In a parallel universe, in which Thailand transformed fully from absolute monarchy in 1932 and has maintained a thriving democracy ever since, Siburapha would be a national hero. But the newspaper editor and novelist’s reputation as a pioneer of modern literature, mass communication and print media has in this universe been kept alive only by a small group of intellectuals. The relative neglect of this influential political activist and peerless Thai writer is evidence of the fact that, in our reality at least, Thailand has never existed as a true democracy.

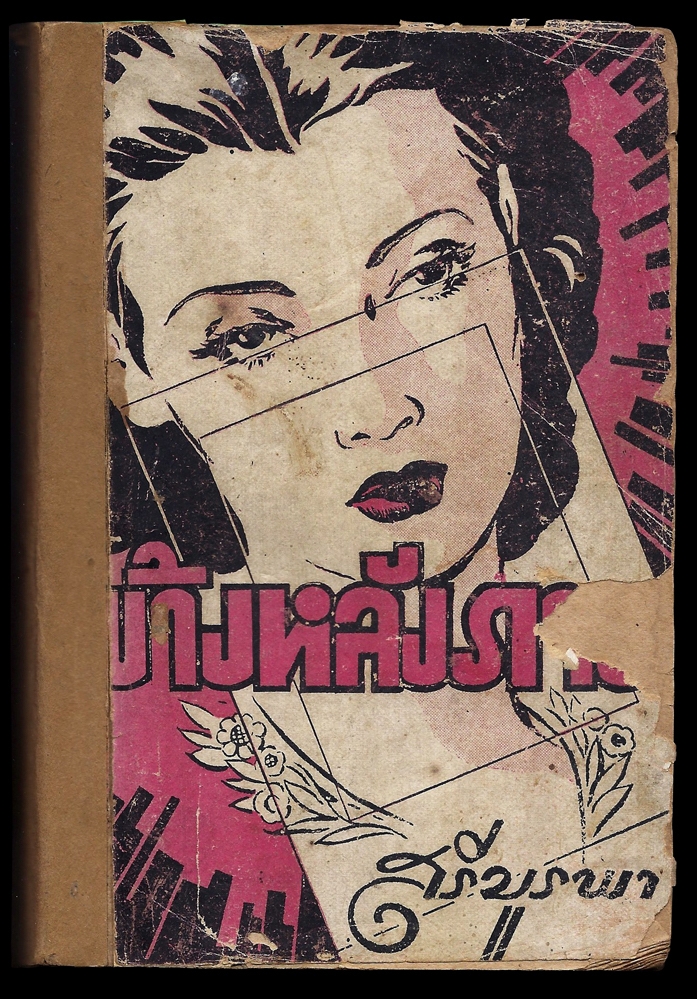

That most Thais do not realise the influence of Kulap Saipradit (who used the nom de plume Siburapha) on their society and culture might partly be due to the fact that, in order to escape imprisonment after a coup, he went into exile in China in 1958 and passed away there in 1974. With most of his books now out of print, this advocate for human rights and democracy is best remembered by the general public for a single novel, Khang lang phap (translated as Behind the Painting in 1990).

It is no surprise that Behind the Painting (written in 1937 and serialised in a newspaper before its publication as a book), the story of a romance across generations and social classes, appeals to a wider readership than Siburapha’s more explicitly political works, such as the outspoken Lae Pai Kang Na (Looking into the Future, 1957). Most of the key scenes take place in the faraway and evocative land of Japan (in Siburapha’s era, only people of high social status, or those who received special work or educational opportunities, travelled abroad), and the novel is filled with sumptuous passages and poignant dialogue.

The novel’s tragic heroine is Lady Kirati, a beautiful royal who agrees to marry the older Chao Khun Athikanbodi because, at thirty five, she fears that her chances of finding love have passed. On honeymoon in Japan, she meets and falls in love with Nopporn, a twenty-two-year-old Thai student asked by Chao Khun to accompany Lady Kirati on some of her outings. The star-crossed lovers nearly die of heartbreak when she boards her ship to return home, but by the time Nopporn has completed his studies, the passion he once felt has been extinguished. He returns to Thailand and marries, unaware that Lady Kirati is still in love with him until she sends a message from her deathbed. Her confession may be Thai literature’s best-known scene, familiar even to those who have never read Behind the Painting.

Siburapha’s progressive convictions manifest in his characters’ points of view more than in the style or structure of his stories. Lady Kirati embodies a person whose worldview is informed by her interest in art: she is a Sunday painter who finds in art some freedom from the monotony of life as a woman in an upper-class family. Proof of her and Nopporn’s past love comes in the form of a watercolour she paints depicting a shared moment on a mountain near Tokyo, and the memory ‘behind the painting’ keeps her love alive.

