In her latest solo show, the young Nuremberg-based artist Iulia Nistor explores the uncertainty and disorientation of the wanderer, who allows herself to be led aimlessly through space, encountering objects and elements along her way that have stories to tell, narratives to be imagined. And it is exactly these imagined narratives, and later more generally the realm of possibility, that also inform Nistor’s approach in titling her exhibition as if offering four different options of interpretation.

The show is in two parts, spread between the two floors of the gallery and divided stylistically but loosely connected conceptually. The two rooms of the ground floor each contain a single installation featuring a painting, a wall drawing made of tape and an artist book. The large paintings are nebulous constructions that play with perspective and empty space by juxtaposing recognisable forms with abstractions and seemingly randomly placed everyday objects (a book, wrapping paper, etc), painted from a bird’s-eye view. The wall drawings in the corner extend onto the floor through a series of connected lines and dots, and resemble constellations in three dimensions.

The artist books reveal the concept behind this puzzle: Nistor chose some points on her paintings from reproductions of the work, which were then transferred through vellum paper onto a photocopy of a page in a book lying around in her studio. The text of the page was taped over, so that only the words corresponding to the points remained visible. These points were also marked as yellow dots on the vellum, then connected by lines, and the resulting form was recreated as the wall drawing mentioned above. The titles of these two works (i. primind cadere Ochiul acum sprijina alta se-nvirteste intre and ii. primind cadere Ochiul acum sprijina intre se-nvirteste alta, both 2014) result from four possible ways of reading those words in groupings that are both nonsensical and poetic, undermining the dictatorship in meaning-construction that a specific title would engender.

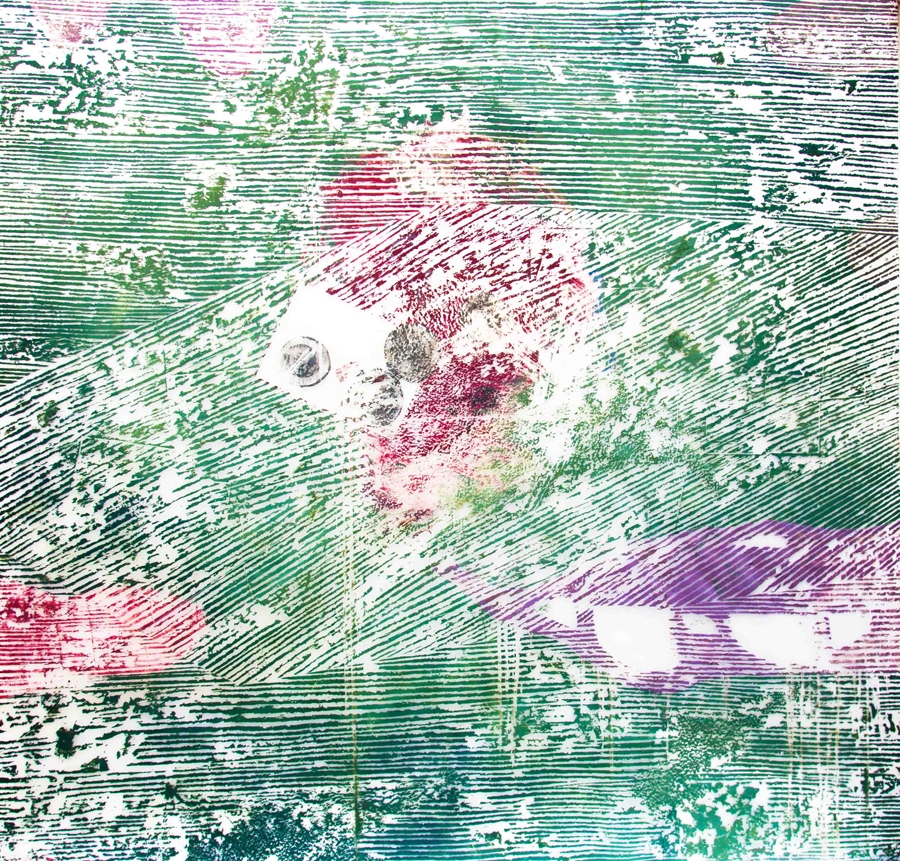

Multiple narratives and readings, as well as the approximate cartography of objects in space, are repeated thematically in the works in the basement, but the form is radically different. Paint lines left on transparent plastic film through a process of scratching away (as might be the case when creating the block for a woodcut print) reveal an abstract form and an obsession with materiality and process that eludes a clear concept – which is also a weakness of this body of work. In one of the rooms, two large-scale paintings of the aforementioned type might vaguely allude to landscapes, albeit ones so distorted that they collapse into pure abstraction. An installation in another darkened chamber combines the sound of a ventilator with the painted plastic film formed into a circular tunnel that invites you to walk through and wonder about the enigmatic lines and shapes you encounter. The artist’s stated aim of circumventing meaning, however, leads her into the realm of the purely aesthetic, which can be a trap if not balanced carefully. And yet there seems to be a search undertaken by Nistor to combine form and materiality with the arbitrary subjectivity of individual viewers, an approach that needs to be clarified conceptually a bit more to be successfully presented.

This article was first published in the December 2014 issue.