ArtReview sent a questionnaire to artists and curators exhibiting in and curating the various national pavilions of the 2024 Venice Biennale, the responses to which will be published daily in the leadup to and during the Venice Biennale, which runs from 20 April – 24 November.

Eva Koťátková in collaboration with curator Hana Janečková, artists Himali Singh Soin and David Soin Tappeser (who form the collective Hylozoic/Desires), the artists and researchers’ collective Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures, as well as groups of children and older people, are representing the Czech Republic; the Czech Pavilion is located in the Giardini.

ArtReview What do you think of when you think of Venice?

Hana Janečková As a sea lover living in a landlocked country: of course canals, the sea and incredible sunsets from the Giardini gardens, but also tourists, cruise ships and environmental damage.

Eva Koťátková Water and water systems – since the project brought us to study different hidden systems under the surface, out of sight – sewage systems as well as other things that we do not see or that we intentionally overlook.

AR What can you tell us about your exhibition plans for Venice?

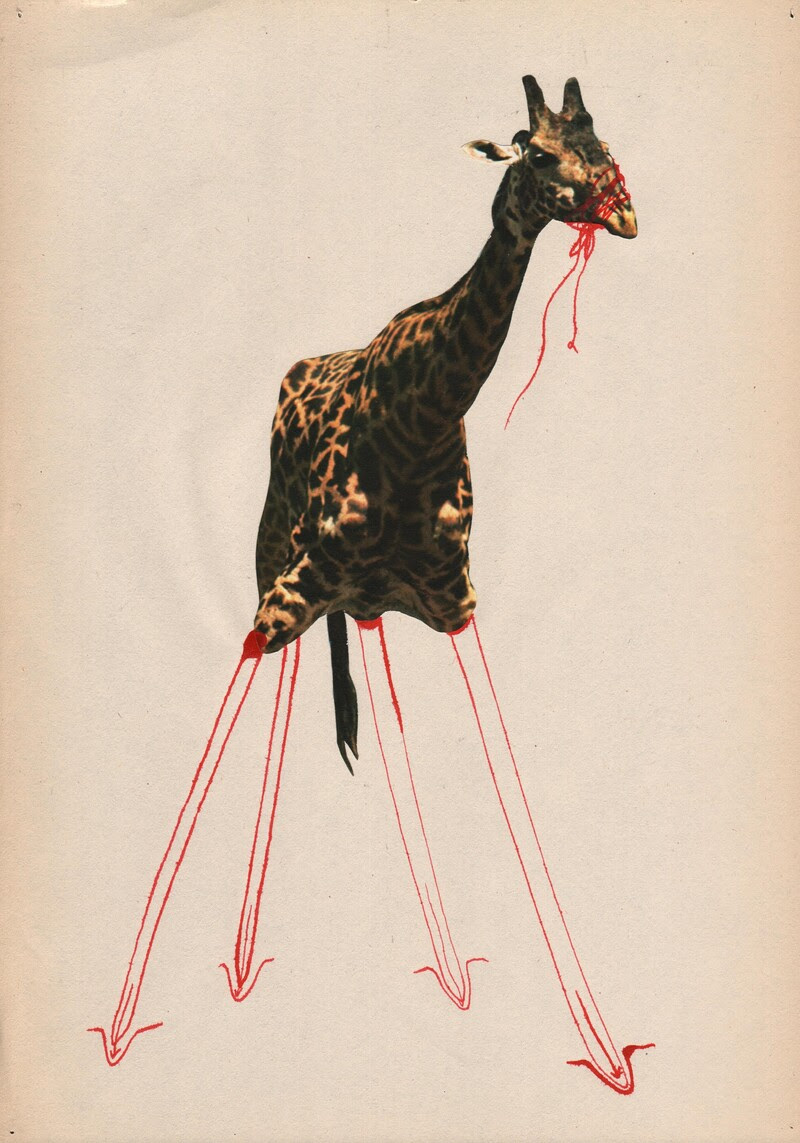

EK & HJ The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter is a collaborative project which tells the story of Lenka the giraffe who was captured in Kenya in 1954 and transported to Prague Zoo to become the very first Czechoslovak giraffe. She survived only two years in captivity, after which her body was donated to the National Museum in Prague where it was exhibited until 2000. The artefact Lenka is currently held in the museum’s research archive, as an object of science deemed to an endless life. In the immersive installation and performance Lenka’s story will be staged as a poetic, embodied encounter for the audience, invited collaborators and the artist. But it is also a place of critical intervention in the relationship between institutions and the natural world as it builds on the histories of the Czechoslovak animal acquisition from the countries of the Global South.

AR Why is the Venice Biennale still important, if at all? And what is the importance of showing there? Is it about visibility, inclusion, acknowledgement?

