In partnership with Sharjah Architectural Triennial, ArtReview publishes three new essays exploring sites of environmental struggle and models of social organisation. The essays are authored by participants in the inaugural triennial (9 November 2019 – 8 February 2020) and commissioned as part of the Rights of Future Generations: Conditions programme. The complete set of texts can be accessed on the triennial’s website and will be available as a print book from November.

There is no such thing as dry land. Wetness is everywhere to some degree. It is in the seas, clouds, rain, dew, air, soil, minerals, plants, animals. The sea is very wet; the desert less so.So, when we experience ‘water’ on the other side of a line that allegedly separates it from ‘land’, we know it to be by design, design that articulates a surface for habitation. This surface has served as a ground for experience, understanding and knowledge. Today, however, with rising seas, warming temperatures, and the increasing frequency of floods, this surface along with the edifice of civilization and certainty built upon it is threatened, calling into question the act of separation that brought it into being.

— Anuradha Mathur, Dilip Da Cunha

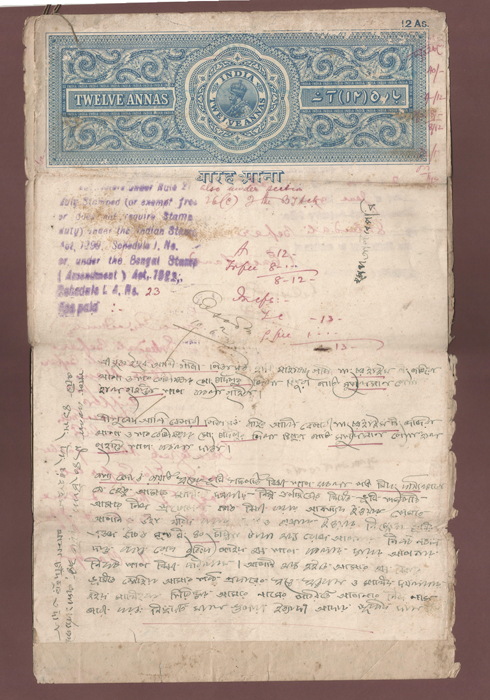

‘Wetness’ defines the Ganges Delta better than any assumptions of what ‘land’ is. At the confluence of the Padma, Meghna and Jamuna Rivers, in the south of Bangladesh, the riverbed – on which humans tread, draw lines to mark territory, build their dreams and pass them on to future generations – is, essentially, wet. From one day to the next, a parcel of ‘land’ disappears, dissolving into the river. Its inhabitants move on to the next patch of solid ground, carrying their belongings, memories, and, most important, their desire to return to the vanished land. Land deeds, documents and maps are carefully locked away.

From one day to the next, a parcel of ‘land’ disappears, dissolving into the river… The land may resurface in one, two, or three generations

It’s a long wait; no one knows how long. It may be ten or twenty or thirty years, or even longer. The land may resurface in one, two, or three generations. The inhabitants keep their memories alive with stories, while adjusting to their new life. These stories pass on from father to son to grandson, while the bundles of paper documents are forgotten in a drawer.

During dry seasons, water subsides and land generated by accretion can emerge. Fishermen and boatmen are the first to know about this new land, which is locally known as char. Every time a new char appears, the word spreads fast around the mainland. The alluvium of the delta is fertile ground. If a char is not eroded for the first four years of its existence, it can then be used for either cultivation or settlement. These possibilities encourage landless families and river nomads, those who are locally called Charua, to migrate to the newly emerged land. Furthermore, the Meghna estuary is abundant with the hilsa fish that migrate upstream for spawning; they are among the most popular and sought-after fish of the Indian subcontinent.

While different people fight over ownership, nature silently steps in with tall grass (hogol) that anchors the soil. Mudskipper fish are the first to appear, attracting the birds. Crabs and shellfish colonies emerge from the riverbed. While fishermen start to stake boundaries (ghers) around the char, buffalos are brought in for grazing. The Charua can also make a living by taking care of the livestock.

In the settlement of Haimchar in the Lower Meghna, a new char recently surfaced in the place where a riverbank eroded in 2002. Shafiul Azam Shamim, a thirty-two-year-old architect living and practicing in Dhaka, can still recall his grandparents’ homestead that washed away with the riverbank when the char formed: a two-bedroom cluster with a kitchen and toilet, all arranged around a courtyard. He often visited them as a child. “This is the same house,” he says, standing in the courtyard of the new homestead. “Nothing has changed except the location. These two buildings have survived three erosions. This is the third site where the houses have been re-erected.” Haimchar is full of such stories of households displaced and relocated. The local village doctor, Nazrul Islam, inherited his grandfather’s house, which is sixty years old. Over the past six decades, it moved to seven different locations.

