’ – she is at her best when this practice bifurcates the force of race, gender and capital. When she turns her attention toward the material consequences of a subject’s visibility in the social world.

In her series Louder Than Words (2009), she sketches landscapes directly onto her son’s ‘Stop and Search’ receipts issued by West Midlands police, and draws portraits of her son on newspaper cuttings reporting the execution of Brazilian worker Charles De Menezes by police at a busy London Underground station in the wake of the 7/7 bombings. Here she uses methods of collaging, overpainting and obscuring to convey the interconnected nature of police violence across time and space. On average, Black people in the United Kingdom are nine times more likely to be stopped and searched than their white counterparts. Louder Than Words is less about the subject and more about the world the subject is forced to inhabit. Walker recognises that her son could be De Menezes, simply in the ‘wrong’ place at the ‘wrong’ time. This act of layering adds critical weight; suddenly the impermanence conveyed by her pencil disappears, having rendered a structuring force.

This series continues Walker’s interest in the social world her subjects must navigate, an interest which differs from the representational dimensions of ‘visibility’, a desire for them to be seen by authorities, institutions and their white counterparts. Such an approach offers the potential for critical analysis, with the recognition of a far more complex conundrum: Walker does not want her son to be ‘visible’ to state authorities, just as the parents of De Menezes did not, yet she cannot separate her own depiction of him from the way the state continually forces him to account for his presence and his right to roam in a classed and racialised structure. In layering an act of love on top of a record of violence, she finally manages to convey what it means to exist as a Black person in a world that wants you dead.

The descriptive paradigms surrounding a work can often obscure its power. The drawings on display at the Whitworth make it clear that both the state and the artist are slippery, imperfect conduits for the production of persons; they cannot account for a human being in their entirety. Just as the state’s processes of bureaucratic documentation leave many quietly erased, so Walker’s depiction of them also fails at telling the whole story. This is why visibility is not a robust enough metric to counter the many dimensions of a violent world. An acknowledgement of this principle, embedded beneath the surface in Walker’s work and clear in her focus on the state and policing, requires us to do more than simply celebrate ‘being here’.

Barbara Walker: Being Here is at the Whitworth, Manchester, until 26 January 2025

Lola Olufemi is a writer and researcher. She is the author of Feminism Interrupted: Disrupting Power (Pluto Press, 2020) and Experiments in Imagining Otherwise (Hajar Press, 2021)