A new project sees artist-designed flags hoisted globally, but whom do these symbols serve?

On a pole sticking out from a building in downtown São Paulo a new flag has been hoisted. Its design is familiar, taking the basic structure of the Verde e amarela, Brazil’s national flag.Yet in this version, the outer colour is black for liberation, not green, the colour of the Portuguese court; the rhombus is red for spilt blood and radicalism, not the yellow of the House of Habsburg; the floating disc, peppered with stars, green for the Amazon and its indigenous owners, not the blue of the original. The flag is by artist Bruno Baptistelli, part of a series by various artists that have been flown from Galeria Jaqueline Martins, as the gallery itself is closed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Baptistelli’s work is the latest in an ongoing project titled Four Flags by Amsterdam-based curators Julia Mullié and Nick Terra that started in the Dutch capital before spreading to São Paulo, Lisbon and Bogotá and will continue to Chicago and Dusseldorf. Dozens of artists have so far taken part. For a week in April – from a private house in Amsterdam’s Jordaan neighbourhood – a white flag by Evelyn Taocheng Wang, on which the words ‘Breathing normal and that’s crazy enough’ (a reference to the major symptom of COVID-19) were written, was flown; another, by Laure Prouvost, featured a still from the artist’s 2017 film Dit Learn, in which the line ‘Let’s start again’ overlays an image of the artist, masked and pleading.

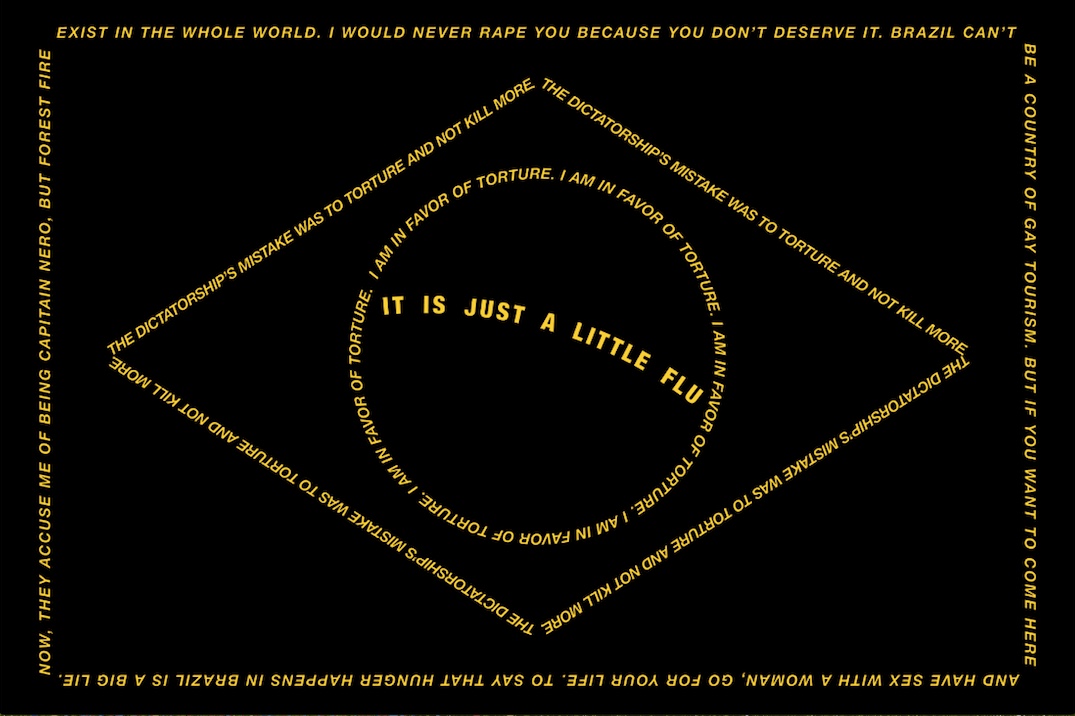

While Prouvost’s work suggests the pandemic might offer an opportunity to remake society for the better, in Brazil there is no such tentative optimism. Perhaps because the COVID-19 pandemic has only further demonstrated the autocratic tendencies of the country’s leadership, many of the designs have been emphatically political. André Parente also took the basic structure of the country’s national flag, the composite shapes delineated by quotes from President Bolsonaro, the rhombus formed through the repetition of the line ‘The dictatorship’s mistake was to torture and not kill more’, the circle ‘I am in favour of torture’. Instead of the motto Ordem e Progresso, Parente inserts Bolsonaro’s latest insanity, his violent dismissal of the COVID-19 threat as ‘It is just a little flu’. As well as understating the risk of the disease, Jair Bolsonaro has repeatedly violated social distancing laws and encouraged tightly packed rallies attended by his fans, a support base that though diminished is no less fervent in their fascistic vitriol.

Parente and Baptistelli’s appropriation of the national design comes at a time when Bolsonarista rallies are typified by a sea of yellow and green regalia (and as the country edges towards yet another political crisis, perhaps even a coup). The Brazilian flag was once popular across society, not least as a symbol of the country’s football prowess, but is now exclusively embraced by the far right (on a night out in São Paulo last year, I was picked up on for the faux pas of wearing green and yellow). If Parente’s work illustrates the rhetoric that now engulfs the symbol, then Baptistelli’s work proposes an alternative, perhaps even a new start. The design is an allusion to David Hammons’ vexillographic artwork from 1990, African-American Flag, in which the artist merged the Stars and Stripes with the Pan-African flag as a symbol of the Black Liberation struggle (which, mirroring the Four Flags project, was first made for the Black USA exhibition at Amsterdam’s Museum Overholland). Likewise, the Brazilian artist’s design has been made in response to the increasing violence directed towards black Brazilians from state forces.

As Baptistelli’s flag flew in São Paulo on Sunday, demonstrators gathered to mark the death of João Pedro Matos Pinto in São Gonçalo, Rio state, shot by police when they burst in on a friend’s home in the Salgueiro favela. The 14-year-old was just the latest in a long line of cop killings: 177 people dead in April in that state alone, 1,814 last year. Of course most of those passing under the flagpole outside the São Paulo gallery will know this already – for some, racism will be a lived reality every day. This week, another political scandal: the man heading up the government foundation charged with promoting Afro-Brazilian culture referred to black activists as ‘bums’ and ‘bloody scum’ in a leaked recording.

A staggering 97 percent of Brazilians believe that their country is racist. Yet state killings, in which the victims are disproportionately black, largely pass by with relatively muted public outrage. Earlier this year I reported on several vigils held for nine young black people, killed after a police raid in the south of São Paulo: they were moving, heartfelt occasions, but the numbers gathered were tiny, with none of the coverage afforded to the protests we’ve seen this week in the US. As activist Bruno Rico points out in a recent article titled ‘Why Black Lives Matter protests haven’t taken off in Brazil’, this is partly because the country has a very different history of racial politics, but it may also be sadly due to the sheer ubiquity of the killings. Baptistelli’s work should be a banner for action: international as well as local. Flags have long symbolised ownership over lands, a tool of colonialism and oppression; Bapistelli, as Hammons did before him, subverts this to create a symbol for a people that must be heard.