To mark the opening of M+, Hong Kong’s new museum of visual culture, ArtReview will select highlights from the museum’s collection as part of its ‘Work of the Week’ series. Stay tuned for a weekly focus on the background story of a single work and the network of associations it conjures

At my family home in Sydney, you’ll find a Buddhist shrine sitting beside a framed illustration of Jesus. Venture into the next room and you’ll spot Chinese calligraphy scrolls, next to a sequined artwork of golden Mandalay spires. Growing up, this eclectic polytheism felt completely natural. But gradually, confusion set in. My mother chastised me for identifying as Burmese; my scripture teacher introduced the phrase false idols; I lost my ability to joke in rapid-fire Mandarin. The house became a mysterious amalgamation of memory, each fragment offering clues to lives that were erased and disrupted.

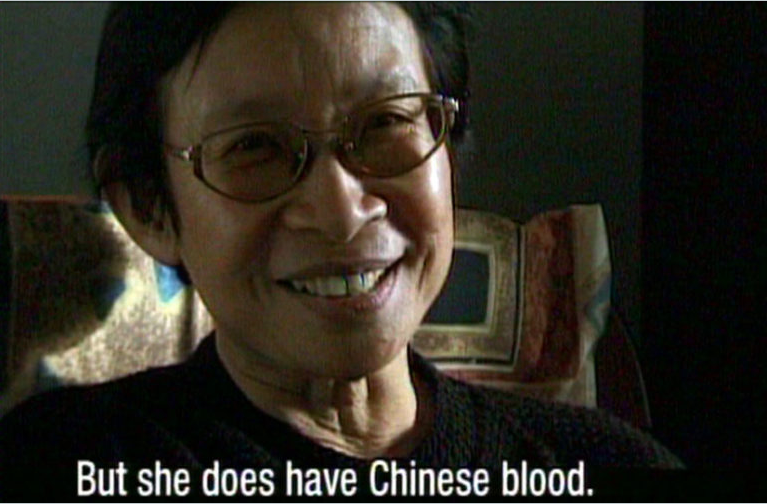

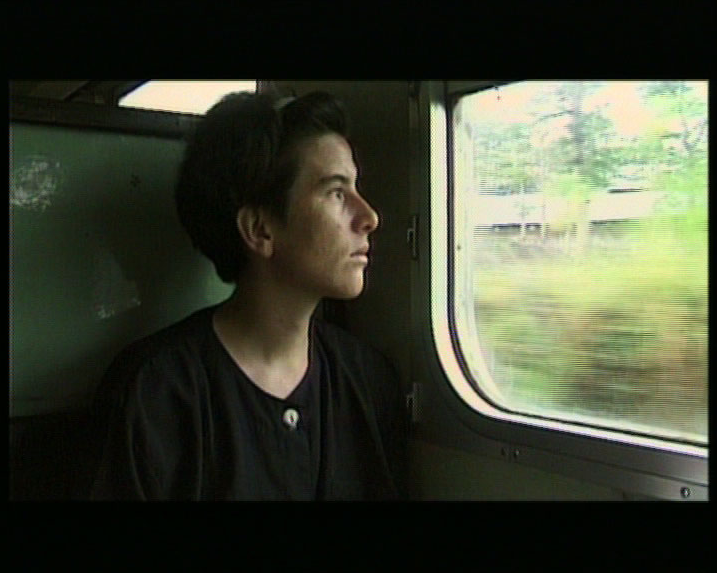

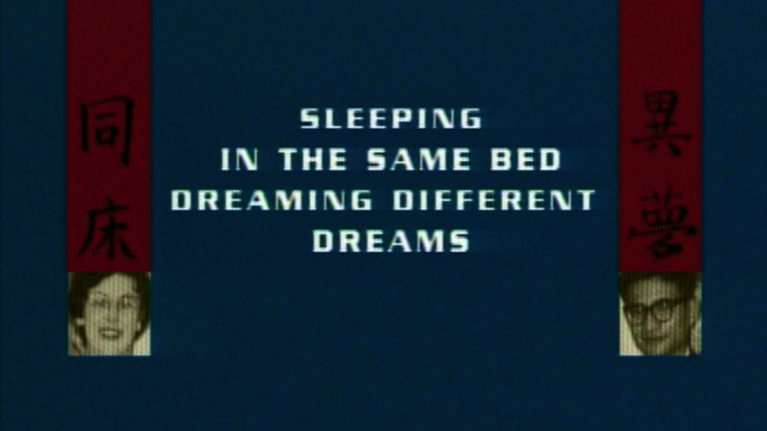

Fiona Tan’s 1997 documentary May You Live in Interesting Times speaks to this ambiguity, opening with an act of naming. Her Chinese-Indonesian extended family stare straight into the camera, as Tan’s voiceover translates their names to English: prosperous tranquillity, faithful and virtuous. The footage then shifts to close-ups of Tan and her siblings: brave strong wood, golden clouds, golden rain. There’s an immediate visual contrast – Tan and her siblings have a Scottish-Australian mother, and the tight close-ups highlight their difference. For Tan, her biracial background and many migrations mean that “self-definition seems an impossibility, an identity defined by what it is not”. Her name beguiles rather than affirms, yoking her to a long history of displacement.

