The recent weaponisation of ‘universality’ in the debate reveals that the old colonial lie of European exceptionalism is alive and well

In 2002 the directors of 18 ‘major’ museums of art, cultural heritage and natural history, including the Louvre and the Berlin State Museums, signed a declaration on ‘the importance and value of universal museums’. In essence it was an argument against the restitution of their collections. ‘The international museum community shares the conviction that illegal traffic in archaeological, artistic, and ethnic objects must be firmly discouraged,’ it begins. ‘We should, however, recognize that objects acquired in earlier times must be viewed in the light of different sensitivities and values, reflective of that earlier era. The objects and monumental works that were installed decades and even centuries ago in museums throughout Europe and America were acquired under conditions that are not comparable with current ones.’

Despite receiving robust criticism in the two decades since, its core concepts – that times of imperial war booty are long past, and museums are now ‘agents in the development of culture’ – continue to echo throughout the UK museum sector. A mere year on from this declaration, images of the looting of the Iraq National Museum during the US-led (and Britain-backed) invasion were televised. And as for being an agent of culture, a 2017 Arts Council England report found that 73 percent of the sector felt Brexit had negatively impacted their ability to bring artists and organisations to the UK. ‘There are no foreigners here – the museum is a world country,’ declared Hartwig Fischer, the German director of the British Museum (which was not a party to the declaration), in a 2018 interview with The Guardian. Such statements have often been used against the restitution of objects; an attitude that says, ‘we keep human heritage safe, so that you get to enjoy access to it’.

