‘Literature’ sounds reactionary, but might that change if it can take some cues from the dynamics of art shows?

I have this feeling that everyone dislikes literature. Not reading and not writing, both of those are practices that many people enjoy; but somehow when these two come together they form literature, and then everyone dislikes it. I wonder why this is. I know that I want so much from this word literature. I want it to do so much work, whereas it mainly seems to do no work at all. It sounds dour and demented in a way that art doesn’t. Art sounds bright and fizzing and susceptible to anything new. Literature doesn’t. Literature sounds reactionary.

Maybe the better word for what I want is just writing and I should abandon literature as a word. If you plug literature into some game of word association, what would first come into my head is a line by Paul Verlaine that ends his poem ‘Art poétique’ (1874), a poem in which he defines what he wants from poetry, which seems to be music and the refusal of meaning. And then, devastatingly, he concludes: Everything else is literature, which still seems irrefutable in its dismissiveness.

Do I know what I mean by literature, or what I want it ideally to mean? Something to do with language being put under total pressure, maybe. But also something to do with time, and with this relationship of writing and reading. Literature depends on the idea of a work, and I don’t think the process of writing/reading can be understood without the idea of a work, but at the same time maybe what I find difficult is the idea that the book must be the only support for literature, the only kind of work.

Of the many charming moments that occur in the published conversations between the artist Philippe Parreno and the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, there are two lines from Philippe that I’ve always liked in particular: 1. ‘I like meta-stories, stories of stories. Is an object always the end of something? Does everything really always start with a scenario and end with an object?’ And 2. ‘To me, it’s exciting when the content overflows beyond the form or the other way round. It’s the irresolution that is interesting.’ It’s that refusal of the object, that fascination with the overflow and the unresolved, which preoccupies and delights me. When I try to think about literature in the same kind of way, I wonder if what fascinates me is that really Philippe is always working in another, under- lying, medium. His true medium is time.

One of the first things I ever saw by Philippe was his video Marilyn (2012), with its AI voiceover of Marilyn Monroe’s voice and algorithmic reproduction of her handwriting. Later I discovered the drawings In Preparation of Marilyn: ‘The Quasi Living’ (2013), which are the records of this handwriting, on Waldorf Astoria paper. But also there’s the long withdrawing shot at the end of the movie itself, where the camera moves back and back to open the viewer out onto the fact of a filmset. In other words, in Marilyn and the works around Marilyn you can easily see how a work might be in a state of both pre- and postproduction: a work is one possible pause in a constant process of thinking.

