Presented across six exhibition spaces along the waterways of the Gadigal, Barramatagal and Cabrogal people, the Biennale of Sydney returns with rīvus – a sprawling investigation into our relationship with the natural world. Taking rivers, wetlands and other salt and freshwater ecosystems as its framework, the 23rd Biennale of Sydney seeks to position humans in dialogue with non-human entities (whether these be aqueous beings, fossils, mountains, trees, oysters, or particles of energy). In this way rīvus presents itself as its own living and breathing ecosystem: an entanglement of voices and perspectives.

the team at Eveleigh Works). Photo: Document Photography. Courtesy the artist

Indigenous peoples have long understood non-human beings to be deserving of protection and care, and many of the standout works in this biennale attend to First Nation histories, knowledges and connections to land and water. At the entrance to the Cutaway – a below-ground concrete venue partially open to the outdoors – sits Barkandji artist Badger Bates’ glinting steel sculpture of the Ngatsi (rainbow serpent). Associated with the creation of the Barka (Darling River), ariver now suffering after years of extractive industry exploitation, Bates’ sculpture is both an avowal of country and a plea to save its waterways.

At the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Marjetica Potrč has collaborated with Wiradjuri Elder Uncle Ray Woods to weave together the stories of two rivers similarly threatened with ecological destruction. Potrč and Woods’s bold depictions of abundant worlds filled with streams, trees, birds and people (whether painted on paper or directly onto the gallery wall) speak to the life, rights, and histories of the Galari (Lachlan River) in Western New South Wales and the Soča River in Ljubljana, Slovenia. In the upstairs gallery, Abel Rodríguez (Mogaje Guihu) translates his knowledge as ‘a namer of the plants’ into a set of meticulous and transfixing studies of the Amazon (such as Ciclo anual de los árboles de la maloca (Annual cycle of the trees surrounding the Maloca), 2009, a series of wall-mounted drawings).

Indeed, many of the works across the biennale reiterate the ways in which Western-centric notions of the ‘environment’ (a word that gained currency during the industrial revolution for ‘that which surrounds us’) have warped our understanding of the world.As the writer Amitav Ghosh argued in a recent interview with The Guardian, our current ecological crisis is explicitly linked to a Western history built on capital and empire: ‘Why has this crisis come about?… Because for two centuries, European colonists tore across the world, viewing nature and land as something inert to be conquered and consumed without limits’. Given, as anthropologist Jason Hickel has suggested, the disproportionate effects of unchecked global heating are akin to ‘atmospheric colonisation’, and given that, in Australia, Indigenous claims to country are so readily dismissed by mining companies and government, it is somewhat surprising that the prevailing feeling of rīvus is one of quiet contemplation, instead of a call to act.

Much of this has to do with the Biennale’s conceptual framework, rather than the vibrancy of the works themselves. As the curators suggests in their exhibition text, rīvus revolves around questions that centre on non-human entities: ‘Will oysters grow teeth in aquatic revenge? What do the eels think? Are the swamp oracles speaking in tongues?’ Indeed, several of the biennale’s ‘participants’ are those other than human beings (a 365-million-year old fish fossil is displayed at the MCA). At the entrance to every venue is a vertical screen displaying the ‘voice’ of a river. That is, an Indigenous custodian or a person involved in the river’s protection who speaks to the audience on its behalf. At Barangaroo, for example, a representative of the Atrato River in Columbia narrates how its waters and surrounds were granted legal personhood in 2016 – a landmark court decision upholding the river’s right to protection, conservation and restoration.

The placement of each of these river voices suggests that any visitor to the biennale invariably occupies the position of listener, which then invites a follow up question: What is it they choose to hear? Does the experience of the biennale necessitate ‘a fundamental shift’ in our responsibilities towards non-human entities, as is so claimed, or does a visitor simply fall back into passive reflection – an empathetic spectator of mass extinction and biodiversity loss, but an impotent one, nevertheless?