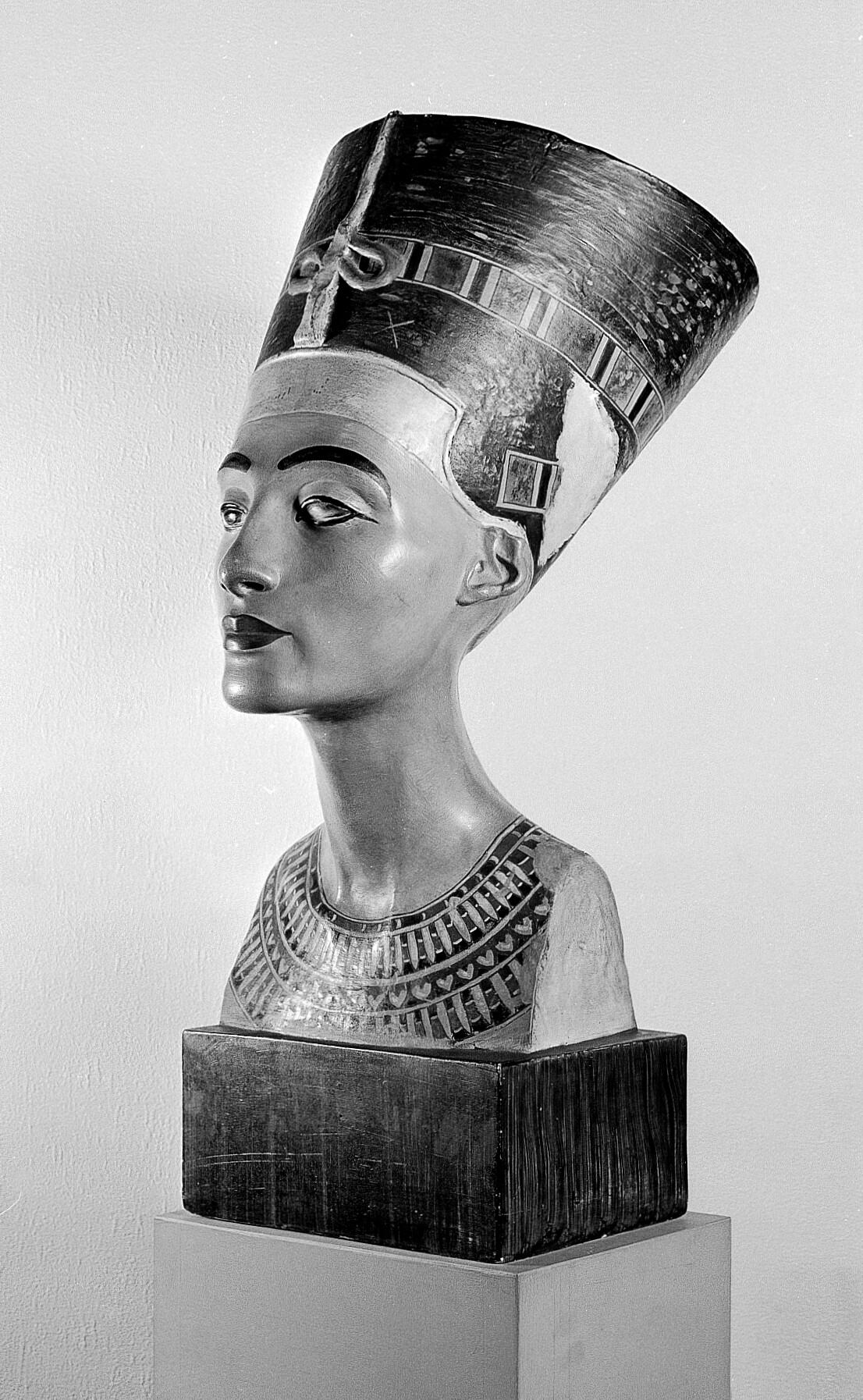

Underlying this is the notion that the safety net of ‘good management’ and ‘cultural stewardship’ has a geography that is firmly rooted within institutions in Europe and North America. Which is to say, universal-mindedness and objectivity belong to a certain place and race. The vast majority of the world, restitution-denouncers will tell us, is floundering in a pit of emotionality, state-sanctioned corruption and ignorance. In other words: those of us not from the ‘universal’ place and race cannot be trusted to preserve our own heritage, and must instead view it under close surveillance, in someone else’s house.

The myth of universalism (à la Fischer’s ‘the museum is a world country’) is nothing new. As Shimrit Lee explains in her book Decolonize Museums (2022), it is a ‘weapon that has been loaded and reloaded across time’ so as to present as seemingly inevitable that the majority of the world’s people do not have the will, resources, intelligence or ability to preserve the things they have created, and a small minority of other people in the global North do. The result is a political narrative (safe West, unsafe rest) presented as though a fact of nature (that’s ‘just how things are’ in ‘those’ kinds of places) rather than what it actually is: a historically traceable outcome of the resource theft and inequitable structures left in colonialism’s wake.

Repatriation – bringing someone or something back to its environment of origin – could see an uptick thanks to the UK 2022 Charities Act. This act allows museums to deaccession objects ‘where there is a compelling moral obligation to do so’, easing some of the roadblocks implemented in the 1963 British Museum Act and the 1983 National Heritage Act. Some, like Glasgow City Council, have begun the process of returning items to India, Nigeria and the Lakota communities in the US. But in October 2022 the UK government delayed the act. ‘It’s possible they hold it back indefinitely because they don’t like the consequences of the change,’ Alexander Herman, director of the UK Institute of Art and Law, was quoted saying in one report at the time.

This act could turn a new leaf for those UK arts institutions and city councils, like Glasgow, that have the will to pursue repatriation efforts. However, it will likely not compel much action from UK museums that hold most of the colonial spoils. These, like the British Museum and the V&A, continue to enjoy exemptions granted by favourable legislation – like the aforementioned 1963 act – once implemented by the British government precisely as a guard against the repatriation claims they anticipated after the string of independences across 1960s Africa. The V&A are an ‘exempt charity’ not regulated by the Charity Commission, and British Museum repatriations remain at the discretion of trustees, most of whom are appointed by the Prime Minister and one by the sovereign. For all their boasts of being ‘world museums’, they sure are well-fortified against having to accommodate the wishes of most of the world.

This stalemate can continue indefinitely so long as the bigger picture remains unchanged: the taken-for-granted projection that repatriation is a clash between the dispassionate, ‘universal’ laws of the West, and the hot-headed demands of the rest. In other words, when faced with repatriation demands, the heritage sector of the global North reverts to its tactical colonialist roots: act as though the colonised ‘lost’ their objects to people who ‘objectively’ handle them better.

