The sinister elements of ‘defensive architecture’ hide in plain sight, disappearing into the weft of our city fabric. They are ambiguous technologies, both in terms of their sources and their intended effects. Such security measures go well beyond the public-safety guidelines mandated via building codes and infrastructural regulations. Whereas these are meant to guarantee safe inhabitation, ‘unpleasant’ or ‘unkind’ architecture is designed to keep people away, or to prevent modes of use that are considered unappealing. Code is intended to protect people from architecture. In an alarming inversion, defensive architecture defends architecture against the problem of people.

And just as buildings appear to offer public amenities, such as benches and open space, developers and designers are increasingly devising ways to make the use of these feel uncomfortable. Many defensive techniques operate just above the threshold of illegality, creating sensations for the user that – while unpleasant – do not cause lasting bodily harm. This is often achieved through furniture and ironmongery. Most urbanites are, by now, familiar with the subdivided benches that prevent lying down, or metal knobs and ‘pig’s ear’ rails intended to make skateboarding impossible. Other devices make use of landscape, such as berms and ha-has, or thorny shrubs that overhang railings and low walls to discourage sitting. A third category mimics dysfunctional automation: sprinklers that soak public areas at random intervals, or the ‘mosquito’, a device that repels teenagers by emitting a high-frequency noise inaudible to older adults.

And whereas code is imposed by the state, many of the newer defensive techniques are rolled out privately, in order to control the access to, and uses of, facilities in urban settings. This distinction is likely obscured by the ongoing deployment of physical security measures by state, regional and city-level authorities simultaneously. If visible, the seizure of common spaces by private parties could be contested through public scrutiny and outcry. In the emotionally charged atmosphere of an ongoing ‘war on terror’, however, the imposition of restricted access to public spaces has also been enabled by the belief that such security measures benefit everyone. This idea carries yet more weight in the era of smaller, more localised terror attacks – which may occur at the supermarket as much as at grand, symbolic targets. At the same time, social-media posts have fuelled controversy over physical measures such as the ‘anti-homeless spikes’ implanted to prevent rough sleeping on pavements in front of London’s banks and businesses. Likewise the notorious Camden Bench, a Zaha Hadid-esque sarcophagus designed to discourage almost any form of use.

These technologies, and their broader climates of social control, are explored in two exhibitions in Singapore: The Substation’s Discipline the City (ongoing) and Jason Wee’s Labyrinths at Yavuz Gallery (recently ended). The former, cocurated by the institution’s artistic director, Alan Oei, and me, is an attempt to study the defensive culture that permeates multiple social spheres, in diverse – and often contradictory – ways. Some works explore boundaries of spatial delimitation, such as Chen Sai Hua Kuan’s Something Nothing (2017), a white enclosure without corners or edges that leaves viewers unable to gauge depth or height. Others imagine the opposite – the worlds of behaviour or experience that become possible when the rationality of the city is ignored. In Taiwanese artist Kuang-Yu Tsui’s videoworks, for example, public spaces become the backdrop for bowling, foot massage and vomiting. At the same time, Oei and I attempted to see the architecture of the Substation building itself as an instance of control. To emphasise the complicity of the gallery, the building’s usual access was blocked, with a new path knocked through the walls for visitors to traverse the exhibition spaces. Architectural technologies such as the maze and the trapdoor offered curatorial subjects as well, as provocations for participating artists.

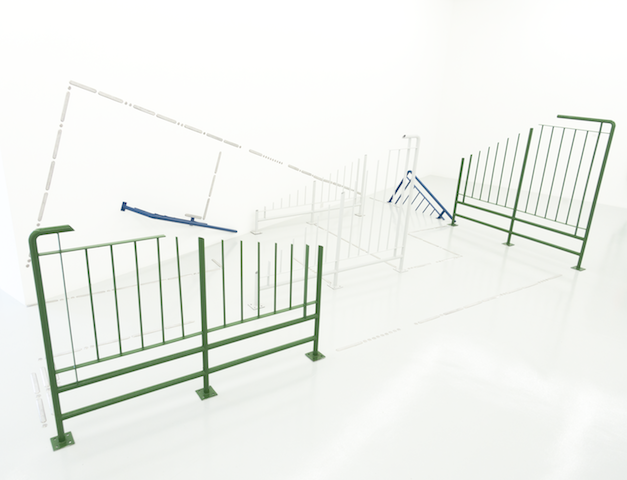

Jason Wee’s recent work is similarly interested in the materiality of architectural control. In Labyrinths, the artist created a variable motif from the crowd-control barriers and chickenwire grids used to manage public events in Singapore, such as the LGBT-friendly Pink Dot festival, and the queue for Lee Kuan Yew’s lying in state in March 2015. Wee manipulates the form of these, slicing and rearranging them in juxtaposition with other symbolic and physical elements. In one setting, the metal barricades are placed against the architectural notation for a property line, creating a relationship between abstraction and the physical enforcement of limitation and prohibition. Another work, Living Rooms (2017), overlays barriers against the ubiquitous ornamental window screens of older Southeast Asian buildings – in order, perhaps, to underline the similarity between modern security and the charming, ‘homely’ defensive elements of yesteryear. Wee appears to recognise the defensive in the deep code of the familiar; discipline and control have, he suggests, been an intimate part our cities for a very long time.

From the Winter 2017 issue of ArtReview Asia