Or, to go a step further, is it possible to meaningfully engage with these concerns via the blockbuster event that is a biennale, given it is an institution which brings with it its own ecosystem: board-members, sponsors, patrons and benefactors. Indeed, absent from rīvus is an acknowledgement that Australia is the biggest global exporter of coal, and that fossil fuel companies often seek to sanitise their image by sponsoring and supporting just these kinds of art events.

installation, 1 hour 32 min (installation view at Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, 2016). Photo: Luc Boegly. © the artists

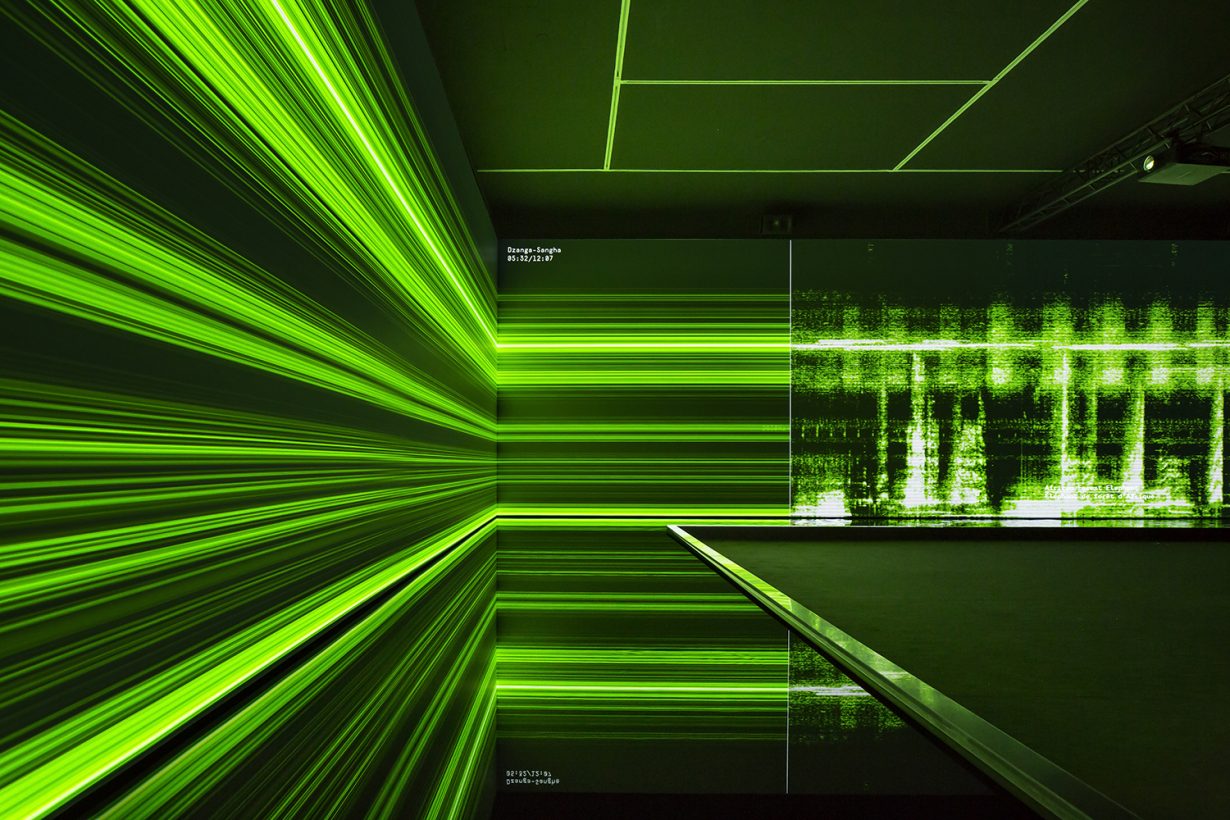

When the biennale opened in March, it did so in the same week as unprecedented rainfall drenched Australia’s entire Eastern seaboard. Whole towns were swallowed when rivers broke through banks and levies. Many are still without housing or adequate support, and Sydney has already experienced its annual rainfall in the first three months of the year. At the time I viewed Bernie Krause and United Visual Artist’s collaborative installation, The Great Animal Orchestra, a soundscape of 15,000 animal calls housed in a marquee at Barangaroo, the roof buckled under the weight of the wind. The sound of heavy rain competed with the audio of Krause’s field recordings. Elsewhere, mould started to appear on the installations in semi-open spaces, and water rushed down the Cutaway’s sandstone wall, pooling on the concrete floor. Nature, it seemed, was making its own intervention.

For a biennale wishing to elevate the voices of non-human entities, it is perhaps fitting that it is these natural forces – not representations of them – that give rīvus its urgency.

23rd Biennale of Sydney: rīvus, various venues, Sydney, closes 13 June