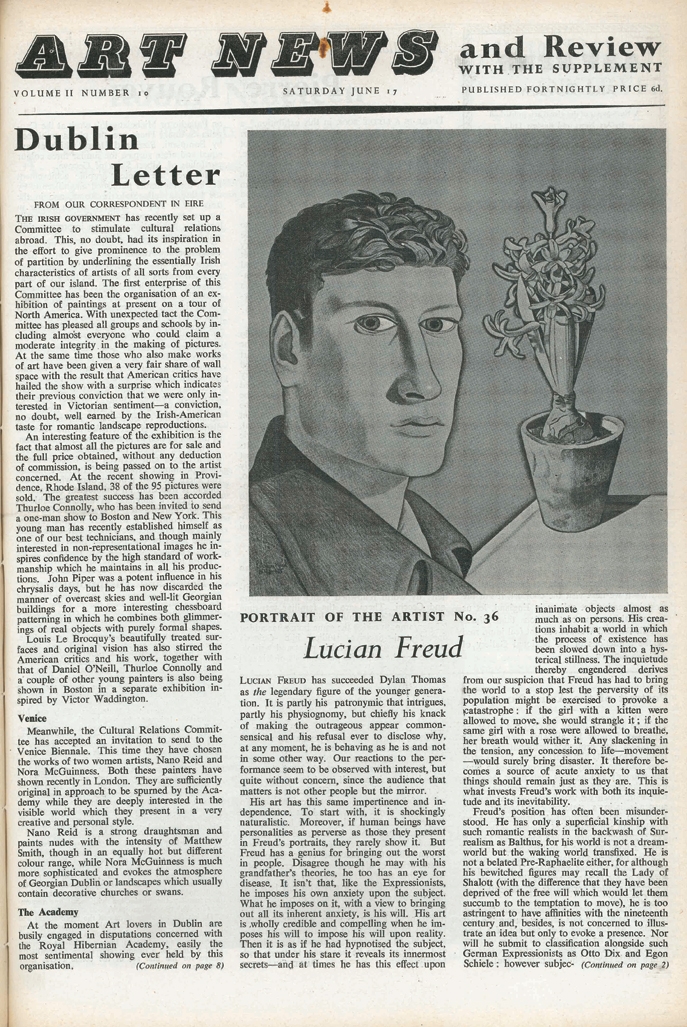

Portrait of the Artist No 36: Lucian Freud

Lucian Freud has succeeded Dylan Thomas as the legendary figure of the younger generation. It is partly his patronymic that intrigues, partly his physiognomy, but chiefly his knack of making the outrageous appear commonsensical and his refusal ever to disclose why. Our reactions to the performance seem to be observed with interest, but quite without concern, since the audience that matters is not other people but the mirror.

His art has the same impertinence and independence. To start with, it is shockingly naturalistic. Moreover, if human beings have personalities as perverse as those they present in Freud’s portraits, they rarely show it. But Freud has a genius for bringing out the worst in people. Disagree though he may with his grandfather’s theories, he too has an eye for disease. It isn’t that, like the Expressionists, he imposes his own anxiety up on the subject. What he imposes on it, with a view to bringing out all its inherent anxiety, is his will. His art is wholly credible and compelling when he imposes his will to impose his will upon reality. Then it is as if he had hypnotised the subject, so that under his stare it reveals its innermost secrets – and at times he has this effect upon inanimate objects almost as much as on persons.

His creatures inhabit a world in which the process of existence has been slowed down into a hysterical stillness. The inquietude thereby engendered derives from our suspicion that Freud has had to bring the world to a stop lest the perversity of its population might be exercised to provoke a catastrophe: if the girl with a kitten were allowed to move, she would strangle it; if the same girl with a rose were allowed to breathe, her breath would wither it. Any slackening in the tension, any concession to life – movement – would surely bring disaster. It therefore becomes a source of acute anxiety to us that things should remain just as they are. This is what invests Freud’s work with both its inquietude and its inevitability.

Freud’s position has often been misunderstood. He has only a superficial kinship with such romantic realists in the backwash of Surrealism as Balthus, for his world is not a dreamworld but the waking world transfixed. He is not a belated Pre-Raphaelite either, for although his bewitched figures may recall the Lady of Shalott (with the difference that they have been deprived of the free will which would let then succumb to the temptation to move), he is too astringent to have affinities with the nineteenth century, and besides, is not concerned to illustrate an idea but only to evoke a presence.

Nor will he submit to classification alongside such German Expressionists as Otto Dix and Egon Schiele: however subjectively he may see things, he does not vaunt his subjective feelings by allowing them to twist the object into grotesque deformations. It is tempting to relate him to Rousseau, for his early work had the gawky monumentality of a Sunday painter’s and he uses meticulous detail to much the same effect as the Douanier: the slowness with which his world has been assembled suspends it in a state of enchantment. But Rousseau as a portraitist, being the most humble and self-effacing of painters, is the Sunday afternoon photographer concealing himself under a hood to take a picture of his friends, whereas Freud is the haughty magician casting a spell on a nervous volunteer. The true precursors of his hypnotic and meticulous art are the more sinister portraitists of sixteenth century Germany.

Freud has, I believe, produced easily the best portraits painted in this country during the last decade. All the same, they are not of a type that a man can go on painting all his life without parodying himself: they are too concerned with a simple facet of human nature. During the last year or so he has tried to open his eyes to the more normal aspects of personality: he has been less anxious to mesmerise, more ready to absorb. At the same time, his style has softened and become more atmospheric. This has deprived his work, as well it might to start with, of most of its intensity. Of the three wholly successful works in his recent exhibition, two (the Portrait of a Woman and the etching Girl in Bed), while they belong to his latest period in technique, belong in spirit to an earlier period.

The third, however, is an achievement of an altogether different order from that, characteristic of his work up to the end of 1948, which this article has tried to define. This is the small painting of a girl with fair hair and bare shoulders, entitled simply Portrait. With its fresh, cool unsentimental lyricism, it has the mood of a love poem by Auden. Whereas Freud’s past portraits of beautiful women have revealed, as unerringly as Baudelaire, what is evil in them, here he has come to terms with beauty.

From the 17 June 1950 issue of ArtReview (then titled Art News and Review)