V&A director Tristram Hunt has argued that ‘once something enters the museum, it can’t leave’, as if museum legislation is an act of God rather than an inheritance of colonial governance. In a similar vein, historian Jeff Fynn-Paul wrote a 2020 article for The Spectator that stated the genocide of Native Americans ‘does not stand up to scrutiny’ (56 million were killed over a century). The article was subtitled, ‘what should the Europeans have done with the New World?’ – as if invasion and loot are an inevitability, and it flies in the face of common sense to contemplate otherwise. This appeal to (self-designated) universality is just the more palatable face of imperialist chest-thumping. This universalist’s passive voice – objects ‘enter’ museums of their own accord, the ‘New World’ invites its own looting by being there – propagates the idea that no other morality exists but the kind Europe and North America used to justify their past exploits.

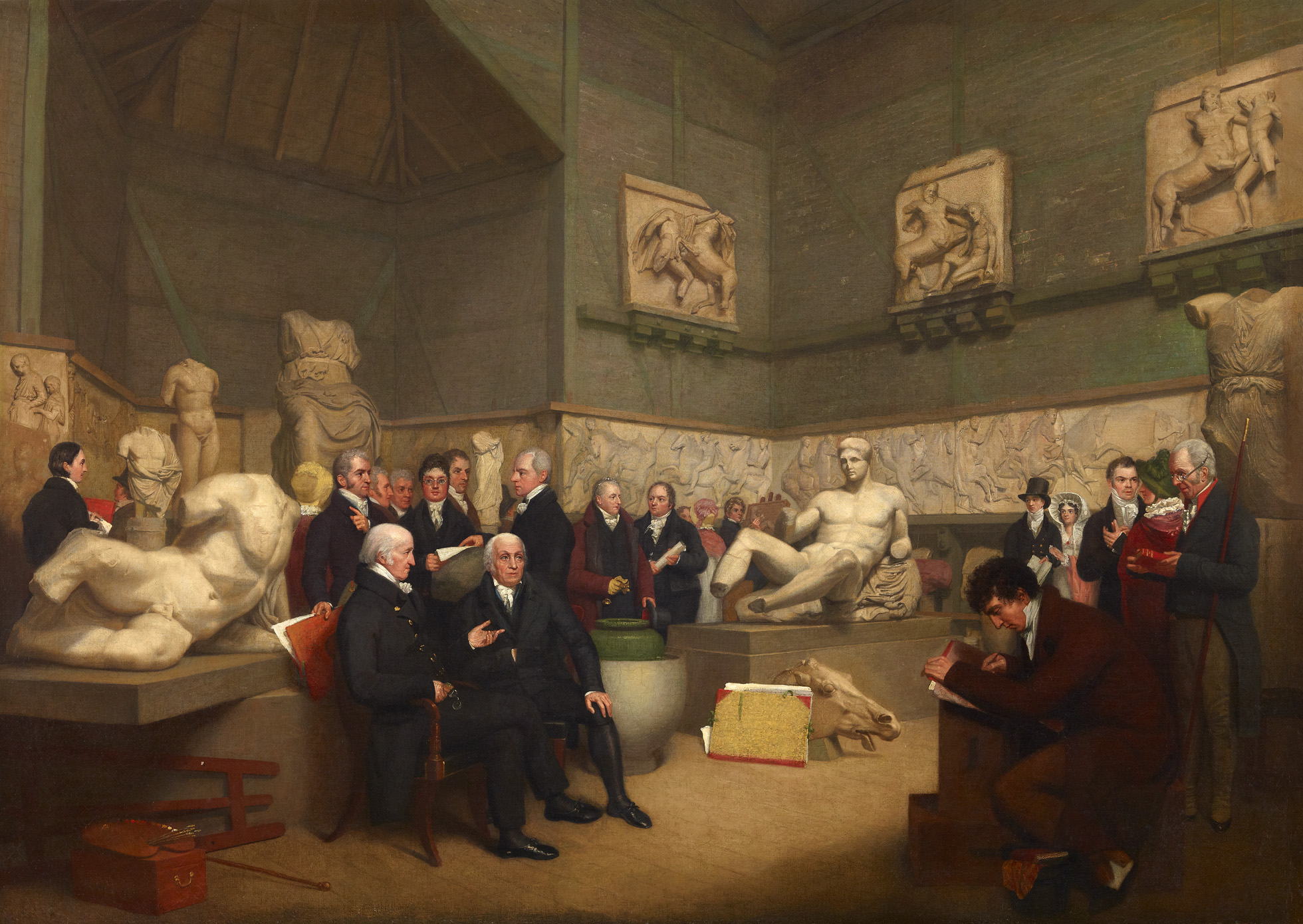

From the nineteenth until the late twentieth century, the cultural production of colonised peoples were degraded as primitive, while being coveted as personal trophies, bloodshed memorabilia, and sold as art in London or Paris. Anthropologists and archaeologists circled the globe to dig up graves and buy bones from dealers, displaying these in pseudo-scientific exhibitions to ‘educate’ people into believing there existed ‘backward races’ from a different species origin. Non-European humans were gawked at in ‘colonial villages’ and at public dissections, helping to shape some of the earliest public exhibition spaces. Their storyline of evolutionary ascent towards the white European man as the logical apex of human history was propagandised for Western imperial domination of the globe. These are the thoroughly flawed ‘universal truths’ at the founding of museums as institutions, and the premises upon which their pedagogical claims rest.

Repatriating objects alone does not challenge the foundations of this house. A broader restitution must occur alongside it: that is, confronting and dismantling a narrative that has outlived the official end of colonialism. That narrative says demands for justice must be subordinated to ‘universal-mindedness’, handed down from the above history as a characteristic apparently exclusive to Euro-American museums, laws and persons.

