Ashadu’s films attempt a ruminative portrayal of men and what might traditionally be considered male-dominated spaces in Nigeria

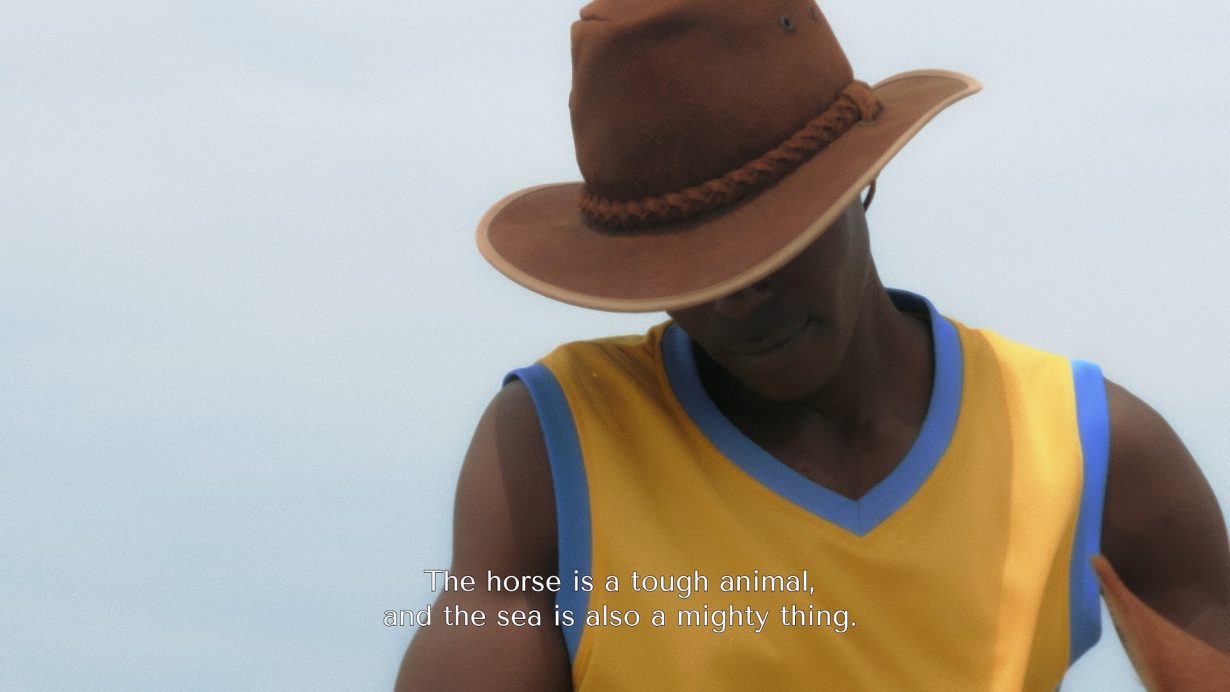

We see the cowboy as he lifts himself atop the horse. His movement is practiced and assured. Once he gets going and the animal picks up speed, they cross a puddle and make their way through a winding path. They come to a clearing, and just ahead, there is a hint of sea. They gallop into a rush of waves, as though wishing to go further. The cowboy reins the horse with a sudden pull when it is ankle deep in water, the abrupt climax of a thrilling sequence observing a man in physical dialogue with another animal.

This illuminating moment in Karimah Ashadu’s Cowboy (2022) is one of many in three films that take as particular renderings of life in Lagos as their purview. Her latest, MUSCLE (2025), is a close look at body builders in a Lagos suburb; Cowboy tells a story of a man’s dedication to horses; and King of Boys (Abattoir of Makoko) (2015) focuses on the mundanities of a street where an abattoir is located. Ashadu, born in the UK and raised in Nigeria until she was ten years old, is now based in Lagos and Hamburg, and has produced films, for the most part, that examine the inner workings of Nigerian communities.

It is apparent, almost at once, that these films attempt a ruminative portrayal of men and what might traditionally be considered male-dominated spaces in Nigeria – a place where ‘maleness’ is often defined by the kind of work or lifestyle a person chooses to do or live. This attentiveness feels most expansive in MUSCLE, in which close-ups of bodybuilders – and the rhythmic and arhythmic (often eroticised) sounds they make while pushing their bodies to the limit – signals the filmmaker’s maximalist approach to looking at men. Yet the impulse is there in the earlier work King of Boys, albeit in a more subtle form, where the action of hacking at the carcasses of cows, lifting it or bantering around it, is the preserve of boys and men, who are mostly seen in the frame doing the work. In the two-channel Cowboy – to my mind the most accomplished film in the exhibition because of its sustained attention on a single individual – the notion of maleness is quieter: set against a wider narrative beyond the province of masculinity, it is shown in the form of an intimate connection between a man and a beast. The film, which is comprised of slow shots of the cowboy tending to his horse and accompanied by the protagonist’s voiceover, documents the life of a man from northern Nigeria who considers horses kin.

Ashadu’s films are often nonlinear, with little attention paid to chronology. In her poetic stitching together of footage for each film, she casts a gaze over the all-pervasive culture of patriarchy – and what results is an unflinching vision, expressed via a scrupulously long, slow look at men, ultimately framing them as equal and, simply, human. Yet, there is another kind of visual investigation to be taken into account. All three films make an abstraction of communities or persons in Nigeria. That abstraction could be reasonably described as a ‘sensory ethnography’, a research methodology that denotes an innovative combination of aesthetics and anthropology. In Ashadu’s work this is achieved mainly through her tight framing of bodies and landscape. As in every type of ethnography, however, the films are sited in the exotic.

The male bodies in MUSCLE – filmed while their biceps bulge, eyes flare, arms stiffen – are seen in such proximity it is nearly impossible to consider them except as essentialised. While Ashadu’s films do not register as extractivist, the filmmaker also seems to establish a sense of distance between herself and the subjects within her frame. I got the feeling, while watching the films, that her interests lie less in examining why she has chosen these so-called everyday sites and subjects, and more in creating beautifully sequenced close-up shots of them. To make a semantic point, the proximity is sympathetic but scarcely empathetic. Watching King of Boys, for instance, filmed without a narrative voiceover, I felt at a loss as to why Ashadu had chosen to pan her camera across the normal course of activity in a Lagos slum. Perhaps it all comes down to her diasporic eye, of relating with Nigeria from the position of one who occasionally visits. And, without sounding reductive, showing these films in a London gallery and other Western venues could be precisely how the work is meant to be seen – as detached engagements with the intricacies of Nigerian life.

Despite this, the careful suturing of the voiceovers in Cowboy and MUSCLE reveal a complexity in the male psyche. There is some vulnerability – a tenderness – implied in what is said about their endeavours. One such example is found in the entrancing, exhortative cadence of the cowboy’s voice, who, towards the end of the film, as he rides out to sea, says in Hausa: ‘When the rider drives the horse to the sea, he goes with a clear mind. The horse does not turn back. It is the rider who has to rein in his conscience.’ Or when a bodybuilder says, ‘I can die weight lifting.’ However few, these testimonials of male conscientiousness are rewarding moments in Ashadu’s sensorial investment in the flow of life.

Tendered at Camden Art Centre, London, through 22 March 2026