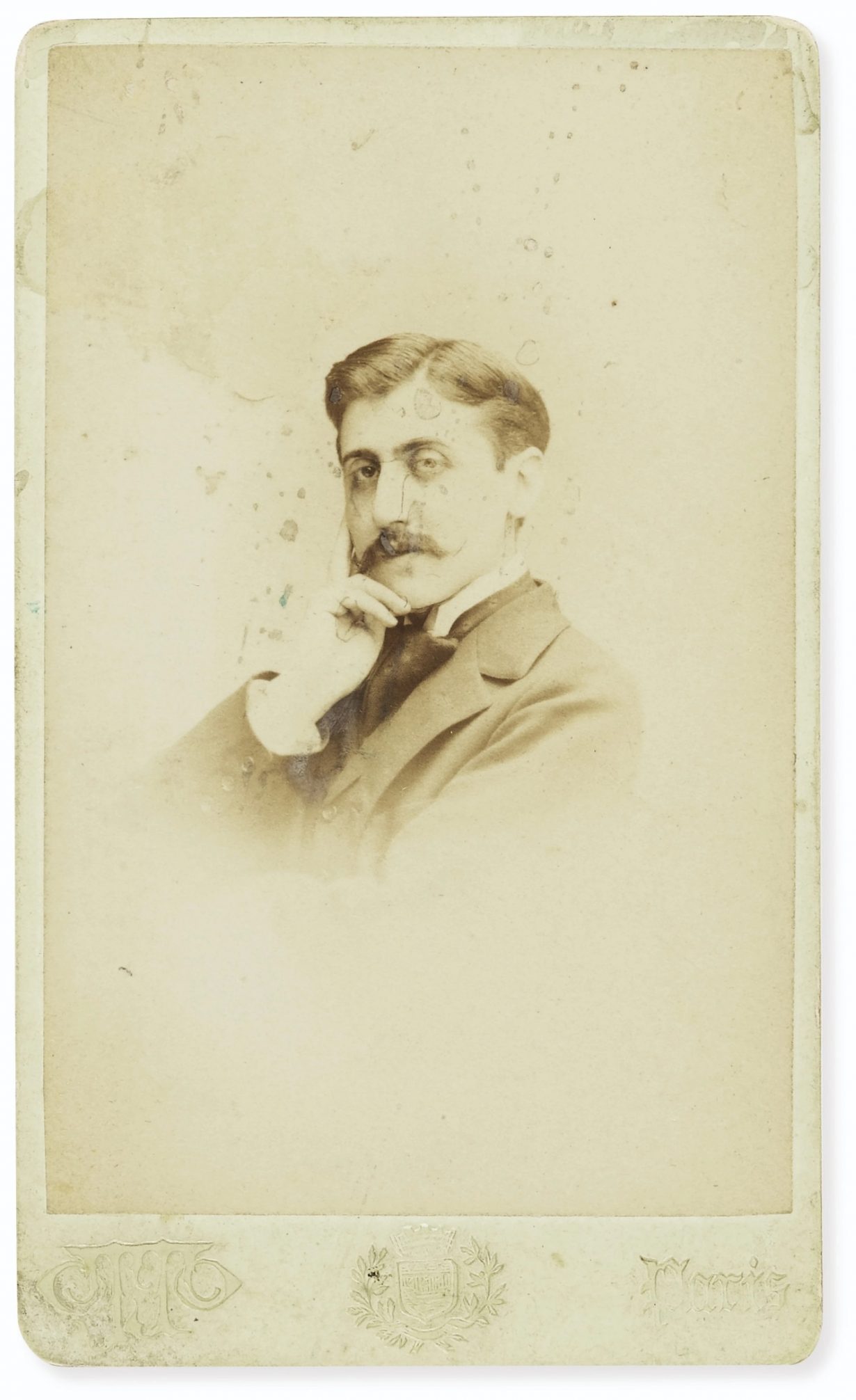

Is this how I want a work to be when I use this word ‘literature’? I think it must be! Because as soon as the definition of a work is made more fluid, it’s exciting to observe how quickly other definitions unravel. If a work isn’t the only aim, then a certain relaxation can occur about a work’s construction: it can be collaborative in the making, or participatory in the viewing, which- ever definition you prefer. Instead of one person talking and another person being silent, there can be something a little closer, at least, to a conversation – something like what Marcel Proust once proposed in his definition of ‘this calm and pure friendship which is reading’.

Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu (1913–27) is of course the great novel of time. It’s always said that this novel is about memory, whereas it might be more accurate to say that it’s about forgetting, an absolute forgetting. Time fractures all things: memories, love affairs, selves… Everyone is multiple, and a name conceals an infinite succession of identities. But what most excites me is the way, in order to be true to this intuition, Proust changed the way a novel addressed its reader: by the simple mechanism of its giant length. Normal novels, you realise, are far too fast. Proust managed to construct a book whose theme is time and memory, and whose form becomes an exercise in time and memory for its reader. The novel becomes literal, as if it becomes an installation or show. The reader of this novel is forced into slowness, and into forgetting. Characters change names, or appearance, or status. They reappear and disappear. They are part of a pattern that is too large to be completely apprehended.

Make a book a show, in other words. That’s what I want literature to do. Which also correspondingly then means: why not make a show as literature?