From Captain Tom and rainbow drawings to ‘Animal Crossing’ and Charli XCX, the pandemic has resurrected a spirit of wholesome self-improvement, even as society burns

One of the defining images of lockdown, at least in the UK, was that of Captain Tom Moore, diligently, perhaps even a little maniacally, completing laps of his garden to raise money for the National Health Service. As Moore took each step, doctors and nurses were fighting to save the lives of thousands of oxygen-starved COVID-19 patients. Over the course of three weeks, the 100-year-old army veteran went on to secure more than £32 million for the buckling health system, receiving a knighthood and, most recently, a bizarre chair upholstered in a replica World War 2 uniform for his efforts. First and foremost, the friendly-looking and do-gooding elderly man, stooped over his walking frame, was a slowly shuffling embodiment of wartime nostalgia; the Blitz spirit made real. But he was also, crucially, cute – certainly diminutive – and carrying out a task of almost-transcendent wholesomeness.

These two closely related albeit distinct aesthetic sensibilities – the cute and wholesome – seem to have grown ever more present during arguably the most disaster-stricken year in recent memory (and we’re yet to experience the full force of the impending economic crisis). Cultural theorist Sianne Ngai has written extensively on the former, referring to cuteness as a means of ‘aestheticizing powerlessness,’ objects imbued with this quality ‘appealing specifically to us for protection and care.’ In this scenario, however, Captain Tom is merely an extension of the now-cutified NHS; a world-leading health service transformed from a highly complex set of systems and services into a non-complex target of pity. There’s an obviously sadistic aspect to this metamorphosis instigated by a Conservative government which has arguably underfunded the NHS for a decade, yet seeks to capitalise on its populist fetishisation.

The cutification of the NHS is visible in the physical gestures which have haunted British streets throughout the pandemic. Crude but adorable rainbows painted by home-schooled children appeared as ghost-like apparitions in the windows of homes. In cities, at least, the daily clap for carers reverberated around densely populated concrete spaces, ringing in our ears as front-line workers tried to rest before heading back into the COVID-19 maelstrom (often without the correct protective equipment and at significant risk to their own families). These actions, alongside Captain Tom’s, however, hint at Ngai’s designation of ‘cute’ as both the site of a ‘static power differential’ and a ‘surprisingly complex power struggle’; we might treat the NHS as a cute object requiring our sympathy and care but this only reflects our own keenly felt vulnerabilities.

For many, video games have emerged as an embrace, and perhaps a surprisingly committed torchbearer for cute and wholesome aesthetics. Animal Crossing: New Horizons (2020) and Ooblets (2020) arrived in the last few months, two so-called ‘life simulators’ featuring cartoon visuals, anthropomorphic characters, and an array of wholesome tasks such as virtual friendship-making. In May, Wholesome Direct – an online event designed to plug the gap left by cancelled video game conferences – collected over 50 independent titles under the seemingly in-vogue banner. If we follow Ngai’s assertion that cuteness aestheticizes powerlessness, then these wholesome counterparts aestheticize self-improvement. This is palpable in Animal Crossing and Ooblets, both of which, alongside outwardly cheerful dispositions, offer a set of interactions to roleplay kindness and consideration. These opportunities for betterment resonate with booming real-world pastimes such as breadmaking; at the height of lockdown, fledgling bakers emptied supermarkets of flour, keen to both learn a new skill and fill their guts with healthy (not to mention cute!) microbacteria.

