Adriano Pedrosa’s Foreigners Everywhere wants art to speak for everyone, but it’s hard to know what it might actually say

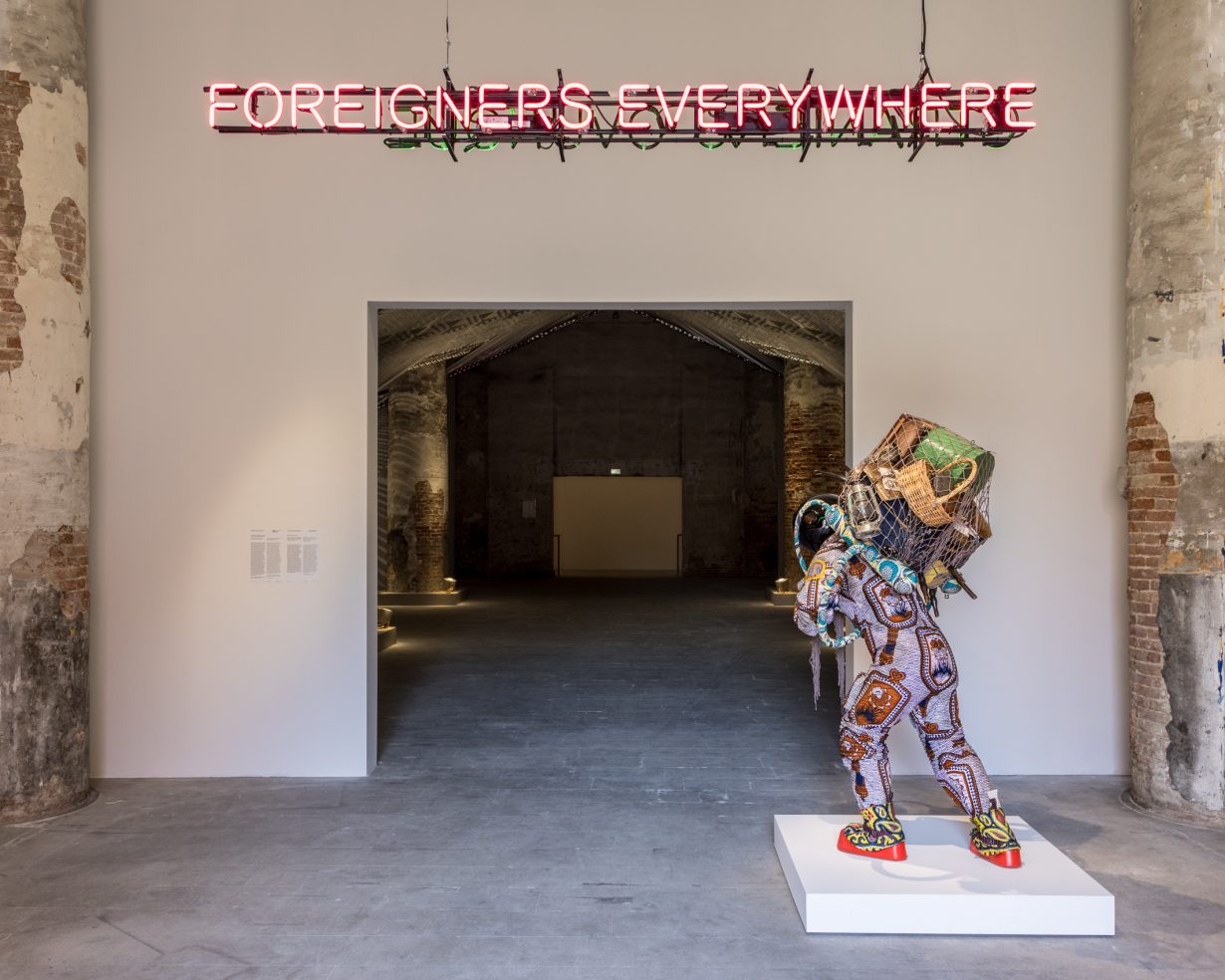

‘Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent,’ wrote the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. I get something of that old twentieth-century European immigrant’s thought facing Foreigners Everywhere, curator Adriano Pedrosa’s exhibition for this year’s Venice Biennale. Trumpeted as the Biennale’s first curator from South America, Pedrosa’s sprawling exhibition sets up multiple versions of the foreigner, or ‘stranger’: stranger to the place of Venice and the institution of the Biennale, seen as European, Western, probably white. But stranger, too, in the sense of those historically perceived as ‘strange’ by Western societies. So Foreigners Everywhere bundles together works from artists of the Global South, the art of Indigenous people, the work of queer artists, of folk artists and of work by artists falling within that still-contentious description of ‘outsider’ art. And it furthermore splits the show in half, between presentations of contemporary work and a large number of twentieth-century paintings – the ‘Nucleo Storico’ sections – which focus on ‘global modernisms and modernisms of the Global South’. Of these three sections, two are salon-hang style rooms of abstract art and of portraiture (in the International Pavilion venue in the Giardini); the third, in the Arsenale – which borrows the glass display panel system designed by Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi for São Paolo’s MASP, where Pedrosa is director – presents paintings by artists who left Italy for foreign lands during the last century. Migration and the stories of migrants feature prominently. Who, in the face of such plurality, could possibly write anything about it?