Beyond its romantic appeal, Behind the Painting is also a recommended ‘outside-reading’ book at many high schools and has been made into TV series, plays (including a musical in 2008) and films (in 1985 by director Piak Poster, and in 2001 by Cherd Songsri). The novel has therefore been able to stake its claim as a literary classic in mainstream Thai culture, detached from its author’s politics and even from other of his works that delve more deeply into social issues. While the issue of class in the novel has been the subject of some discussion, it is rarely treated as social critique in the same way as Siburapha’s Pa Nai Cheewit (Forest in Life), also serialised in 1937. The latter is another story of doomed love, but its protagonist is a young soldier who, after a coup, is imprisoned on a charge of treason (the novel wasn’t published in book form until 15 years after the author’s death).

The enduring popularity of Behind the Painting might also be attributable to the fact that its success was welcomed even by intellectuals who held opposing political views but acknowledged Siburapha’s literary talent. Because the calls for equality and scathing social critique were more muted than elsewhere, conservative scholars were able to express their admiration for the author of a classic romance without having to dive into the other dimensions of his work.

The latest artistic tribute paid to Behind the Painting is the multimedia installation Museum of Kirati by Chulayarnnon Siriphol, which was on view at Bangkok City Gallery from last November to this January. Museum of Kirati builds on, and plays with, Siburapha’s tale of lovers from different classes, and the lasting beauty of their memories. The installation is set up as a fictional memorial to Lady Kirati’s love, created by Nopporn, and includes a 50-minute film in which Siriphol plays both Nopporn and Lady Kirati. Tracking the novel’s plot, it alternates between live-action sequences shot as a contemporary low-budget underground film and animation sequences, all interspersed with lines from the book. The drawings used in the animation scenes are framed and hung on the walls to each side of the screen.

On the rear wall – ‘behind’ the screen showing the film, which is titled Behind the Painting (2013) – seven large portraits in baroque gold frames loom over viewers. Both the frames and the pictures within them are in fact projected images of Lady Kirati, Nopporn and Chao Khun as played by Siriphol. These pictures wobble slightly (Siriphol calls them ‘non-still pictures’), and if you gaze at them long enough, you will see that the images seem eventually to be scorched and burned. Beside them is a 43cm-tall bronze statue of Lady Kirati seated on a chair; an oil portrait of her painted on a ceramic pin with a gold setting; and a neon light shaped into the English phrase ‘Forget Me Not’, a snatch of dialogue from Chert Songsi’s film. A ‘Kirati Memorial Book’ has also been printed, compiling imaginary posthumous messages to Lady Kirati from her father, friends and Nopporn.

The ongoing project, which stretches back to the making of the film in 2013, mixes the creation of a fictional world with film, sculpture, portraiture and performance art (for the opening and closing of the exhibition, Siriphol played host in the role of Nopporn). Siriphol has said he may continue the project, meaning that this may not be the final chapter in his take on the memories of Lady Kirati’s love.

In the artist’s statement for Behind the Painting, Siriphol wrote that Lady Kirati symbolises noble life prior to the regime change in 1932, blessed in every way but ‘bereft of the freedom to live life’, whereas Nopporn represents the ‘middle class that would be the key force driving the country in the future’. The act of continuing to imagine the story between the two in the present is ‘to combine the soul of the leading class with the body of the bourgeoisie that does the moving’ in order to maintain Lady Kirati’s world. Or, to put it another way, the middle class embodies customs and traditions, and in doing so moves them into the future. The process preserves the old world instead of dismantling it, as would be predicted by historical materialism and its postulates that the interaction between classes (in the Thai context, between those of ‘royal blood’ and commoners such as Nopporn) leads inevitably to conflict.

Museum of Kirati invites comparisons with Marcel Duchamp, both because of Siriphol’s cross-dressing (which blurs the line between ironic humour and earnestness) and in the concept of creating a fictitious museum that stipulates that art is born of experience rather than of a material object. But while Duchamp’s work challenged traditional art practices and ideas in search of the new, Siriphol’s Museum of Kirati raises questions about the transition between eras in Thailand, even if the installation’s half-facetious and ambiguous message does not entirely shed the novel’s reputation as a popular romance.

In this universe, Siburapha’s writing will continue to be a rich source of information and inspiration for anyone seeking to understand modern Thailand. Many of his observations remain valid in a context that has changed too little over the intervening decades. That we have an artist like Siriphol taking up Siburapha’s work, and using his own vision to move it beyond itself, reminds us that there is much more to this great writer than the purely romantic aspects of Behind the Painting for which he is now best known. Still, I can’t help but wonder: which of Siburapha’s works would be most celebrated in that parallel universe?

From the Spring 2018 issue of ArtReview Asia