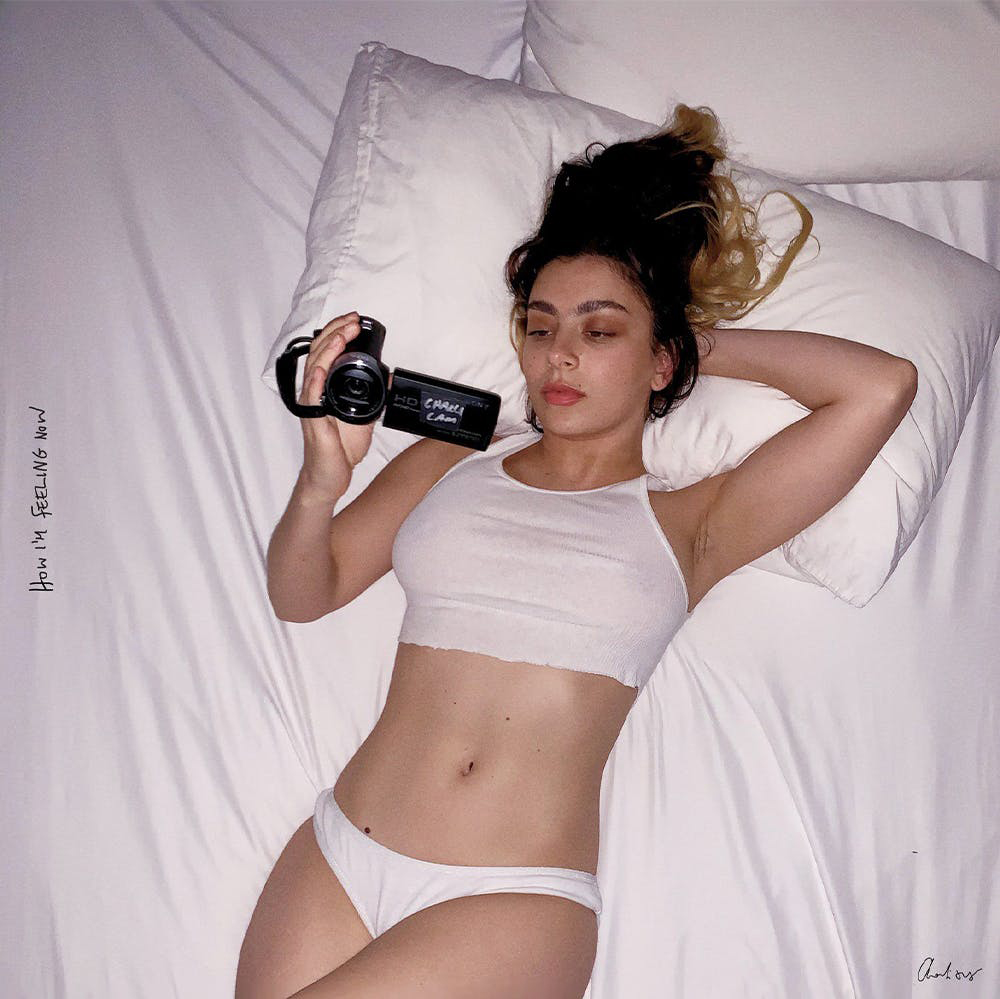

The purest, and most life-affirming, crystallisation of these cute and wholesome aesthetics arrived via pop artist Charli XCX’s How I’m Feeling Now (2020), an album recorded entirely during lockdown in dialogue with her fans on social media. The record’s intimacy is reflected precisely in its music videos; for the ‘forever’ promo – a heartfelt pop ballad directed towards her boyfriend Huck Kwong – the British star asked fans to send in their own camera phone footage responding to prompts such as ‘your favourite party you want to remember forever.’ Rapid-fire cuts of everyday spaces and often cute objects (including cuddly toys) are juxtaposed with images of the singer herself. Charli XCX effectively and self-knowingly transformed herself into an object of cuteness; her hypertextual pop songs were an exercise in lockdown self-improvement; and she deftly captured the everyday qualities of this disaster like no one else.

At their best, these two affable aesthetics – the cute and wholesome – afford us the space to transcend an often bleak-feeling everyday. But there’s an inverse, and arguably an impotency to such ostensibly nourishing outlooks. The cute transforms us (and our objects of attention) into both literal and metaphorical vessels of babbling baby-speak, perhaps fatally so in a time when critical facilities are more important than ever. The wholesome, in contrast, is concerned with a different lockdown transformation. It speaks, possibly fundamentally, to a wider belief in the potential for simple, unassuming tasks to make better citizens of us all (and maybe the world). We busy ourselves with these activities, art, and mundane adventures, all while the very fabric of society is being shredded before our eyes.

Lewis Gordon is a UK-based writer on technology and culture. His writing has appeared in Vice, The Verge and The Nation, among others.