‘From now on if you only do this work, I promise you that in two years you’ll be the greatest newspaper gluer of all time.’ Advice (or was it an order?) given by legendary dealer Ileana Sonnabend during a 1972 meeting with a young Gianfranco Baruchello, then making sculptures composed of newspaper, wire wool, radio circuits and other objects fixed to painted board. Vexed by Sonnabend’s cynicism, the Italian replied in a flash: ‘I’m sorry but I’m done. Now I want to do something else!’

True to his word, Baruchello – now aged ninety-one – has consistently eschewed the traditional means of visual art, establishing a reputation based on the diversity of his interests and outputs. There have been various philosophical excursions, including the 22-hour-long video Starting from the Sweet (1979), which drew thinkers such as Jean-François Lyotard, Félix Guattari and Paul Virilio into collaboration; the founding of a limited company called Artiflex, its humble aim to ‘commodify everything’; and the project that perhaps best shows off Baruchello’s experimental largesse, Agricola Cornelia S.P.A. (1973–81), a pioneering example of that high counterculture trope, the art farm.

However, Baruchello’s practice does have its constants. Somewhat ironically, around the time he was conversing with Sonnabend, he began a series of paintings that, in form and general approach, continues today. Indeed, contra to titular suggestion, the ‘new works’ in this exhibition, their all-white surfaces populated by a ‘universe’ of small images and symbols, actually suggest an unbroken continuum in Baruchello’s art, one that goes back more than 50 years.

Occupying the ground floor of Massimo De Carlo’s Mayfair gallery are five equilateral aluminium canvases – all titled La Formula (2013/14). Just about apparent in the superficial blankness of each canvas is a filigree of precise, brightly coloured depictions. Allusions are made to the order of the natural world: bugs, leaves, flowers, cocks and balls are set into schematic relation through a host of lines and interconnecting frames. Beyond that, it’s not particularly clear what is being illustrated.

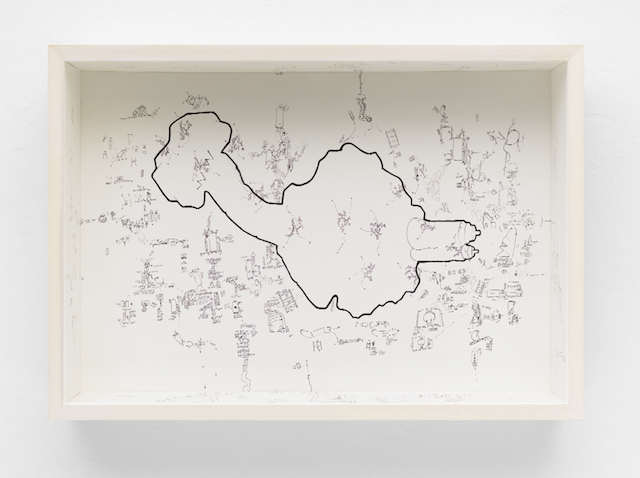

Downstairs, things carry on in a similar manner. Instead of covering aluminium, Baruchello’s cryptic webs sprawl over routed, whitewashed wood shapes or cover cardboard and Plexiglas set inside deep, wall-mounted display boxes. Any colour present in the works upstairs has drained. Things get moodier and weirder. Murmur (2015) – a double-head-shaped object displaying an impenetrable matrix of black stoner-doodles – sets the tone, like the box-frames also present, cultivating a fuggy, neurotic feel for the lower gallery.

Though exploiting a certain instructive visual language, the overall effect of Baruchello’s painting remains disorientating. It’s tempting to suggest that the drive to interpret these works as being representative of x or y is the particular Holzweg to be avoided here. Perhaps this way of working has remained central to Baruchello’s practice for so long precisely because it resists the good path towards certitude, allowing his complex imagination much-needed room to stretch and breathe.

This article was first published in the January & February 2016 issue of ArtReview.