Mainstream institutions continue to flip-flop on account of being unable to shake this ingrained narrative. The British Museum’s 2019 Inspired by the East show, for example, presented Orientalist art as a mere ‘cultural exchange between East and West’, not only missing the point of Edward Said’s 1978 book Orientalism but also casting Muslims as ‘side characters to the complex lives of the protagonists, white people’, wrote Sumaya Kassim, a researcher and former cocurator at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, in an essay responding to the show. The Museum der Kulturen Basel’s 2012–16 show Expeditions, jovially subtitled ‘The World in a Suitcase’, presented 540 objects originating from Cameroon to Indonesia as innocent memorabilia ‘found’ on nineteenth-century ‘expeditions’. The world is your oyster, European explorer! Left unmentioned is the license to loot, which would have made such long and dangerous trips worthwhile.

On the opposite end are encouraging examples from some museums of restitutive practices, such as democratic decision-making, community-led curating, independent funding and decentring settler/colonial perspectives. Some initiatives of differing scales include Michigan’s Ziibiwing Center of Anishinaabe Culture & Lifeways, whose work extends to protecting tribal intellectual/spiritual property and ceremonially reburying ancestral remains; the Palestinian Museum in Birzeit, West Bank, which has involved the diaspora in exhibition curating; and the rural Nambya community museum in Zimbabwe, which is collecting and recording the oral traditions of the Nambya language, almost stamped out by colonialism. To emulate such practices in postimperial centres like London and Paris – under the relentless scrutiny of corporate art sponsorships, museum–state relations and board members’ financial interests – seems more difficult to achieve. Museum boards may also expect a curatorial programme that aligns with their worldview (at the time of a 2020 Arts Council England report, only 10 percent of chief executives were not white), meaning change-making curators can face institutional resistance.

The pushback against such restitutive work will be even stronger than that against repatriation. Decolonisation, by its very definition, does not align with the profit motive that drove colonisation. But that is precisely why thinking in terms of restitution (dismantle and reconstitute) rather than just repatriation (return) will be crucial if museological practice is to amount to something more than repeating colonial discourses in a glossier guise. In the words of archaeologist Dan Hicks, ‘“give it back and it will only be stolen” is the universal motto of the thief’. Let objects keep being returned, by all means, but in the full knowledge that justice must well exceed repatriation.