What does it mean to be Chinese? Known for her auto-fictional visual art, Tan investigates this question through observational cinema verité techniques that acknowledge the presence of the camera and Tan herself. As she embarks on a globe-trotting journey to interview family members, Tan takes interest in each locale’s aesthetic markers. She fixates on wet markets in Hong Kong, contortionists in Beijing, dancing monkeys in Java. There’s a voyeuristic quality too, in Tan’s observations of close family: the camera lingers over her uncle’s cupping session and her father’s late-night tai chi. A Lunar New Year celebration – something I associate with joy – is rendered in a frenzied montage of detonating firecrackers and violent flashes of red.

The othering of these elements creates a disconnect between the filmmaker and her subject, a fraught position Tan acknowledges. The most striking segments of the film feature her active presence, which emphasise feelings of disjunction. In one scene, a Chinese hairdresser states that Tan can’t be Chinese “because of her nose”. Meanwhile, at a family gathering, Tan utilises a long take to capture her siblings’ discomfort as they try to define their Chineseness. When her brother finally states: “I’d like to regard myself as a citizen of the world,” the siblings all laugh, sensing the wry inadequacy of the answer. If cultural markers are framed with distance, these family scenes are always intimate, as Tan discovers that the paradoxes in her own identity are mirrored in almost everyone she talks to. “It started off as a search,” Tan intones, “now I feel I’m constantly in search of my search.”

Ethnically Chinese but brought up in Indonesia, the Tan family spread across the globe due to anti-Communist persecution in the 1960s. Most members are reluctant to “look back” – one aunt, now based in Cologne, asserts: “You concentrate on what is and what will be.” But Tan, whose life is marked by fragmentation, searches for meaning in personal accounts, regional maps, home videos and archival footage – building a choral portrait of how culture is complicated by trauma. Often this is achieved through the anachronistic use of footage that collapses the barriers of space-time: a scene where Tan’s mother haltingly recounts fleeing Indonesia is interspersed with flashes of the unrest (fire, hanging, corpses) and Tan’s father mowing the lawn (mundane, stoic, at a distance). An aunt and uncle, who have remained in Indonesia, state they “wish to be true Indonesians” after long being denied citizenship – all while carrying on Chinese traditions. Their migration has resulted in a fusion of rituals, habits and spirituality; the couple attends church while speaking to their ancestors through their living room shrine. “I don’t not follow any region’s rituals,” her uncle states, “I have my own ritual”.

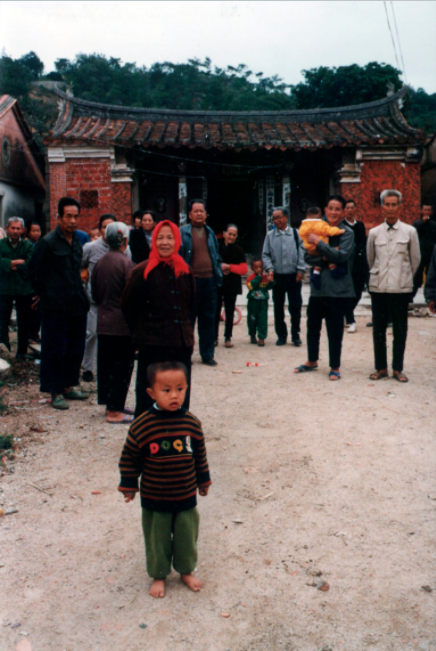

Tan’s journey ultimately takes her all the way to Shan Hou, the 400-year-old village from which her family originated. In a revelatory beat, she realises that all members of the village are related to her. Many of them were born in Indonesia, just like her, and returned to live at their ancestral seat. The delight of some villagers in meeting her is juxtaposed with those who remain in the background, staring blankly – even in this moment of wonder there is alienation. Tan’s act of discovery does not generate a greater sense of wholeness; instead, it sensitively reveals the non-essentialist nature of identity. Though Tan does not find belonging in China, she comes to an understanding of the parallel desires of her family, and the way loss echoes through generations.

When I first visited Myanmar, I discovered my cousins spoke no Mandarin or English. My Burmese was paltry, so we developed a complicated system of gesturing to make each other laugh. I sent my sister a photo of the street where my mother was born and raised, an entire adolescence in which she never received full citizenship. A few years later, my sister visited our Yeye’s decaying ancestral home in Taishan, where he lived before Japanese invasion. I received an image of my great-grandfather’s portrait; his dark eyes, staring through a tunnel of time, were exactly like my brother’s. Perhaps this is what identity is – an imperfect assemblage of echoes, illuminating the ways in which we are disparate but inextricably bound.

Fiona Tan’s May You Live in Interesting Times (1997) can be played on demand in the Mediatheque at M+, Hong Kong