ArtReview sent a questionnaire to artists and curators exhibiting in and curating the various national pavilions of the 2022 Venice Biennale, the responses to which will be published daily in the leadup to and during the Venice Biennale, which runs from 23 April to 27 November.

Firouz FarmanFarmaian is representing the Kyrgyz Republic; the pavilion is at Hyde Space, in the Giudecca Art District.

ArtReview What can you tell us about your exhibition plans for Venice?

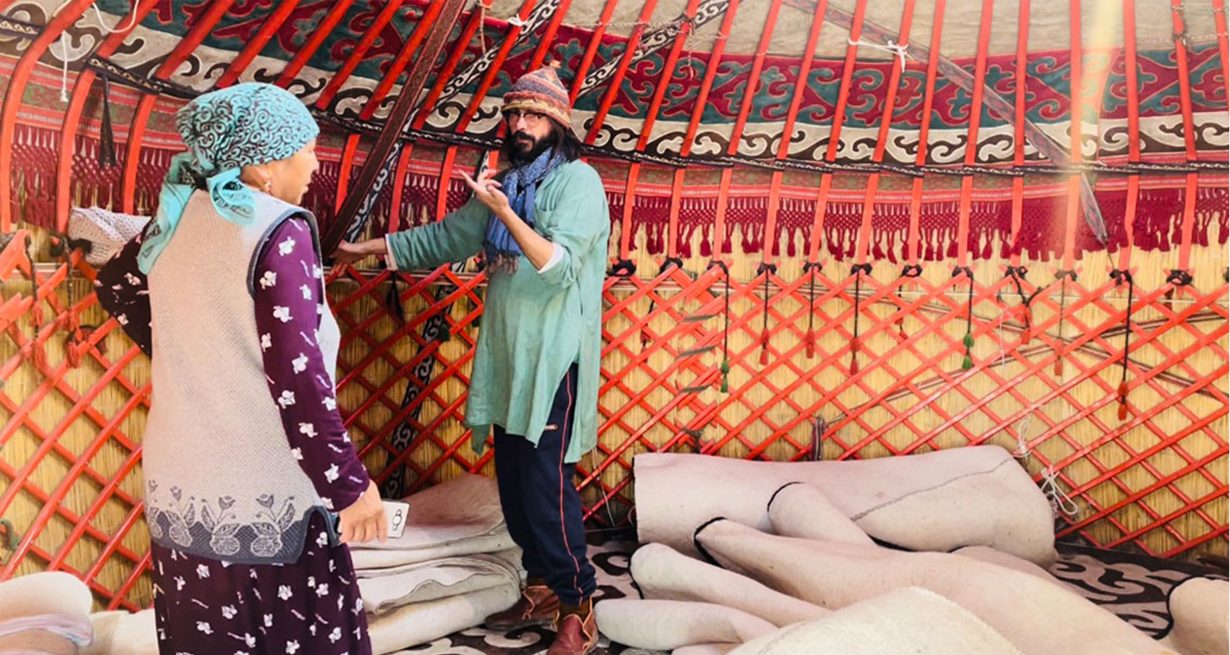

Firouz FarmanFarmaian I set up tent throughout the winter season and developed intense collaborative interactions with local artisans, marking the exhibit as my foundational multivalent post-tribal experience – introducing sourcing of raw wool along with transformative tribal semiology embedded around a constellation of underlying thematics related to immateriality, the sacred and the immemorial role of women in the passage of knowledge.

All these projected aspirations, profound intuitions – empirical and mystical – have been brought to their fullest under the cupola of a partnership crafted with the Ministry of Culture of the Kyrgyz Republic through 18 months of travels, friendship and exchange. The journey plunged my research and practice within the intimate fabric of the nation’s potent nomadic culture, leading to collaborations with craftswomen cooperatives NGO’s (the Altyn Kol handicraft cooperative) that strive to empower women and families up in the Tien Shan range’s Naryn Valley.

The result of my extensive sourcing-production process will honour the Kyrgyz Republic’s first national participation in Venice.

AR Why is the Venice Biennale still important?

FF The Venice Biennale through the 20th century has been an uncommercial endeavour that has given the important movements, the realm of art, and philosophy of art, the space to emerge and find audiences. It’s traditionally been at the forefront. Significant movements like surrealism, or art of the avant-garde came to mainstream acclaim here, including works by artists such as Georges Braque, Marc Chagall, James Ensor and Paul Klee, along with a Pablo Picasso retrospective and the display of Peggy Guggenheim’s personal collection.

That’s the reason we’re doing the biennale because I believe there needs to be a new movement, one which transcends the last forty years of materialistic exploration. As in Zen Buddhism, materialism isn’t all bad, there needs to be an equilibrium. André Malraux famously said, the 21st century will be spiritual or will not. The biennale is central in finding this balance.

AR Do you think there is such a thing as national art? Or is all art universal?

FF The notion of National art is the process of tracing the evolution of art or ideas to a specific culture. At this time in the evolution of man we need to realize that all our identities are layered. These layers have to be respected, and some of them can be called national art, but I believe that a well digested understanding of your own identity opens us up to understanding other identities. It’s not about closing down and putting these identities into silos, it’s about the very opposite of this.

All art is universal by definition, as it is an imprint of a vision which defines a time in the evolution of thought. It documents a moment on earth to create a collective history, one which transcends national identity or time. In that sense, there is nothing more transcendental than art.

Studying tribal cosmogonies led me to the notion of a ‘post-tribal’, which relates to the idea that there is a common archaic sub-vortex which unites us all – one which is preindustrial, almost pre-civilisational.

AR Which other artists from your country have influenced or inspired you?

FF Chingiz Aitmatov, Kyrgyzstan’s most celebrated writer of the 20th century, in his book Ode to the Grand Spirit, illustrated an exchange with a spiritual master which for me embodies the idea that ancient traditions and folklore can be embedded into contemporary culture.

Artistry is intimately linked to craftmanship in Kyrgyz Republic. The artists I met through Altyn Kol, the Women Handicraft Cooperative, are extremely talented multifaceted artists and together through inspirational exchanges, we created the vision and fuelled the drive behind the Gates of Turan project.

AR How does having a pavilion in Venice make a difference to the art scene in your country?

FF The Kyrgyz Republic is deeply rooted in millenary tradition and over the last forty years has been making a studied transition into contemporary culture. The first Kyrgyz Republic Pavilion is a beacon to which all Kyrgyz artists, within and outside of the Kyrgyz Republic, can relate to and build upon for many decades to come. The whole Gates of Turan team, including curator Janet Rady, hope that the process of putting together and presenting this pavilion will bring awareness to the incredible artistry in Kyrgyz, and help to galvanise international funds towards its art scene.

AR If you’ve been to the biennale before, what’s your earliest or best memory from Venice?

FF I’ve not taken part in the biennale before officially… My friend, Italian sculptor Rosella Gilli said something which resonated with me recently: doing the biennale is like passing the baccalaureate in art, you do it once.

AR What else are you looking forward to seeing?

FF I studied architecture for a period, as my grandfather was an official architect in Iran, and I travelled to Venice twice on sketching trips. I have a very positive vision of what Venice represents, being the crossroads of the east and the west for so long. The Silk Road started in The Kyrgyz Republic and ended in Venice, so there is an extremely long tradition of exchanging art and ideas internationally.

I’m also really looking forward to seeing Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan’s exhibition, as well as all those also having their first pavilion like Nepal and Cameroon. I believe Gates of Turan has an affinity with the whole of Cecilia Alemani’s concept of the biennale, The Milk of Dreams, exploring the transient, transformational quality art has between different nations and people.