EK & HJ For us it has been an incredible opportunity to work together on a project that we believe is really important and that deserves the visibility and acknowledgement, as you mention, that the Venice Biennale offers. For us it makes sense if it can provide a space to interrogate its own premise – eurocentrism, single artist’s presentation and narrowly defined categories of nationhood. The project’s collaborative and open framework is incredibly important to us – the project has emerged in a close collaboration between us but it was important that our invitation be extended to Himali [Singh Soin] and David [Soin Tappeser], GTDF [Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures], and we’ve also had the opportunity to involve groups of children, educators and older people to respond to the story.

In this respect it seems to us that the Venice Biennale has its relevance as a platform to probe questions such as what constitutes ‘national’ representation – which this year’s theme by Adriano Pedrosa, Foreigners Everywhere, addresses. One of the most important questions of The heart of a giraffe… is in what way belonging can be formed and how it can happen through emotional attachment, reparation and ecological relations instead of fixed notions of identity, borders and nation.

AR When you make artworks do you have a specific audience in mind?

EK On the contrary, I try to create landscapes for as diverse groups as possible. I like to think about my exhibitions as temporarily composed collective bodies that inhabit a certain space and form themselves into a shape that does not depend only on my input but also on what people bring in it – what stories they are willing to share, what interactions they choose etc. But it is true that I also tend to think, when making an exhibition or other public formats, more and more about those for whom the access to an exhibition space is not that easy if not impossible in their current situation, and come up with ways to change it.

AR Do you think there is such a thing as national art? Or is all art universal? Is there something that defines your nation’s artistic traditions? And what is misunderstood or forgotten about your nation’s art history?

EK & HJ This might be a contentious thing to say but we believe the term national art used to be a useful category in certain parts of Czech history, but we have to be extremely careful with it at the present. Saying this – to claim that art is universal – can be also problematic. For us it is important to understand art as situated – coming from a specific set of experiences, contexts and histories, which are bound together by interconnected networks and material relations.

For our project it is relevant that the Czech Republic has a complicated relationship to colonialism: having been occupied by the Soviet Union, Germany, the Austrian Hungarian Empire, it is sometimes difficult for the Czech people to relate to ‘Western’ concepts such as decoloniality. Yet it is very important that questions of complicity in the colonial project are asked, but they should be asked in terms that take the complexities of Central European contexts into account. We see possibilities of contemporary art to open these questions through different modes of engagement to established narratives and histories.

AR If someone were to visit your nation, what three things would you recommend they see or read in order to understand it better?

HJ While this might be a cliché, I think novels by Franz Kafka, who was Czech, Jewish but also German, summarise very aptly a certain sensibility of being Central European, but it also shows the enduring importance of his work. For example, the persecution that some Jewish artists and intellectuals must endure for not supporting Zionism at the present could be easily a part of the bureaucratic panopticon Kafka described a hundred years ago.EK I often think about his short story called The Burrow that describes a complicated labyrinthic system of underground corridors that an unknown being had built as a burrow for itself and a trap for others. The Burrow is very precise in how it speaks about systems we live in and systems we build ourselves to survive in the bigger systems: “I have left the upper world and am in my burrow and I feel its effect at once. It is a new world, endowing me with new powers, and what I felt as fatigue up there is no longer that here….”

AR Which other artists have influenced or inspired you?

EK It is especially artists that combine personal experience with political stands and pedagogical involvement. Two years ago Cecilia Vicuña was awarded a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale. She is exactly that type of artist I deeply admire and respect and who gives me hope that through art we can actively shape the world we live in for the better. Also, I come from the Czech Republic with a small, yet very strong artistic scene, with so many unique and inspirational emerging positions that are deserving of more international attention.

HJ There are so many artists I deeply admire, many of which are my friends and colleagues from the Czech Republic but also from the UK where I was based for a very long time. Recently I’ve been looking intensely into Amanda Boulos’s paintings of the war from 2017–18 for their deeply unsettling, predictive nature.

AR What, other than your own work, are you looking forward to seeing while you are in Venice?

EK & HJ To be honest, we have been incredibly busy in the last few months to pursue other projects but I’ve heard some news about the project of the Dutch Pavilion, which sounds incredibly exciting; also the Finnish Pavilion has some of our favourite artists involved. We are incredibly excited about the main exhibition, Foreigners Everywhere, especially at this very difficult time we live in. Of course we are also looking forward to a presentation by our acquaintances and friends such as Oto Hudec who represents the Slovak Republic, the Catalan Pavilion curated by Filipa Ramos, Croatian Pavilion, Lithuanian Pavilion and many others.

The 60th Venice Biennale, 20 April – 24 November