The Ganges Delta is a dynamic water system, a continuous interplay of erosion and accretion – a unique phenomenon that has long shaped the lives of Bengalis dwelling in this fragile region

The transient nature of the chars of Bangladesh can be best described as a by-product of the enormous Himalayan water flows. The Ganges Delta is a dynamic water system, a continuous interplay of erosion and accretion – a unique phenomenon that has long shaped the lives of Bengalis dwelling in this fragile region. The water level rises during the monsoon season, between June and October. The tributary streams carry excess water from the Himalayas, and the intensity of tidal waves increases erosion of the riverbanks. Tidal action plays a key role in the sedimentation process, as well as in forming and shaping the deltas. The Ganges Delta in its present form covers an area of 105,000 square kilometres. Every year, the rivers carry approximately one billion tons of sediment, extending the coastline seaward. Yet it is receding differently from most other deltas in the world: over the past five decades, the Ganges Delta has been advancing at a rate of 17 square kilometres each year. This process, called progradation, makes the river system highly unstable.(1) There exists a duality of joy and untold torment for the large number of people living along the banks of the streams of Bangladesh.

Shamim’s grandfather, Mohammad Imam Hossain Bepari, is now eighty-three years old. His neighbours are busy meeting Khokon Bepari, the local amin. An amin is a land surveyor or arbitrator hired by the government to survey, record, and assess land ownership. During the Mughal period, amins were responsible for collecting revenue. They remain the most knowledgeable and trusted sources in matters concerning the legal aspects of landownership.

Village elders can recall their homesteads by referencing trees and other features in the neighbouring properties that were not washed away. Shamim’s aunt, Khurshida Begum, who is sixty-five, continues to live on her property at the edge of the Meghna River. Her homestead survived the last period of erosion. Her family was prepared to move, but the river was kind enough to spare them. Now, her house has become the reference for others who are claiming their properties in the newly emerged char. It’s time for the bundle of land deeds to be taken out of the drawers. Through a couple of meetings with the amin and visits to the resurfaced char, ownership boundaries are settled based on old survey drawings, which are locally known as mouza maps.

The history of cadastral subdivisions (mouza), themselves, goes back to the Sultanate period (thirteenth–sixteenth centuries), but written documentation of landownership was commenced only in 1888. Following the enactment of the Bengal Tenancy Act of 1885, the British Empire introduced a modern cadastral survey in order to facilitate revenue collection. The survey was completed in 1940, and revised only twice after that. Today, the mouza maps are still the only landownership documents that the Land Department of Bangladesh acknowledges as official.

Under the British Empire, the practices of a dry culture, which marked the limits of rivers with lines, was imposed on the wet culture of the Bengal delta

This means that any new chars that have surfaced since they were last updated have remained undocumented. When undocumented, such land becomes the property of the government, and is known as khas land. These areas are generally occupied by landless people and river nomads. However, there have been numerous incidents of land-grabbing by Jotedars, the wealthy peasants and landowners. In the absence of formal recognition, landless families can fall victim to the trickery of the Jotedars, who use false documents to trade the khas land upon which they live.

Under the British Empire, marshlands began to be consolidated and fortified into riverbanks, so that they could become recognisable geographical formations. The first survey of the river system was conducted by the Territories Department of the East India Company in 1820, in order to ascertain the company’s property claims. The subsequent acquisition process targeted all those lands that were either unclaimed or for which inhabitants were unable to produce a recognisable land title. As Debjani Bhattacharyya writes, ‘merchants of a joint stock company turned themselves into landlords and laid the “legal” groundwork for land acquisition in the colony.’(2) The legal notion of a boundary between land and water was thus established. The practices of a dry culture, which marked the limits of rivers with lines, was imposed on the wet culture of the Bengal delta; the latter had been accustomed to adapting to and negotiating with the ways of the water.

What compels people to live in such a difficult terrain? Why don’t they move to more stable ground? “It is home. This is where our near and dear ones live and come back to,” Shafiul’s grandfather says. Yet, talking to local inhabitants also reveals the economic struggles behind the feelings of home, which are rooted in the natural richness of the delta ecology.

Can such wetness be treated as land? Can the legal concept of land apply to these transitory grounds? Can wetness be passed on to future generations through the language of landownership? The rise in sea level induced by anthropogenic climate change will make the Ganges Delta considerably more vulnerable in the coming decades. These are urgent questions that need to be asked in a time of increased uncertainty and when adaptation to instability might well be the only strategy left.

***

(1) Jakia Akter, Maminul Haque Sarker, Ioana Popescu and Dano Roelvink, “Evolution of the Bengal Delta and Its Prevailing Processes”, Journal of Coastal Research 32, no. 5 (2016), 1212–26

(2) Debjani Bhattacharyya, “Manufactured Landscape: Law and Hydraulics in the Bengal Delta”, Technology’s Stories, June 21, 2016 (last accessed August 28, 2019)

***

Marina Tabassum is a Dhaka-based architect. In 2016, she was the recipient of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture