Each time a digital file is copied to a computer, it mutates – taking on or losing a certain amount of ‘computational dust’. Indeed, for some several-thousand-odd years, there has been talk about whether something is being added or taken away in the relationship between humans and the machines they have produced. Historically, the discussion has ignored the wider context of these machines, how they relate, directly, to race, gender, age or ability – the human experience of production. Detroit-based artist Matthew Angelo Harrison squares this discussion, squeezes and doubles it ad infinitum through his own experience, to create effective distances and proximities for viewers to navigate.

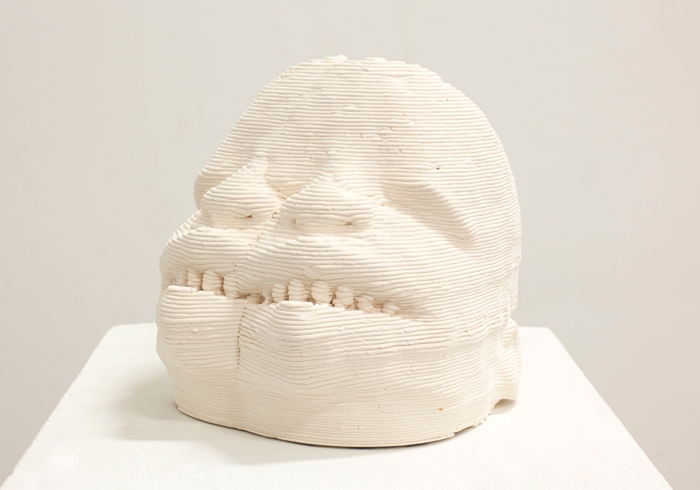

Harrison’s work is produced using 3D-printing machines, which he has made himself, and by other industrial processes that fold in computational information. The 3D printers, which he considers ‘platforms’, are primarily tasked with making copies of wooden African masks in visible layers of ceramic. Printed from digital scans (already copies), using information inputted by Harrison, each iteration has an identity that can’t be confused with its original. As the iterations continue, forced variations (such as compressions or doublings) are added to the information and documented in each mask’s title, magnifying the difference. Like a file that has been copied, opened and saved in another format, they are respectfully tied to their origins but distinctively not the same. The pressure of authenticity is released and an agency takes its place.

This agency is also generously extended to the viewer. By laying bare the 3D printer for what it is, a platform making three-dimensional objects by stacking two-dimensional layers, Harrison lets the viewer into the agency-building process. Viewers can observe its poetry without being disillusioned by it, a rare encounter in the field of technology. In performances where he is present for days or even weeks in the exhibition, he oversees a live version of this building process. The energy that he creates by moving about the space like a surveyor stays with the works even after he has left, as though the objects become memories of their construction. The labour, and who has performed it, is not erased.

The late Suriname-born Dutch artist Stanley Brouwn’s 1970 exhibition Going Through Cosmic Rays at the Abteiberg Museum in Mönchengladbach consisted of exhibition rooms with seemingly nothing in them. Brouwn insisted they were full of cosmic rays visitors had to walk through – an allusion to the tangible possibility of unperceived matter. One of Harrison’s most recent works, SBrwn_1 x 1 x 1bkgd;bkgd (±0.1) (2017), takes on an edition of books by Brouwn as another artefact of meaningful history. When a dimension was needed to determine the length of printed ceramic filament that would layer itself into a box shape to represent the books, he chose the distance from his studio (in central Detroit) to the factory where his mother used to work. This numerical detail has no visibility in the final output but remains as matter sprung from the human desire to construct, from memory, from the movements of the artist. To me, these are Harrison’s cosmic rays.

Cécile B. Evans is an artist based in London and Berlin whose work often incorporates new technologies, including robotics and AI, to explore the effects of the digital world on how we feel. Her video installation What the Heart Wants (2016) was a centrepiece of the last Berlin Biennale

Matthew Angelo Harrison lives and works in Detroit. Recent solo projects include Post Truth / The Lie That Tells the Truth, at Culture Lab, Detroit, and Dark Povera Part 1, Atlanta Contemporary (both 2017). He participated in four group shows in 2017, including The Everywhere Studio (on through 26 February) at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, and Fictions at The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York. Forthcoming exhibitions include I Was Raised on the Internet at Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco, and the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities. Harrison will also show work at the 2018 New Museum Triennial, Songs for Sabotage.

From the January & February 2018 issue of ArtReview, in association with K11 Art Foundation