For Pedrosa, it’s clear what the political stakes are, the show’s rhetoric reflecting the kind of benign cosmopolitanism that preoccupies many liberal curators and art institutions currently. ‘Wherever you go and wherever you are you will always encounter foreigners – they/we are everywhere,’ Pedrosa writes, adding that ‘no matter where you find yourself, you are always truly, and deep down inside, a foreigner’. This doesn’t quite ring true, of course – most of us would prefer a home to exile, with others who share some common bond – and it reveals the limitations of a curatorial politics that, by seeking to give a platform to marginalised and minoritarian subjects everywhere, at Venice Biennale as the supposed ‘centre’ of the artworld, can only ever really make symbolic gestures of acknowledgement and recognition. The political situations of the groups recognised in Pedrosa’s show are not changed by Foreigners Everywhere, because those situations are not susceptible to mere sympathy and gestures of artistic inclusion. It would be a narrow-minded philistine who was not interested in and open to seeing how other people articulated their own perspective on the world, the form of their own difficulties and troubles, through artworks. But here one arrives at the limits of the ethical version of representation in art shows. It’s ethically good that everyone is represented, but what is there otherwise to say about the art? Who is it for, and who does it address?

It’s perhaps why, in the contemporary work, Foreigners Everywhere presents a series of video documentary and video essay, works which straddle social reportage, activist documentation and critical interrogation. In the Arsenale is Marco Scotini’s ongoing Disobedience Archive (2005–), a circular enclosure of around 40 monitors, a collection of videos spanning decades that link migration, postcolonial and diaspora politics, and global LGBTQ+ movements. Elsewhere there are the stories of lesbian couples facing the social and cultural difficulties of raising their own children in Singapore, in Charmaine Poh’s videos. Fred Kuwornu’s We Were Here (2024) essays the history of the representation of Black Africans in European culture since the Renaissance, in a style verging on TV documentary. Looming in the cavernous space of the Arsenale are the multiple hanging video projection screens of Bouchra Khalili’s The Mapping Journey Project (2008–11); each screen a different story told by the person whose hand we see drawing on a map of Europe and the Middle East and North Africa, tracing their routes – from Morocco, Afghanistan, Somalia and elsewhere – towards and into Europe, as they narrate their experiences: the transit, the waiting for lawyers and immigration papers or visas, the relatives they stay with, the calls to family back home. Austere and precise in its structure, The Mapping Journey Project is exemplary in its use of video as human testimony and acknowledgement; one voice tells us that all they want is to live, to work, to be. Everyone would want that. The trouble is, social and economic power always gets in the way.

These works notwithstanding, what visually dominates Foreigners Everywhere is the preponderance of painting, collage and drawing. It is an oddly comfortable show, for all the rhetoric. The Nucleo Storico galleries present a retold art history of the twentieth century through the two main cultures of modernist painting: realist and social documentary painting and mostly-geometric abstraction. Redistributing the story of twentieth-century modernism has been going on for some time now, and Pedrosa’s selections are made to establish a distributed and diasporic multiplicity to the two great artistic paradigms. Here, they are both evidence of migrations, of artists and ideas, and a metaphor for the virtue assigned in the show to migration, ‘alterity’ and foreignness-within-one’s self.

On the other hand, if these galleries of paintings also, by accident, have echoes of the bric-a-brac and the thrift store, it’s because not all of the paintings, regardless of what life-story and cultural history they are evidence of, are as good as each other. But then again, who can judge? While Foreigners Everywhere makes cultural inclusion and the celebration of distinct identities a priority, in bringing artists together we’re faced with the question of how to look, and what to value, and whether this can be shared. In front of the bright acrylic-on-paper psychedelism of Colombian artist Aycoobo, whose intricate and dazzling paintings elaborate on the worldview of the Nonuya people, a culture whose cosmogeny and origin myths he represents, how do we relate? As a secular atheist, cosmologies and mythologies of every sort have never interested me. What, then, can we speak of? Politics and aesthetics don’t necessarily coincide, nor do ‘we’ all see or speak of the same experiences.

It becomes a question of whether such largescale biennial exhibitions are starting to run out of road, while their thematic preoccupations seem now to run in circles. The last Venice Biennale exhibition, Cecila Alemani’s The Milk of Dreams, touted its majority-female lineup, while Alemani aligned her show with all the current posthuman, ecological thinking, with which ‘artists propose new alliances between species, and worlds inhabited by porous, hybrid, manifold beings’, and who challenge ‘the modern Western vision of the human being − and especially the presumed universal ideal of the white, male “Man of Reason”’. Maybe these are the right ideas to have. Maybe ‘modern’ ideas were really just ‘Western’ ones, or white male ones. The through-line to Foreigners Everywhere, though, is in the absence of any ‘universalising’ approach that might allow us to find what people might have in common, through artworks. Ironically, the ideology of modernism, for its flaws, suggested something of that universalism. Instead, cultural difference tends to become aesthetic indifference. But at a deeper level, Foreigners Everywhere settles on an idea of the global in which, since all global experience is seen only as aspects of displacement, migration or marginality, and in which the idea of nation states is treated with suspicion, no bigger idea of political community emerges. Pedrosa tries to argue in his introduction that Venice is ‘a city whose original population consisted of refugees from Roman cities’. He forgets that in coming together, those refugees went on to forge the Venetian Republic, a city-state which lasted a thousand years. Now it is a charming relic and the global artworld’s playground. Magical thinking about how we are ‘all foreigners’ helps no one, since it denies the realities of what it means to negotiate political differences and make a society in common with others, to become no-longer foreign. Those politics are real, and often profoundly difficult, if not brutal, and cannot be wished away by art shows: during the Biennale’s opening week, Giorgia Meloni, Italy’s rightwing premier, was busy signing accords with the Tunisian president Kais Saied, offering business credit and investment to bolster Tunisia’s control of illegal migration, itself having become a focus for migrants intent on crossing where Italy is to Africa. Foreigners everywhere? At the Biennale, yes. In the real world, not so much.

The 60th Venice Biennale, 20 April – 24 November

This article was amended on 22 April 2024 to reflect the fact that Adriano Pedrosa is the Venice Biennale’s first curator from South America, not the Biennale’s first curator from the Global South